COVID-19 and Canada’s Underutilized Internationally Educated Health Professionals

Joan Atlin, Associate Director, Strategy, Policy, and Research, WES

There is growing evidence of the disproportionate negative economic and health impacts of COVID-19 on immigrant, low-income Canadian women of colour. Many of these Canadians are frontline, essential workers in Canada’s health care sector.

According to the 2016 census, fully a third of the nurse aides, orderlies, and patient service associates in Canada are immigrants, and 86 percent are women. The frontline workforce in the long-term care (LTC) sector in particular is largely made up of immigrant, female, visible minorities: 86 percent of workers in nursing homes and 89 percent in home care are women. “Racialized” women make up 33 percent of nurse aides, orderlies, and patient service associates, and 38 percent of home support workers, housekeepers, and related occupations. These workers are therefore particularly vulnerable, given the high rates of COVID-19 infection among both long-term care residents and those who care for them. The Canadian Institute for Health Information reports that nearly 20 percent of all those who tested positive for the coronavirus in Canada as of late July were health care workers.

At the same time, there are large numbers of internationally educated health professionals (IEHPs) in Canada who are licensed to practice in other countries, and many wish to be mobilized to support Canada’s COVID-19 response. In March 2020, internationally educated doctors Ayesha Mohammad and Ali Mahdi launched a petition on Change.org. In a matter of weeks, the petition had garnered nearly 35,000 signatures. It reads, in part:

“We are a significant community of international medical graduates in Canada who are ready and well prepared to work in the Canadian medical field. Many of us have worked in different medical specialties for years, and most of us are going through the examination process.… Given the prevailing and unprecedented circumstances at the heart of the global emergency posed by the coronavirus outbreak, we are coming forward to willingly volunteer, hands-on, without expectation of pay, so we can alleviate frontline workers during this time of crisis.”

The Change.org petition caught the attention of Canada’s media. Stories of IEHPs, both those working in and those stuck on the outside of Canada’s health and LTC systems, are once again on the public’s radar. The pandemic has led not only to a call from IEHPs to be fully engaged in contributing their skills, but also to an opportunity to reopen a conversation that has largely stalled in Canada in recent years: how to ensure that IEHPs have equitable access to licensure pathways so that the country does not underutilize IEHP skills and experience which could be contributing to our health care system.

The Numbers: Canada’s Underutilized IEHPs

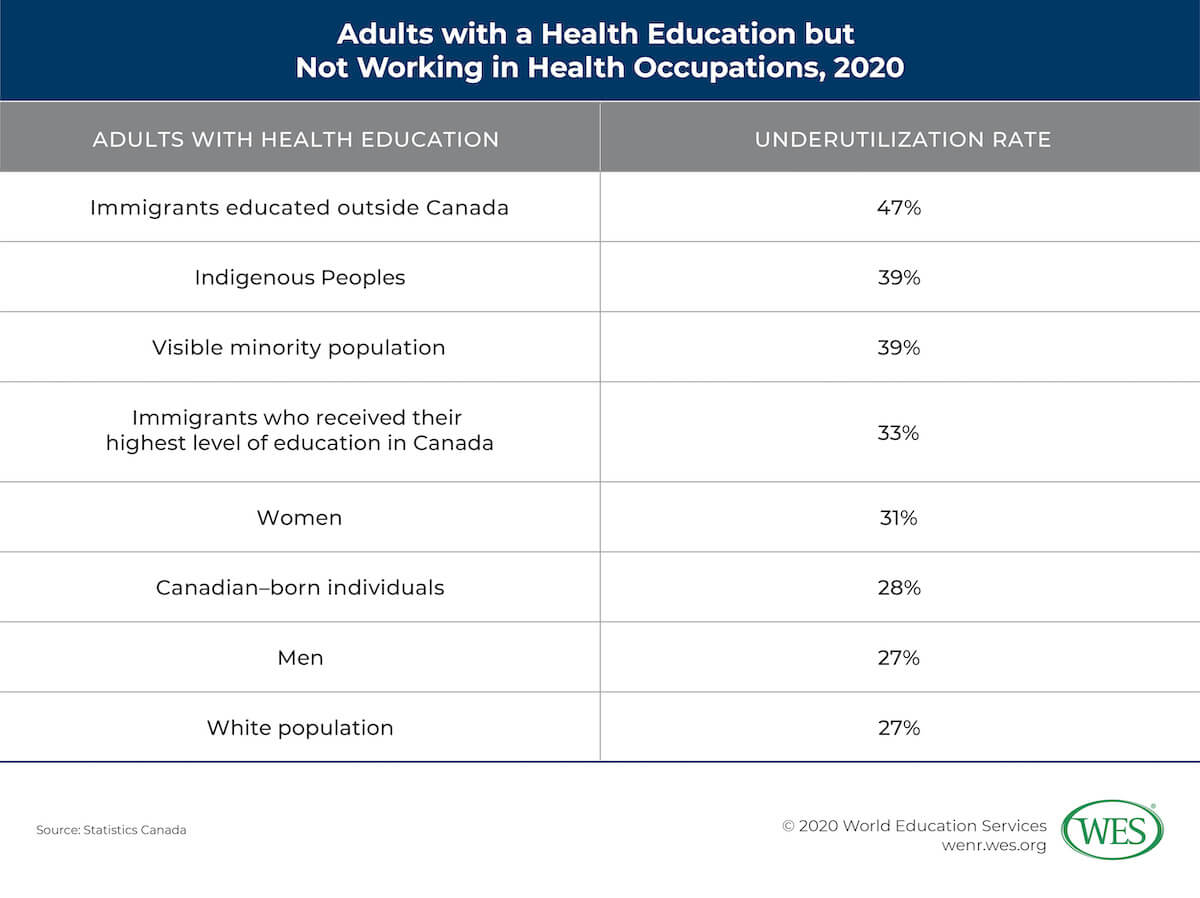

The numbers tell a clear story of a large and vastly underemployed IEHP workforce in Canada. In April 2020, Statistics Canada published a new study in its COVID-19 series: Adults with a Health Education but Not Working in Health Occupations. Using 2016 census data for people age 20 to 44, the study looks at the underutilization of individuals in Canada who have health education: the Canadian-born, immigrants who received their highest level of education in Canada, and immigrants who received their health education abroad. The study defines “underutilization” as “people with postsecondary education in a health-related field who are not employed or work in non-health occupations that require no more than a high school diploma.” According to the report, in the third quarter of 2019, about 40,000 health care jobs in Canada were unfilled. More than half of these positions were assistant level and technical jobs—essential roles in the fight against the pandemic. Another 30 percent were in nursing.

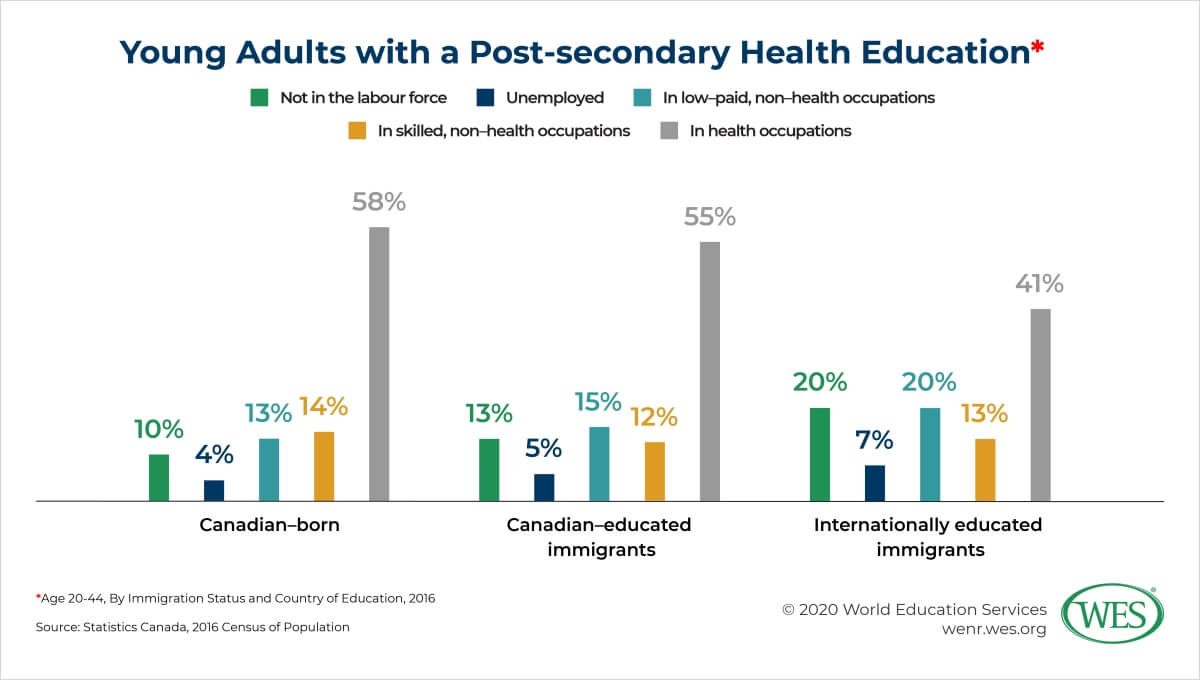

However, the report shows that only 41 percent of immigrants educated abroad are working in health occupations, compared with 58 percent of Canadian-born individuals with a health education, and 55 percent of Canadian-educated immigrants. Nearly half (47 percent) of immigrants who received their health education abroad are underutilized. The statistics indicate higher rates of underutilization among women versus men, and among visible minorities in comparison to White populations.

This intersectionality is reflected in the fact that among immigrants educated abroad, underutilization rates were highest in nursing (34 percent), a largely feminized workforce, followed by medicine (12 percent), and pharmacy (8 percent). A June 2020 Statistics Canada report shows that in the census metropolitan areas of Toronto, Vancouver, and Calgary, more than 70 percent of nurse aides, orderlies, and patient service associates were immigrants, and over 80 percent of these immigrant workers were women. Across Canada, 25 percent of immigrants in these occupations held at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with only 5 percent of non-immigrants; 44 percent of immigrant workers had a degree in a health-related field compared with 22 percent of non-immigrants. Of the immigrant workers with a health-related degree, fully 69 percent held a degree in nursing.

Initiatives to Open Up Access

The issue of underutilization and barriers to access that deter IEHPs and other immigrants in regulated professions is long-standing and well documented. As far back as 1988, the Ontario government appointed a Task Force on Access to Professions and Trades that issued the groundbreaking “Access!” report. Yet it wasn’t until the early 2000s, owing to a combination of effective advocacy both inside and outside government, and concerns about personnel shortages in the health care system, that a moment of political will emerged and a range of IEHP initiatives were undertaken across the country.

In 2002, Health Canada convened the Canadian Task Force on Licensure of International Medical Graduates (IMGs)—a term which comprises both immigrant physicians already licensed in other countries and Canadians who travel abroad to obtain a medical degree. The Task Force brought together the complex array of federal and provincial licensing and medical education players to identify challenges and recommend solutions. The number of spaces in medical residency programs designated for IMGs in Ontario, for instance, increased from only 15 to about 200, which is roughly where it remains today, despite increasing numbers of returning Canadians who studied medicine abroad also competing for and winning these limited spots.

Around this time, bridging programs were developed to support nurses, pharmacists, medical lab technicians, midwives, and others to pursue licensure. The programs provide occupation-specific language training, gap training or academic upgrading where required, exposure and orientation to the Canadian workplace, support in preparing for licensure exams, and support in entering the labour market. World Education Services (WES) opened its Ontario office in 2000 to establish academic equivalency assessment services in Canada. Loan programs were developed to help IEHPs pay for licensure exams, bridging programs, and other associated expenses. And in 2006, Ontario passed the Fair Access to Regulated Professions Act and established the Office of the Fairness Commissioner. Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and Quebec followed suit in 2008 and 2009, and Alberta recently created a similar structure.

While these interventions have had a demonstrably positive impact and helped significant numbers of IEHPs practice professionally in Canada, the Statistics Canada report clearly shows that the problem is far from solved. The personal and societal costs of underutilization are paid not only by IEHPs and their families, but also by our health care system, our economy, and our society. We continue to have thousands of IEHPs sitting on the sidelines, unemployed or working in jobs that do not leverage their education, skills, and experience. Many of them, given adequate access to assessment and bridging opportunities, would be able to demonstrate their ability to meet justifiably rigorous Canadian standards.

Can the COVID-19 Crisis Open New Ways Forward?

In March 2020, WES, the Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants (OCASI), and the Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council (TRIEC) jointly responded to the Ontario government’s call for ideas to fight the virus. The proposal was a call to action to bring together key stakeholders to develop a plan that would mobilize Ontario’s IEHPs as part of the response. At that time, the province was preparing for the kind of surge that Italy and nearby New York state were experiencing. Ontario and other provinces initially focused on encouraging retired and out-of-service professionals to register on government and professional recruitment portals in anticipation of extreme personnel shortages in hospitals. After some initial challenges, the Ontario government portal was adjusted to allow IEHPs to indicate their professional health care background as well.

While the surge of cases in the first wave of the pandemic in Canada did not overwhelm our hospitals, the coronavirus spread with tragic consequences in long-term care facilities, particularly in Ontario and Quebec. LTC facilities continue to be under unprecedented strain. Hundreds of these homes across the country have dealt with outbreaks, large numbers of deaths, and extreme shortages of both personal support workers and nursing and medical personnel. In April, in response to urgent requests for help, the federal government took the extraordinary step of deploying the Canadian Armed Forces to offer short-term support to some LTC homes in Ontario and Quebec. In Ontario, many hospitals were paired with LTC homes to support infection control and help manage outbreaks.

The calls for major reform of Canada’s LTC system are coinciding with renewed appeals to address the ongoing structural issues that prevent so many of Canada’s IEHPs from putting their skills, education, and experience to work here. WES and our partners are exploring ways to leverage this synergy. Much like the early 2000s, this is a moment when renewed political will can create new opportunities for innovative partnerships and solutions to bring Canada’s vastly underutilized, highly skilled IEHPs into the mainstream of our health care system. This is the time to re-ignite a national conversation about advancing systemic changes that will enable more IEHPs to acquire licensure and enter the health care workforce—where they want to be, and where Canada needs them.

A version of this article first appeared in Canadian Diversity.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).