Education in South Korea

Deepti Mani, Research Associate, WES, and Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

This education profile describes recent trends in South Korean education and student mobility and provides an overview of the structure of the education system of South Korea. It replaces an earlier version by Hanna Park and Nick Clark.

Introduction: The Priority of Education in the World’s Most Educated Society

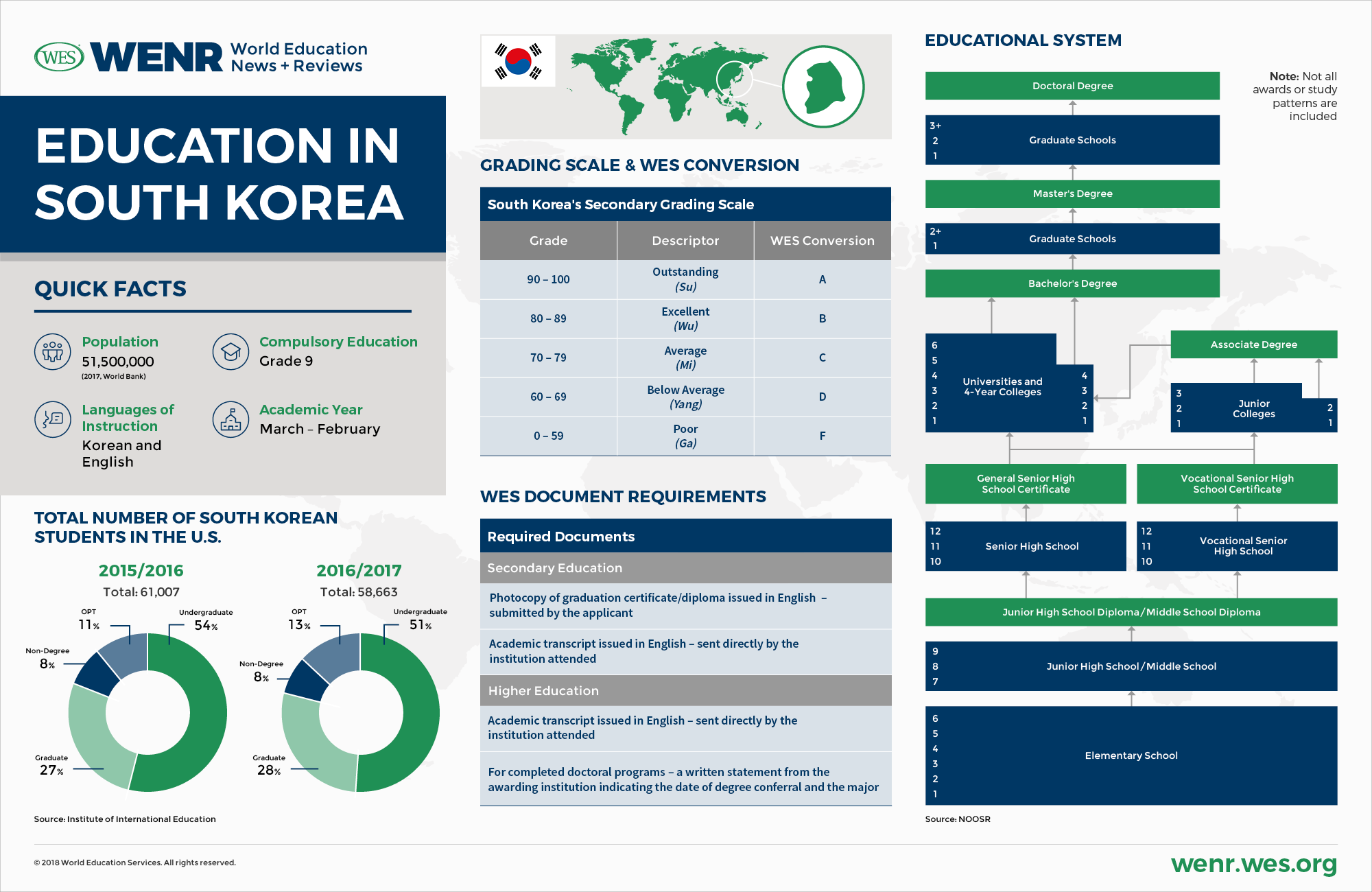

By some measures, South Korea—the Republic of Korea—is the most educated country in the world. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 70 percent of 24- to 35-year-olds in the nation of 51.5 million people have completed some form of tertiary education—the highest percentage worldwide and more than 20 percentage points above comparable attainment rates in the United States. Korea also has a top-quality school system when measured by student performance in standardized tests: The country consistently ranks among the best-performing countries in the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA).

At the tertiary level, Korea’s universities have less of a resounding global reputation; nevertheless the country was ranked 22nd among 50 countries in the 2018 Ranking of National Higher Education Systems by the Universitas 21 network of research universities. The Economist Intelligence Unit, meanwhile, recently ranked Korea 12th out of 35 countries in its “Worldwide Educating for the Future Index,” tied with the United States.

Korea’s high educational attainment levels are but one sign of the country’s singular transformation and meteoric economic rise over the past 70 years. Along with the other Asian “tiger economies” of Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, Korea represents one of the most remarkable economic success stories of the 20th century, envied by many developing countries up to today.

In the 1950s, after the devastating Korean War, Korea was still an impoverished agricultural society and one of the poorest countries in the world. Today, it is the world’s 12th largest economy and the fourth largest in Asia. Seoul—Korea’s capital and main metropolis with nearly 10 million inhabitants—is said to have the highest gross domestic product (GDP) per capita after Tokyo, New York, and Los Angeles. Contemporary Korea is an advanced high-tech nation with one of the highest Internet penetration rates on the globe.

A laser focus on education was an important pillar of this extraordinary economic rise. In the 1980s, Korea’s government began to strategically invest in human capital development, research, and technological innovation. Korean households simultaneously devoted much of their resources to education, thereby fueling a drastic expansion in education participation. Between the early 1980s and the mid-2000s, the country’s tertiary gross enrollment ratio increased fivefold, while the number of students in higher education jumped from 539,000 in 1980 to 3.3 million in 2015, per UNESCO data.

In fact, it’s hard to find another country in the world that places greater emphasis on education than South Korea. Educational attainment in contemporary Korea is of paramount social importance and strongly correlated with social mobility, income levels, and positions of power. Graduates of Korea’s top three universities dominate the country and occupy the majority of high-ranking government posts and management positions in Korea’s powerful business conglomerates (chaebols).

Competition over admission into top universities is consequently extremely fierce, underscoring Korea’s reputation for having one of the most merciless education systems in the world—usually described as “stressful, authoritarian, brutally competitive, and meritocratic.” Consider that the country’s students devote more time to studying than children in any other OECD country, while parents spend large parts of their income on private tutoring in what has been dubbed an “educational arms race.” The country is said to have the largest private tutoring industry in the world.

By some accounts, many Korean children spend 16 hours or more a day at school and in after-class prep schools, called hagwons. A 2014 survey by Korea’s National Youth Policy Institute found that nearly 53 percent of high school students didn’t get enough sleep because they studied at night; 90 percent of respondents said that they had less than two hours of spare time on weekdays.

Observers, thus, have described Korean society as having an “almost cult-like devotion to learning,” with students being “test-aholics” steered by “tutor-aholic” parents. Studying long hours at hagwons has become so ubiquitous and excessive that Korean authorities in the 2000’s deemed it necessary to impose curfews, usually at 10 p.m., and patrol prep schools in areas like Seoul’s Gangnam district, where many of these schools are concentrated—only to drive nighttime cram classes underground behind closed doors.

This extreme competitiveness has created a number of social problems: Suicide, for instance, is the leading cause of death among teens in Korea, which has the highest suicide rate overall in the entire OECD. Student surveys have shown that poor grades and fears of failure are major reasons for suicidal thoughts, while Korea simultaneously has a growing teenage drinking problem.

Social pressures to succeed in the labor market, meanwhile, have given rise to a phenomenon called “employment cosmetics”—one of the driving factors behind Korea’s boom in cosmetic surgery, since job applicants are commonly required to submit an ID photo, and many employers factor physical attractiveness into their hiring decisions. In another sign of competition at any cost, private household debt in Korea is soaring, driven in part by surging expenditures on education and private tutoring.

Social pressures are further amplified by Korea’s relatively high youth unemployment rate, which stood at 11.2 percent in 2016—a record number not seen since the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s. Despite all the time, finances, and emotional resources invested in their education, Korean youth find it increasingly difficult to secure desired quality, socially prestigious jobs. The country’s obsession with higher education continues to sustain a “college education inflation,” flooding the Korean labor market with a supply of university graduates that hold degrees of deflated value whose earnings prospects are decreasing.

While a university degree used to be a solid foundation for social success in Korea, observers have noted that many current graduates lack the skills needed for employability in a modern information society, and that the education system is too narrowly focused on university education, while underemphasizing vocational training. Korea’s Confucian-influenced system has also been criticized for relying too much on rote memorization and university entrance prep at the expense of creativity and independent thought.

Notably, and perhaps counterintuitively, the growing unemployment rates among recent university graduates and the increasingly ferocious competition in Korea’s education system exist despite Korea being one of the fastest-aging societies in the world. The country’s fertility rates are in rapid decline, and its college-age population is shrinking.

By 2060, more than 40 percent of the Korean population is expected to be over 65, and the country’s population is projected to shrink by 13 percent to 42.3 million in 2050. This cataclysmic demographic shift is already causing the closure of schools and universities, as well as reductions in university admissions quotas. If this aging trend can’t be reversed, it could lead to severe labor shortages and jeopardize Korea’s prosperity, if not ruin the country. Korean youths will likely find it much easier to find employment, but they will shoulder the heavy burden of supporting the country’s rapidly growing elderly population.

Education Reforms Under Korea’s New Government: Creating a Less Competitive System

At present, there is already adamant political pushback in Korea against the current state of affairs, notably the rampant favoritism and nepotism in the hiring practices of Korea’s all-powerful chaebols and corruption in the Korean government, laid bare in the criminal embezzlement scandal that led to the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye. Following the scandal, leftist President Moon Jae-in won a landslide election victory in May 2017 running on an anti-corruption platform that included promises to reform the education system and reduce youth unemployment.

Moon’s bold education reform proposals seek to eventually integrate all state universities into one large university system. The goal is to reduce competition between institutions and equalize the chances of graduates in Korea’s cutthroat labor market, which is heavily skewed toward graduates of Seoul’s top universities.

The government also plans to reduce university admissions fees, and decongest school curricula and make them more flexible by introducing more elective subjects. Elite private high schools (autonomous schools) and international schools that teach foreign curricula are slated to be turned into tuition-free schools that teach standard national curricula in order to rein in elite schools.

To ensure the longevity of the reforms irrespective of changes in government, they are intended to be implemented by a new independent state education committee, rather than the politically controlled Ministry of Education (MOE). That said, as of this writing no concrete steps have yet been taken to form this new committee.

But the Moon administration is certainly pushing ahead with reforms. Current policy initiatives focus on decreasing competition in university admissions, thereby making access to education and employment more socially equitable, and reducing the influence of prestigious universities, notably the country’s top three institutions: Seoul National University, Korea University, and Yonsei University, collectively referred to as “SKY universities.” Since admissions tests at top universities are so demanding that they can only be passed with the help of extensive private tutoring, the government in 2017 ordered several universities to ease their admission tests—a move intended to curb private tutoring and improve the chances of students from low-income households, who are unable to afford expensive prep schools.

Other recent reforms include the adoption of “blind hiring” procedures in the public sector—a practice the government wants to extend to the private sector as well. Under the new guidelines, applicants no longer have to reveal the name of their university or GPAs on their application, nor provide personal information about age, weight, or family background, or submit a head shot.

The goal of the reforms is to make hiring decisions based mostly on specific job-related skills. Some private employers have started to hire candidates based on audition-type presentations or skills examinations, rather than academic and personal background, but there is nevertheless strong resistance to blind hiring from companies and privileged graduates of top universities. President Moon’s education reform agenda is no doubt ambitious and groundbreaking, but it remains to be seen if the government can prevail in realizing all its objectives, given the vested interests of elitist “old-boy networks” in chaebols and top universities.

Outbound Student Mobility

Despite a recent slump in overseas enrollments by Korean students, Korea is one of the top sending countries of international students worldwide after China, India and Germany. The number of Koreans enrolled in degree programs abroad peaked at 128,994 in 2011, after doubling from 64,943 in 1997, according to data provided by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS). Since then, the number of degree-seeking Korean international students has decreased by 15.8 percent to an estimated 108,608 students in 2017.

Trends in Korean outbound mobility are driven by a number of influences, including economic factors, increased participation rates and demand-supply gaps in higher education, demographic trends, and the rising demand for English language education.

In the decades leading up to the 2011 peak, the number of Korean youths completing upper-secondary school surged, drastically increasing the pool of potential international students, while simultaneously exacerbating supply shortages that made access to quality university education increasingly difficult and competitive. Robust economic growth and rising prosperity simultaneously allowed more people to afford an overseas education.

The rapid expansion of the higher education system also led to the creation of growing numbers of private institutions of lesser quality with only a minority of the very best students admitted to the top institutions. This trend incentivized greater numbers of students to pursue education abroad, especially since Korean society came to value English-language education. These developments created a fertile environment for Korean outbound student mobility.

Korea’s demographic decline has since shrunk the college-age population and reduced the number of Korean students, affecting not only domestic enrollments, but also the total number of students heading overseas: The country’s outbound student mobility ratio1 has dropped from 3.8 percent in 2011 to 3.3 percent in 2016. That said, the current downturn is not only due to demographic change.

Reasons for the Slowdown in Outbound Student Flows

One of the reasons for this contraction is that it has become increasingly difficult for Koreans to afford an expensive overseas education. Korea’s economic expansion has lost steam in recent years, making double-digit growth rates a thing of the past—GDP growth dropped from 6.5 percent in 2010 to 3 percent in 2017 (World Bank).

Korea’s economic slowdown has been accompanied by rising household debt, which hit a record high in 2017, fueled by soaring housing costs, high interest rates, and growing expenditures on education, including private tutoring. The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) noted in a 2013 study that more than 50 percent of middle class households were “cashflow-constrained” and that Korea now has the lowest private savings rate in the OECD.

In addition, unemployment among university graduates is not only high, it exceeds unemployment rates among graduates of vocational high schools, leaving many families doubting if an expensive university degree is still worth it, according to MGI.

With respect to overseas education, such considerations are likely influenced by the fact that some Korean employers are reluctant to hire graduates of foreign schools. In fact, a foreign degree can be a liability in Korea’s hierarchical work environment. Graduates of overseas schools lack the social connections domestic students are able to develop—which are so critical to finding employment in Korea. As the New York Times put it, the “edge that a foreign degree gives a South Korean graduate” has worn off in the wake of ever-increasing numbers of Koreans earning foreign degrees. Many Korean families now worry “that overseas study is no longer the guarantee of economic security that it once was.”

Moreover, since Korean universities increasingly offer English-taught programs, there is less incentive to study abroad to improve English skills. Dwindling student numbers, meanwhile, have narrowed the demand and supply gap in higher education to the extent that the Korean government is now forced to close down growing numbers of universities. This is bound to affect cost-benefit calculations, especially since the Korean government is simultaneously undertaking heightened efforts to improve the quality of its higher education institutions (HEIs), while ramping up scholarship funding.

The Korean government recently also subsidized the establishment of foreign branch campuses on a newly created “global university campus” in the Incheon Free Economic Zone close to Seoul. Having foreign branch campuses in Korea means that Koreans can now earn a foreign degree without leaving the country. The State University of New York at Stony Brook, George Mason University, the University of Utah, and Belgium’s Ghent University now operate branch campuses in Incheon. In addition, Germany’s University of Nürnberg is running a branch campus in Busan, while the STC-Netherlands Maritime University operates a campus in Gwangyang City, and the Scottish University of Aberdeen is expected to soon open a campus at Hadong.

Korean Students in the U.S.

The U.S. is by far the most popular study destination among Korean students. Fully 57 percent of Koreans enrolled in degree programs abroad studied in the U.S. in 2017, followed by Japan (12 percent), Australia (6 percent), the United Kingdom (5 percent), and Canada (4.5 percent), as per UIS data. France, Malaysia, New Zealand, China, and Italy are other top destination countries for Koreans.

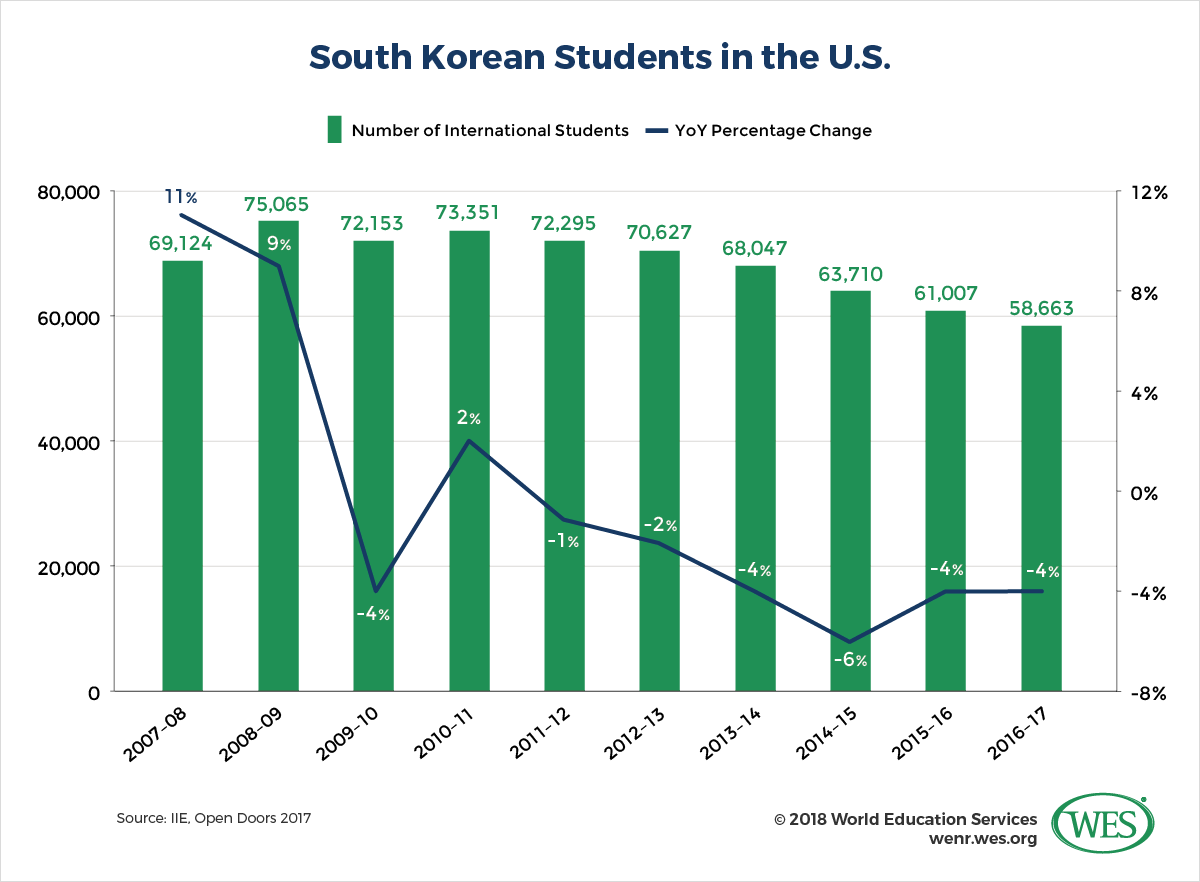

In the U.S., Korea remains the third-largest sending country of international students after China and India, despite a significant drop in enrollments in recent years. According to the Open Doors data of the Institute of International Education (IIE), Korean enrollments declined by almost 22 percent since the 2008/09 academic year and stood at 58,663 in 2016/17. Year-over-year enrollment growth from Korea has persistently declined since 2011/12, whereas year-over-year growth for China and India increased by approximately 12 percent and 7 percent, respectively.

Further declines are likely. According to SEVIS student visa data provided by the Department of Homeland Security, the number of Koreans holding active F and M student visas decreased from 71,206 to 67,326 between March 2017 and March 2018.

The most popular fields of study of Korean students in the U.S. are business and management, engineering, social sciences, and fine and applied arts, according to Open Doors. Most Korean students study at the undergraduate level. Between 2015/16 and 2016/17, undergraduate enrollments declined by 8 percent while graduate enrollments only dropped by about 1 percent. However, 51 percent of students were still enrolled at the undergraduate level, compared with 28 percent at the graduate level and 21 percent in Optional Practical Training and non-degree programs.

By most accounts, Korean students are interested in studying in the U.S. because of the standing and reputation of U.S. institutions in world university rankings. They also want to learn English, acquire experience abroad, and improve their employment prospects in Korea. However, as mentioned before, the return on investment in a foreign degree has diminished, and Korean students are increasingly strapped for funds. Rising tuition costs in the U.S. therefore don’t work in favor of increased student inflows from Korea.

Other Destination Countries

The picture in other destination countries is mixed. Per UIS, the number of Korean students enrolled in degree programs in Japan has plunged by more than 50 percent since 2011 and decreased from 25,961 students to only 12,951 students in 2016, although Korea is still the fourth-largest sending country in Japan overall. Australia, likewise, saw Korean enrollments in degree programs drop by 23 percent between 2011 and 2016 despite a record-breaking surge in international enrollments in general. According to the latest Australian government data, this downward trend is currently continuing.

China, on the other hand, is quickly becoming a popular destination. According to IIE’s Project Atlas, the number of Korean students in China increased by more than 11 percent since 2013 and currently stands at 70,540. Since China is Korea’s most important trading partner, fluency in Mandarin is a considerable asset in Korea’s job market. As NAFSA’s International Educator notes, geographic proximity, cultural similarities, and lower tuition costs than in Western countries are other draws for Korean students. Korea is currently the largest sending country of international students to China, as per Project Atlas. (Note that Project Atlas data, like other data cited below, are not directly comparable to UIS data, since they are based a different method for counting international students).2

Despite the growing attractiveness of China, English remains the most coveted foreign language for Koreans, and Korea is one of the largest markets for English language training (ELT) worldwide. Instead of enrolling in academic degree programs in countries like the U.S., growing numbers of Koreans now seek to improve their English skills in more affordable ELT schools in places like Malta or the Philippines.

As we noted in another article, the Philippines in particular has become a popular “budget ELT destination” for Koreans “that is easily reachable via short direct flights and affords students the opportunity to combine ELT with beachside vacations.” The Philippines’ ambassador to the U.S. stated in 2015 that “there are more and more Koreans … studying English in the Philippines…. In 2004, there were about 5,700…. The following year, it tripled to about 17,000, in 2012 it was about 24,000.” Meanwhile, in the U.S., Korean ELT enrollments have dropped by 17 percent since 2015.

Korean Students in Canada

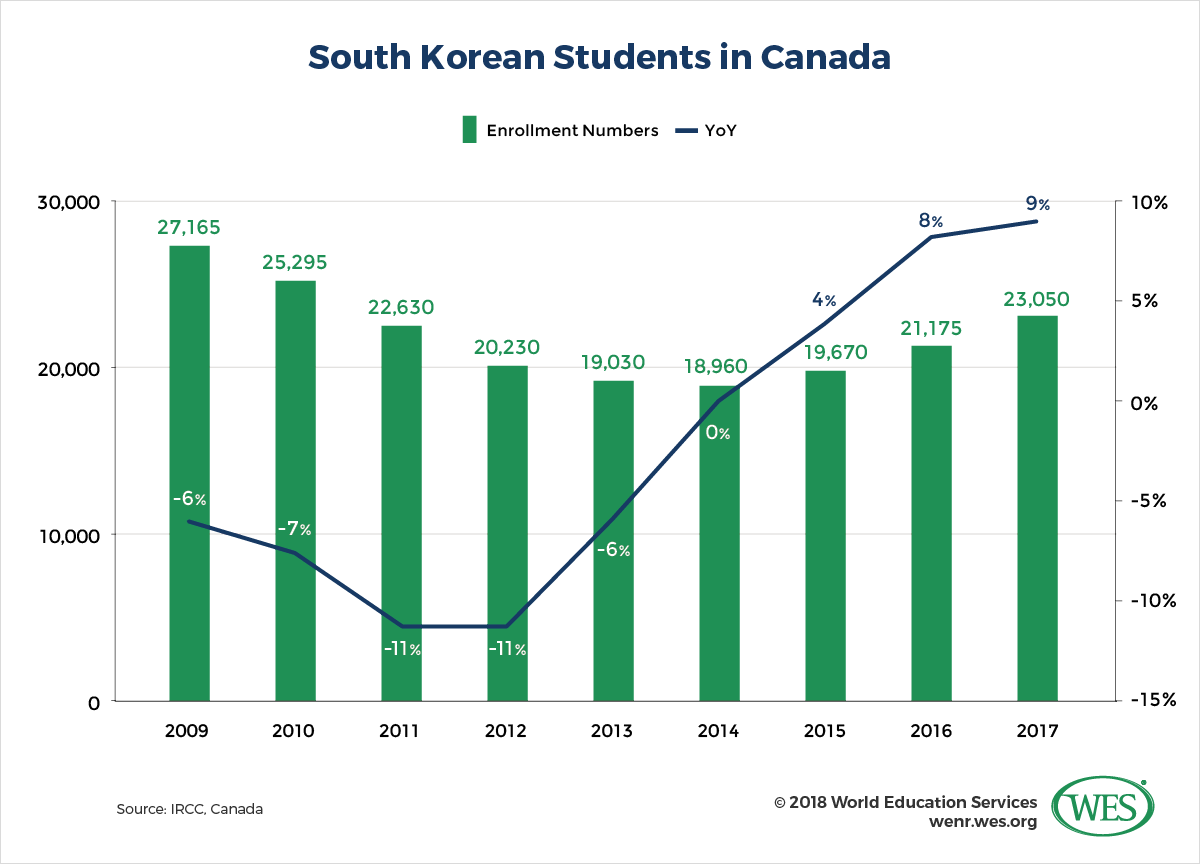

The number of Korean students in Canada has declined significantly over the past decade. In 2000, Korea used to be the largest sending country of international students, but it has since been taken over by China and was in 2010 pushed to third place amid surging enrollments from India. According to statistics from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), there were 23,050 Korean students in Canada in 2017—25 percent less than in 2007 when enrollments peaked at 36,800. However, since 2015 Korean enrollments are back on a growth trajectory and have most recently increased by 9 percent between 2016 and 2017.

The reasons for this reversal are unclear, but the shift in trends coincided with Canada expanding its admission quotas for skilled immigrants—a factor that may have played at least some role in attracting more Koreans to the country. Korea is the 10th largest country of origin of recent immigrants in Canada; 6.5 percent of Korean international students in Canada transitioned to permanent residency in 2015 (the fourth largest group after Chinese, Filipinos, and Indians). The growing unpopularity of the U.S. in the Trump era, and opportunities to participate in research collaborations and scholarship programs, may also have played a role. ELT, on the other hand, doesn’t appear to be a factor—Korean ELT enrollments have remained flat between 2014 and 2017, despite increased recruitment efforts by Canadian ELT providers.

Inbound Student Mobility

Korea currently pursues an internationalization strategy that seeks to increase the number of international students in the country to 200,000 by 2023. Attracting more international students is considered necessary to compensate for declines in domestic enrollments and to strengthen the international competitiveness of Korea’s education system. Various measures have been adopted to achieve these objectives. They range from scholarship programs and marketing campaigns, to the easing of student visa requirements and restrictions on post-study work, as well as allowing Korean universities to set up departments and programs specifically for international students.

These efforts are bearing fruit. Korea today has four times as many international students than in 2006, and it is becoming an increasingly important international education hub in Asia. Korea’s ambitions were set back when the number of international students declined between 2012 and 2014, but inbound mobility has since increased strongly. In 2018, the number of international students enrolled in degree and non-degree programs reached a record high of 142,205, after growing by 70 percent over 2014. According to the latest available government statistics, 37 percent of international students were enrolled in undergraduate programs in 2016, compared with 23 percent in graduate programs and 39.5 percent in non-degree programs.

The overwhelming majority of international students in Korea come from other Asian countries—in 2018, 48 percent of students came from China, followed by Vietnam (19 percent), Mongolia (5 percent), and Japan (3 percent). Other sending countries include the U.S., Uzbekistan, Taiwan, France, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Between 2016 and 2017, the number of Chinese students spiked by more than 13 percent, while enrollments from Vietnam skyrocketed by 96 percent. More than 57 percent of international students study in the Seoul metropolitan area.

Despite these increases in international student inflows, Korea still struggles to fully open up to the outside world and internationalize its education system. Surveys have shown that students from China and other Asian countries often feel discriminated against and face high hurdles when seeking employment after graduation. Foreign Western faculty, meanwhile, reportedly feel unintegrated; many of them leave after short tenures. As Korean researchers have noted, there is not enough intercultural exchange between domestic and international students in Korea’s sometimes exclusivist culture. They criticize that the growing diversity on Korean campuses is “just for show … that Korean universities primarily attract foreign students as a means to clear ends. The universities want them to come to enhance university prestige or create ‘education hubs’ and [improve] international higher education rankings.”

In Brief: The Education System of South Korea

Korea’s education system underwent a tremendous expansion since the end of the Korean War. In 1945, Korea had an estimated adult literacy rate of only 22 percent. Less than 2 percent of the population was enrolled in higher education. Today, the country has achieved universal adult literacy, estimated to range between 98 and 100 percent, and the tertiary gross enrollment ratio stands at a lofty 93 percent (2015).

Influenced by the U.S. occupation of South Korea, the country adopted a school system patterned after the U.S. system: It comprises six years of elementary education and six years of secondary education, divided into three years of middle school and three years of high school.

In the 1950s, elementary education was made compulsory for all children, which led to the universalization of elementary education by the 1960s. Beginning in 1985, the length of compulsory education was then extended by another three years, and all children in Korea are now mandated to stay in school until the end of grade nine (age 15). In reality, however, this minimum requirement is of little practical relevance in present-day Korea. As of 2014, 98 percent of Koreans went on to upper-secondary and completed high school at minimum. The advancement rate from lower-secondary middle school to upper-secondary high school stood at 99 percent as early as 1996.

Since the 1960s, enrollment rates in the school system spiked drastically in tandem with rapid industrialization and the achievement of universal elementary education. According to data provided by the Korean MOE, the number of high schools in Korea alone increased from 640 in 1960 to 2,218 in 2007, while the number of students enrolled in these schools jumped from 273,434 in 1960 to 2.3 million in 1990. This sudden expansion overburdened the system and resulted in overcrowded classrooms and teacher shortages—problems that caused the Korean government to begin levying a dedicated education tax in 1982 in order to generate revenues for accommodating growing demand.

The aging of the population has since eased pressures somewhat and led to significantly lower numbers of children enrolling in the school system—leading to other problems, discussed below. According to UNESCO data, the number of elementary students dropped from 4 million in 2005 to 2.7 million in 2015, while the number of upper-secondary students recently decreased from close to 2 million in 2009 to 1.8 million in 2015.

This demographic shift has caused the closure of thousands of schools throughout Korea, almost 90 percent of them located in rural regions, which are increasingly being bled out by a rapid out-migration to the cities. As the New York Times noted in 2015, since 1982 “… nearly 3,600 schools have closed across South Korea, most of them in rural towns, for lack of children. Today, many villages look like ghost towns, with … once-bustling schools standing in weedy ruins ….” However, despite this demographic shift, Korea in 2015 still had some of the largest lower-secondary class sizes in the OECD, as well as an above-average teacher-to-student ratio in upper-secondary education—circumstances that are likely due to rapidly growing enrollments in urban areas.

Traditionally, Korean schools have been segregated by sex—coeducational schools did not begin to emerge until the 1980s. Only 5 percent of Korea’s schools were coeducational as of 1996. The number of coeducational schools has since increased significantly, but the majority of Korea’s schools are still single-sex. Even at coeducational schools, individual classes may still be taught separately for girls and boys. In Seoul, about one-third of high schools are coeducational with pupils in the city being randomly assigned to single-sex and coeducational schools.

Administration of the Education System

Korea has 17 administrative divisions: nine provinces, six metropolitan cities—which have equal status to the provinces—and Seoul, which is designated as a special city. In addition there is the special autonomous city of Sejong, which was recently created to become Korea’s new administrative capital in an attempt to reduce the influence of Seoul, Korea’s towering economic and administrative center. Another goal is to stimulate economic development in other parts of the country. Sejong City now houses the majority of government ministries and agencies, including the administrative headquarters of the MOE, which controls most aspects of education.

According to the MOE’s website, it “plans and coordinates educational policies, formulates policies that govern the primary, secondary, and higher educational institutes, publishes and approves textbooks, provides administrative and financial support for all levels of the school system, supports local education offices and national universities, operates the teacher training system and is responsible for overseeing lifelong education and developing human resource policies.”

Korea has historically had a centralized system of government. However, Korea’s administrative divisions and municipal governments have over the decades been given much greater autonomy in terms of budgeting and administration of the school system in order to better accommodate local needs. There were 17 provincial and metropolitan offices and 176 district offices administering education at the local level in 2016. That said, local autonomy is limited and overall education policies are set at the national level, while higher education remains under the auspices of the national MOE.

In devising policies, the MOE relies on advice from the Educational Policy Advisory Council, a body consisting of rotating experts from various fields in education. The quality assurance and accreditation of universities falls under the purview of the Korean Council for University Education (KCUE), an independent, non-governmental university association.

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

The academic year in Korea runs from March to February, divided by a summer break in July/August and a winter break in December/January. Korean children attend classes 5.5 days a week and spend about 220 days a year in school versus 175 to 180 days in the United States. The academic calendar at universities is typically divided into two four-month semesters with a two-month break between each semester.

Korean is the language of instruction in schools, even though private international schools and certain specialized high schools offer English-medium instruction (EMI). In higher education, Korean is still predominant, but EMI has spread rapidly since the 1990s, when the Korean government started to encourage universities to offer English-taught classes. Some universities, like the Pohang University of Science and Technology, now teach more than 90 percent of their courses in English. About 30 percent of lectures at Korea’s top 10 universities were taught in English as of 2013—a sign that EMI is being pursued vigorously by Korean universities, partially because it affects international university rankings and makes Korean institutions more attractive to international students.

English language teaching is generally highly prioritized in Korea, since it’s the language of international business and science, and English competency is highly important for employment prospects, university admissions, and social status. The government systematically promotes high-quality English language teaching, and there have been suggestions by previous governments to make English the main language of instruction in schools. Private households, meanwhile, spend large sums of money on private English tutoring. Many Korean children now start learning English in kindergarten before entering elementary education. This craze for learning English has become so excessive, that the Korean government in 2018 banned the teaching of English prior to third grade, since it appeared to slow pupils’ proficiency in Korean. Officially, English is introduced as a subject in third grade at all Korean schools.

Elementary Education

Elementary education is provided free of charge at public schools and is six years in duration. It starts at the age of six, even though gifted students may sometimes be allowed to enter at age five. Although preschool is not compulsory, about 90 percent of children age three to five attend it.

Many pupils attend private kindergartens, often for the entire day, but the government has over the past decades expanded public options, and since 2012/13 provided universal, free, half-day preschool programs, so as not to disadvantage children from lower-income households. Free public full-day programs are currently being planned as well.

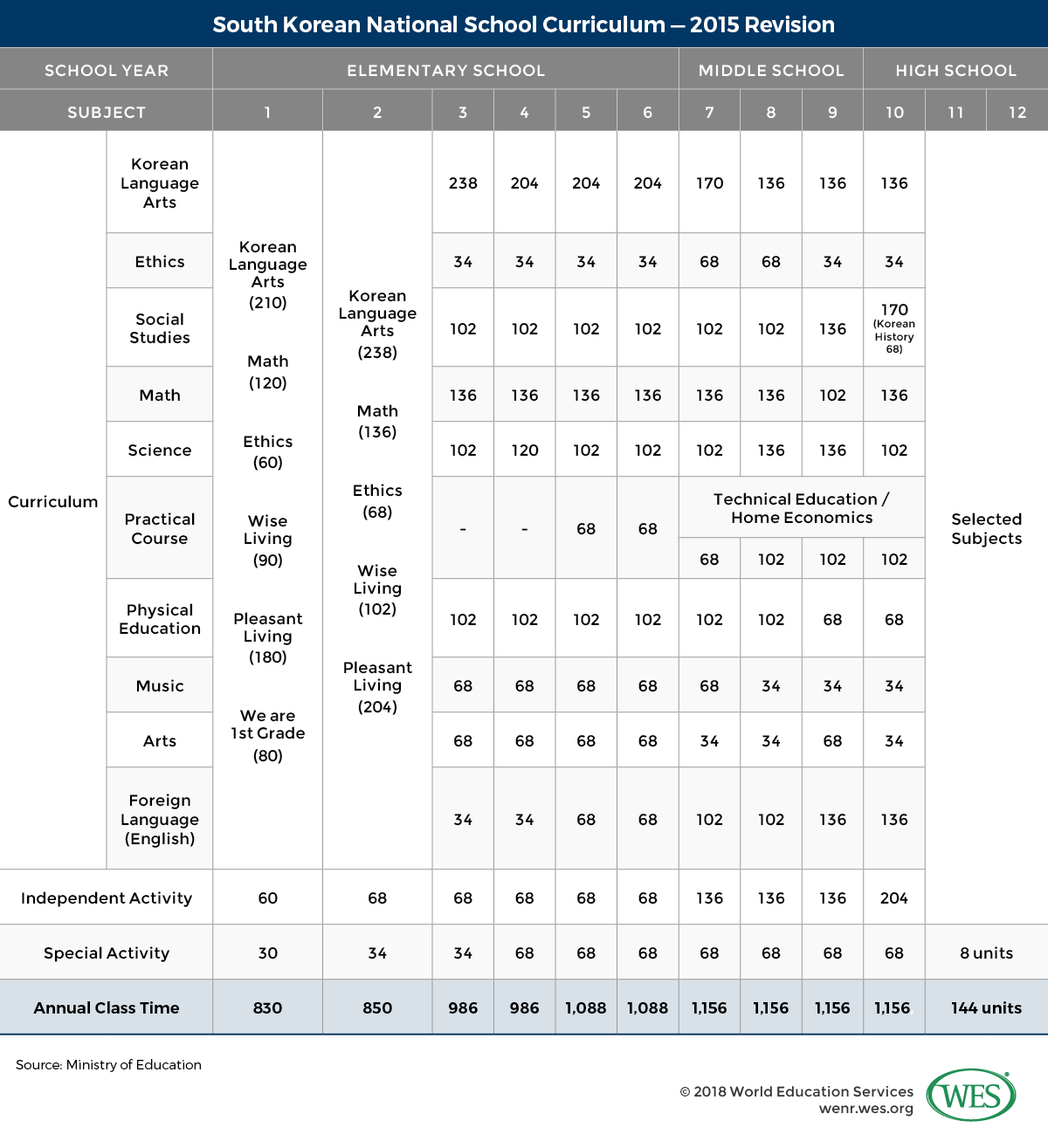

Pupils study a set national curriculum that is updated every 10 years; the latest revision was adopted in 2015. During the first two years, pupils study Korean, mathematics, ethics, and general social formation subjects called “wise living,” “pleasant living,” and “we are first graders.” English, social studies, science, arts, music, and physical education are added in the third grade, at which point the social formation subjects are no longer offered. Promotion and graduation are based on internal school-based tests and assessments at all stages of the Korean school system. In an attempt to move away from an overly test-driven system, the current curriculum emphasizes the fostering of creative thinking and prioritizes essays over multiple-choice tests.

Lower-Secondary Education (Middle School)

Lower-secondary education lasts three years (grades seven to nine) and concludes with the award of a certificate of graduation from middle school. The subjects taught are the same as in elementary education, except for the addition of either technical education or home science. Notably, pupils now enjoy a “free semester” in which they don’t have to take written examinations or pass other school assessments—a change that was introduced to promote “happy education for all children.”

Lower-secondary education is provided free of charge at both public and private schools and is open to all pupils who have completed elementary education—there are no entrance examinations. To avoid competition over admission into desired schools, the Korean government since the 1970s implemented a so-called school “equalization policy” that took admissions decisions away from schools and placed them under government control. Today, this policy covers all middle schools, which means that all elementary school graduates are being assigned to schools within their districts via a computerized lottery system. Private schools are mandated to teach the national curriculum and offer tuition-free education in return for receiving subsidies from the government. According to UNESCO, 18 percent of lower-secondary students and 43 percent of upper-secondary students were enrolled in private schools in 2015.

Upper-Secondary Education (High School)

Upper-secondary education in Korea is neither compulsory nor free. It is much more diversified than lower-secondary education. While all high school programs last for three years (grades 10 to 12), they are taught by a variety of different schools, such as general academic high schools and special-purpose high schools, that offer specialized education in areas like foreign languages, arts, sports, or science.

In addition, there are specialized vocational high schools that offer employment-geared education, as well as designated autonomous high schools, which are mostly privately run elite institutions that have greater autonomy over their curricula, and which were originally created to diversify school options in Korea.

However, the future of these autonomous institutions is currently uncertain. The Moon administration has criticized autonomous schools for being little more than exclusivist prep schools for admission into top universities, and seeks to convert them into regular schools. Autonomous schools are very expensive and elitist, admitting only the highest scoring students, and therefore seen as exacerbating social inequalities.

In 2016, 71.7 percent of upper-secondary students were enrolled in general academic schools, compared with 16.6 percent in specialized vocational schools and around 11.5 percent in autonomous schools and special-purpose schools, although these percentages fluctuate from year to year. Enrollments in vocational schools, for instance, have dropped drastically since the 1990s, presumably because of growing social preferences for university education and Korea’s shift from an industrial to a service-based economy.

Admission requirements at Korean high schools vary and depend on the type and location of the school. Korean authorities have been less forceful in implementing school equalization for high schools than for middle schools—only about 60 percent of upper-secondary schools are currently located within so-called “equalization zones.” In these districts, admission is based on a lottery system, provided that students pass a general competency examination. Outside of equalization zones, however, admission is highly competitive and driven by free market mechanisms, which means that eligibility is usually determined by GPAs and entrance examinations, as well as interviews or teacher recommendations.

General Academic High School

All students in general academic high schools study a common core curriculum in grade 10, which features largely the same subjects as the middle school curriculum. In grades 11 and 12, students then choose elective subjects in addition to common subjects like Korean, mathematics, English, and a second foreign language.

Until recently, students had to choose between a natural science-oriented stream and a liberal arts-focused stream, but these streams have been abolished under the current curriculum. In an attempt to make education more holistic and to foster creative thinking, students can now freely choose subjects from both streams. Available subjects include physics, chemistry, biology, earth science, history, geography, economics, or politics. Most students choose their electives based on their intended field of study in university.

Promotion to the next grade is based on educational assessment and evaluation, with midterm and final exams at the end of each semester. Academic transcripts usually provide detailed information about academic performance, class ranking, and attendance. Students who complete all required 204 credit units are awarded a certificate of graduation from high school.

Specialized (Vocational) High Schools

The name of vocationally oriented high schools has changed over the years—they used to be called vocational high schools, then technical high schools, but are currently referred to as “specialized schools.” Vocational upper-secondary education prepares students for entry into the labor force as skilled workers, as well as for further education. The curriculum is divided into a general education component of about 32 percent. About 42 percent is vocational study, with the remainder devoted to other learning activities, which may include industrial internships.

Students study the standard academic core curriculum in grade 10 before specializing in a vocational field, such as business, agriculture, engineering, technology, fishery, or marine transportation in grades 11 and 12. The majority of vocational high schools currently use learning modules developed by the MOE and the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training on the basis of Korea’s National Competency Standards framework.

Graduates are awarded certificates of graduation that are formally equivalent to high school diplomas from other types of schools and that provide access to tertiary education. However, far fewer (and decreasing) graduates in the vocational track pursue higher education. Many continue their studies at junior colleges rather than at four-year universities.

The Korean government seeks to promote labor market entry directly after high school and strengthen vocational skills training with an “employment first, advancement to university later” approach. To this end, Korea in 2008 established a new type of vocational school, the so-called Meister schools, which teach curricula tailored to industry needs in fields like banking, social services, dental hygiene, maritime industries, or semiconductor development. These curricula are developed in coordination with local companies and incorporate industrial internships; teaching faculty may include industry experts.

Even though only 4 percent of high school students were enrolled in Meister schools as of 2013, these well-funded schools have raised the public’s awareness of vocational high schools in Korea and made them more attractive, especially since the partnering government agencies and companies—which include chaebols like LG Electronics—typically guarantee employment for graduates.

Meister school graduates are not allowed to enroll in universities until they work full time for three consecutive years. However, entry into tertiary education has been eased by growing numbers of HEIs adopting special admissions policies that allow Meister school graduates to enroll without sitting for the national college examinations, after completing their three years of full-time employment.

University Admissions

All Korean high school students who intend to apply to university must pass the national University College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT), commonly called Suneung in Korean, administered by the Korea Institute of Curriculum and Evaluation (KICE). Held in November each year, this high-stakes examination is a major event during which businesses and the stock market open late to prevent traffic jams, while bus and subway services are increased to ensure that students arrive on time. In 2017, about 593,000 high school students registered for the Suneung. Underscoring the importance of the exams, air traffic in Korea is suspended during the listening section of the eight-hour test.

Depending on their desired academic majors, students choose nine examination subjects from the fields of Korean language, mathematics, English, “investigation” (that is, social studies, science, or vocational education), and a second foreign language or Chinese characters (Hanja) and literary classics. Korean history is a mandatory subject for all candidates. Some subjects can be taken at two different levels of difficulty. Students that take the CSAT can apply to three different universities at a time.

The test is mostly in multiple-choice format; the final CSAT report lists the scores as well as percentile rankings in all subjects except for English and Korean history. While the vast majority of candidates pass the test, students who fail can retake it. Increasing numbers of students also retake the exams to improve their scores or because they wish to switch majors.

The CSAT scores are a key admission criterion at many universities; near-perfect CSAT scores are a baseline admission threshold at top institutions like the SKY universities. Several Korean HEIs admit students based on a combination of high school records and the CSAT.

However, universities are not obligated to use the CSAT results for admissions. In 2018, only 22.7 percent of freshman students were admitted exclusively on the basis of CSAT scores, whereas the majority of students were admitted based on other criteria, such as high school grade averages, university admissions tests, essays and letters of recommendation, practical tests, extracurricular activities, or interviews. Most of these admissions are through “early admissions,” for which candidates apply in September before the annual CSAT exams in November.

Even though the Suneung is considered one of the most challenging university entrance examinations in the world, several Korean universities conduct major-related entrance examinations in addition to CSAT, which tests students’ knowledge of the standard high school curriculum. University admissions in Korea are highly competitive, especially at top institutions like the SKY universities, which admit only the top 2 percent of CSAT scorers.

The current Korean government considers the CSAT the most objective and socially equitable admission criterion; it is seeking to increase use of the test in university admissions. It recently mandated that universities admit at least 30 percent of their students based on the Suneung by 2022. At the same time, the MOE is attempting to make passing the examination easier by replacing percentile rankings with absolute grading in the second foreign language and Chinese characters subject tests within the next four years.

In addition, the government promotes policies similar to affirmative action by requiring mandatory special admissions quotas for students from rural regions. Given the ubiquity of private tutoring, students from rural regions and lower income households tend to score lower in the CSAT and are disadvantaged in university admissions in general compared with students from affluent metropolitan centers like Seoul.

Overall, admissions quotas at Korean universities, which are set by the MOE for both public and private institutions, are currently being reduced drastically because of population aging and the concomitant decline in tertiary enrollments. In August 2018, the Korean government announced that more than 50 HEIs will face cuts of up to 35 percent in their student intake in 2019.

Other institutions are urged to voluntarily decrease their intake, or are being merged, ordered to share professors, or closed down altogether. In 2017, the MOE already shuttered eight “unviable” universities. The Korean Educational Development Institute estimated in 2011 that about 100 universities will have to be closed by 2040. By some accounts, the number of tertiary students in Korea will by then have decreased by more than 50 percent.

Higher Education

Like its school system, Korea’s higher education system is patterned after that of the United States. Its standard structure includes associate degrees awarded by junior colleges, and four-year bachelor’s degrees, master’s degrees, and doctoral degrees awarded by universities.

Between 2011 and 2016, the number of Korean students who entered higher education programs declined by 10 percent. After rapidly increasing by 419 percent between 1980 and 2000, the total number of tertiary enrollments in Korea, likewise, has recently decreased from 3.7 million in 2013 to 3.4 million in 2017, as per the Korean Educational Statistics Service (KESS). About 60 percent of these students are enrolled in undergraduate programs at universities, 30.5 percent at junior colleges and other institutions, and 9.5 percent in graduate programs. According to UNESCO, more than 58 percent of tertiary students in 2016 were men, even though enrollments by women have grown appreciably in recent years—in 2000 women made up only a third of the tertiary student population.

Higher Education Institutions

As of 2016, there were 430 HEIs in Korea compared with only 265 in 1990. Exploding demand for university education over the past decades has been accompanied by a rapidly growing number of private providers springing up to accommodate this demand. More than 80 percent of HEIs are now privately owned—a fact that is mirrored in 80 percent of tertiary students being enrolled in private institutions, per UNESCO.

Private HEIs include top research universities like Korea University, Sungkyunkwan University, and Yonsei University, as well as various for-profit providers of lesser quality. The size, quality, and funding levels of Korea’s HEIs differ greatly, resulting in a stratified university system dominated by prestigious top institutions in Seoul. The largest Korean HEI in terms of enrollments is the Korea National Open University, a public distance education provider with more than 136,000 students headquartered in Seoul.

Korea’s HEIs have historically been tightly regulated by the government, even though restrictions on universities have been eased significantly since the mid-1990s, and the MOE currently seeks to further increase the autonomy of HEIs. Public institutions are directly supervised by the MOE and private HEIs operate under similar rules as public institutions. In other words, they are constrained by a higher degree of regulation than private HEIs in other countries.

Korean HEIs include 138 junior colleges, the vast majority of them private, and 189 universities—a group that comprises national universities and private institutions. Most universities are multi-disciplinary institutions that comprise multiple departments, but there are also mono-specialized universities like the engineering-focused Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. In addition, there are 10 specialized universities of education, two industrial universities, a number of polytechnics, and distance education universities, as well as other providers like “intra-company universities” set up for employees in specific industries. There are 1,153 graduate schools, almost all of which are incorporated into universities, but may also operate as stand-alone institutions. (All numbers are according to 2017 KESS statistics. For a classification of different types of HEIs, see the MOE’s website.)

Beyond merging and closing institutions amid demographic decline, the Korean government currently seeks to strengthen industrial-academic cooperation and restructure several universities into smaller, more specialized, and more research-oriented institutions that have greater autonomy in order to create world-class institutions that concentrate on graduate education. Universities in provincial regions are being supported through the imposition of mandatory employment quotas for local graduates in local industries.3

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

HEIs can only be set up with the approval of the MOE, which has wide-ranging authority over matters like curricula, degree structures, admissions quotas, or the hiring of faculty. In 2010, Korea implemented a mandatory independent accreditation process for universities under the purview of the Korean University Accreditation Institute (KUAI), an organization affiliated with the Korean Council of University Education, a private association of Korea’s universities. In addition to institutional KUAI accreditation, degree programs in professional disciplines are accredited individually by bodies like the Accreditation Board for Engineering Education of Korea, the Korean Institute of Medical Education and Evaluation, or the Korea Architectural Accrediting Board.

Institutional KUAI accreditation is granted for periods of five years, whereas program-based accreditation is typically granted for periods of from four to six years. In the case of shortcomings, institutions and programs are accredited conditionally for two- or three-year periods during which institutions must address inadequacies. Institutions are evaluated via self-assessment, site inspections, and other objective criteria.

Quality criteria stipulated by the KUAI include adequate financial and management structures, teaching staff, facilities, student retention rates, learning outcomes, research output, student satisfaction, and commitment to quality improvement and social contributions to local communities and economic development. As of 2018, 170 universities had obtained accreditation from KUAI.

To promote quality in higher education and establish criteria for the inevitable downsizing and closure of HEIs, the government of former President Park Geun-hye also introduced a new evaluation system for HEIs that ranked universities in five different categories, from excellent to very poor (A to E). HEIs ranked excellent were allowed to voluntarily reduce their student intake, while all others became subject to mandatory capacity cuts, funding cuts, or merger or closure, depending on their ranking. More than 25 universities were classified as poor in 2017 and are in danger of closure in the near future.

In response to sharp criticism of the ranking, the Moon administration has made some changes to the evaluation process, but in 2018 ordered further cuts in university seats, which are slated to be reduced by an additional 120,000 seats by 2023. Ranking is tied to government funding: Top-performing HEIs are designated as “autonomously competent” institutions and rewarded with higher funding levels.4

International University Rankings

Given Korea’s high level of economic development and its strong focus on education, Korean top universities don’t fare as well in international university rankings as Korean policy makers would like them to. Various initiatives, from the “Brain Pool” and “Brain Korea 21” programs of the 1990s to the current Industry-University Cooperation project, have therefore been dedicated to boosting the research output and international competitiveness of Korean universities.

In the late 2000s, Korea allocated approximately USD$600 million to the recruitment of foreign researchers in an initiative called “world class university” program. Such initiatives helped to significantly increase the percentage of foreign faculty at Korean HEIs5 and fueled rapid increases in research output. For instance, Korea is now the world’s leading country in publishing academic research in collaboration with industry partners. However, despite strong advances in modernization and internationalization, the Korean education system is still somewhat insular and its HEIs continue to trail other Asian countries like China, Japan and India in terms of international journal citations and other ranking criteria like employer reputation.

There are two Korean universities ranked among the top 100 in the current 2019 Times Higher Education World University Rankings – the flagship Seoul National University – SNU (ranked at 63rd place) and Sungkyunkwan University, a private institution said to be East Asia’s oldest university, at position 82. This compares to three Chinese, two Japanese and two Singaporean universities among the top 100. Ten Korean universities are included in the current Shanghai (ARWU) Rankings, but none among the top 100. This compares to 51 Chinese universities and 16 Japanese included in the top 500, six of them among the top 100. SNU and Sungkyunkwan University are the highest ranked Korean institutions.

In the QS World University Rankings, Korean universities have advanced noticeably in recent years – there are now five Korean universities featured among the top 100 compared with only three in 2016. Seoul National University ranks 36th worldwide and is the 11th highest ranked institution among Asian universities, followed by the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (rank 40), Pohang University of Science and Technology (83), Korea University (86), and Sungkyunkwan University (100).

Education Spending

Compared to other OECD countries, a high share of education expenditures in Korea is borne by private households making said expenditures a pressing social issue – fully 64 percent of tertiary education spending came from private sources in 2015. The share of private spending in elementary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education is much lower – 14 percent in 2013 – but total private expenditures related to schooling are rising and reached a record high in 2017.

Both public and private HEIs, in particular, are heavily dependent on tuition fees, which average USD$8.500 per annum and range anywhere from USD$1,500 to USD$20,000 per semester, depending on the program and institution. Tuition fee hikes caused growing social resistance and student protests in recent years. In response, the Korean government enacted substantial tuition cuts and expanded scholarship funding. Korean students are also eligible for government loans.

Overall, public spending on education has increased significantly in recent years, causing the share of private expenditures to drop by 24 percent between 2008 and 2013, according to the OECD. Per UNESCO, public education spending as a share of GDP grew from 4.86 percent in 2011 to 5.25 percent in 2015. While that is pretty high for a developed economy, government spending per tertiary student still remains below OECD average. Education spending as a percentage of all government expenditures has fluctuated over the past decade and stood at 18.2 percent in 2017.6 Total government expenditures on education have tripled since 2000 and will be increased by another 10.5 percent to 70.9 trillion won (USD$63.9 billion) in 2019.

Credit System and Higher Education Grading Scales

The credit system and grading scales used by Korean HEIs closely resemble those of the United States. One Korean credit unit usually denotes one contact hour (50 minutes) taken over 15 or 16 weeks, and most courses bear three credit units. Most four-year bachelor’s programs require at least 130 credits for graduation, even though 140-credit programs also exist. Two-year master’s programs usually require at least 24 credits plus a thesis for graduation, but some programs have higher credit requirements.

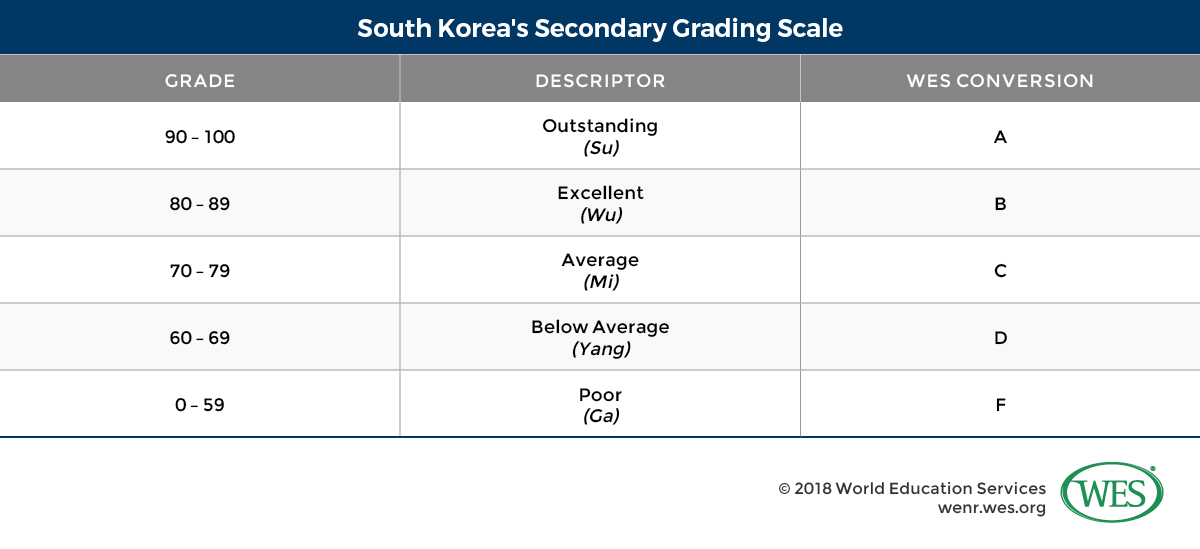

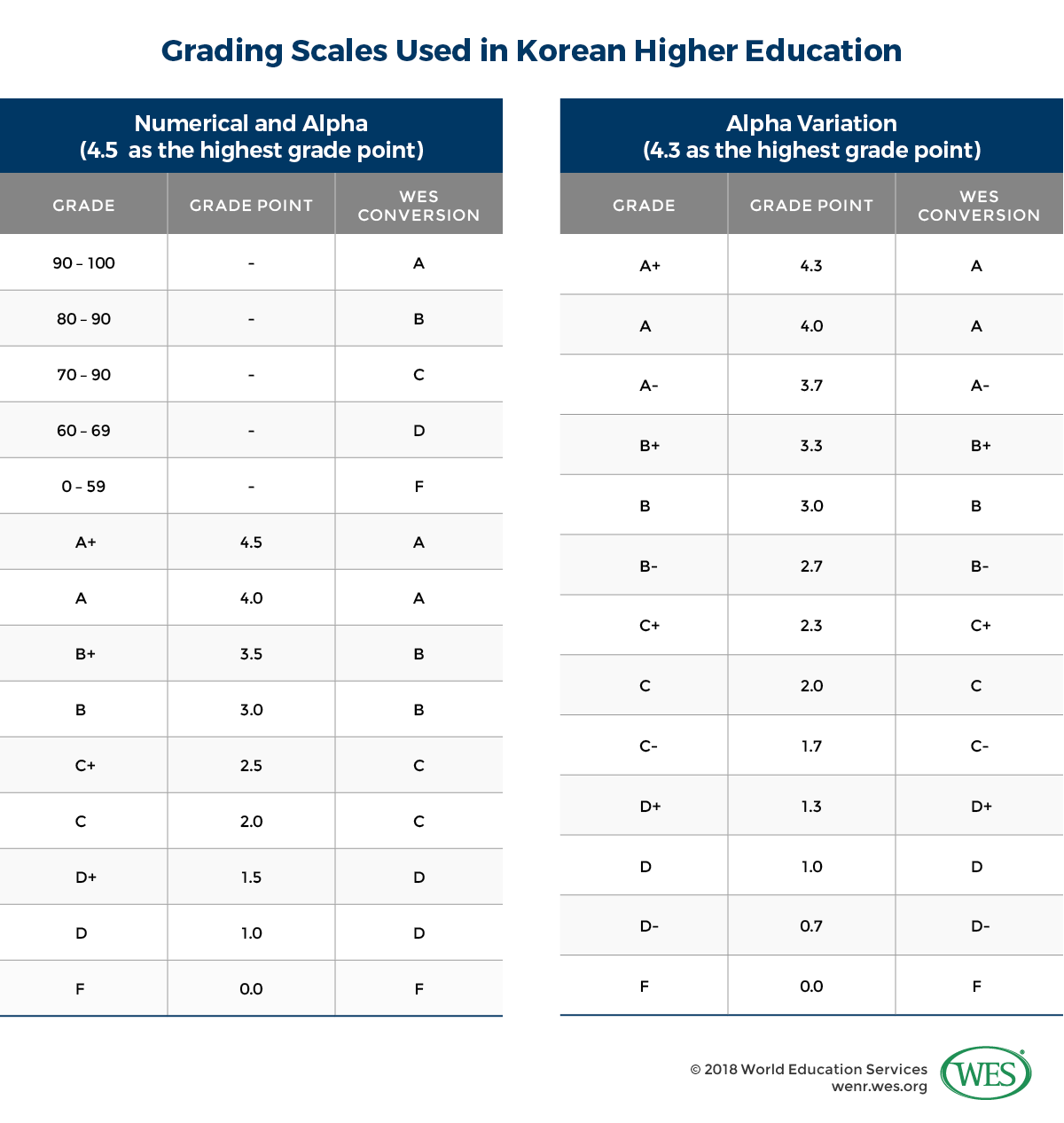

Typical grading scales include 0-100 numerical scales with 60 (D) being the minimum passing grade for individual courses at the undergraduate level. In addition, there are A-F letter grading scales, of which there are two variations with either 4.3 or 4.5 as the highest grade point (see below). Graduation from undergraduate programs usually requires an overall grade point average of at least 70 or C (2.00). At the graduate level, graduation generally requires a minimum final GPA of 3.0 (B or 80). The passing grade for individual courses in graduate programs may be higher than in undergraduate programs (that is, 70 or C). Academic transcripts commonly feature grading scale legends, as well as an explanation of the credit system.

The Higher Education Degree Structure

Associate Degrees (Junmunhaksa)

Korea’s junior colleges, polytechnics, industrial universities, and some other universities offer two- or three-year vocationally oriented post-secondary programs leading to associate degrees in fields like engineering, business administration, health care, fashion design, social work, secretarial studies, or agriculture. Most programs are two years in length (75 to 80 credits), but three-year programs (120 credits or more) also exist in fields like nursing, rehabilitation therapy, early childhood education, interior design, or broadcasting. The final credential may simply be called Associate Degree, or Associate of Science, or Associate of Arts.

Curricula typically include a general education component of about 30 percent in addition to major-specific subjects, with an increasing emphasis on internships. Students are assessed by examinations taken in the middle and at the end of each semester. Junior colleges are focused on training mid-level technicians, but students can also transfer credits to four-year programs (much the same as community college students in the U.S. can) under junior college-university agreements.

Bachelor’s Degree (Haksa)

Bachelor’s degrees are awarded by universities and four-year colleges. Programs in standard academic disciplines are four years in length (at least 130 credits), while bachelor’s programs in professional disciplines like architecture, pharmacy, or medicine take five or six years to complete (see also the section on medical and dental education below). As in the U.S., curricula include core and elective general education subjects, predominantly taken within the first two years, and mandatory and elective subjects in the major. A thesis, project, or comprehensive examination is usually required for graduation, in addition to a cumulative GPA of at least C (2.00). Some programs may be studied in part-time mode. Standard degrees awarded include the Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science, but there is a multitude of credential names, such as the Bachelor of Economics, Bachelor of Information Science, or Bachelor of Statistics, etc.

Students may also earn a degree in self-study mode through Korea’s National Institute for Lifelong Education (NILE). To earn a self-study degree, students must pass a qualifying examination conducted by the government for each year of study. In addition, Korea has a so-called Academic Credit Bank System (ACBS) that allows older adults who have not completed a degree to earn one by combining credit units earned at different institutions. If students complete the required courses set forth in standardized ACBS curricula, the MOE either directly issues an associate or bachelor’s degree to these students, or authorizes HEIs to do so.

Master’s Degree (Suksa)

Master’s degree programs (Suksa) are two years in length and studied in graduate schools, most of which are incorporated into universities. Admission is typically based on the completion of a bachelor’s degree with a GPA of at least 3.0, entrance examinations in the intended field of study and English and, often, selection interviews. Completion of the program requires at least 24 credits of course work, a thesis, and a grade point average of B (3.0) or better. Credential names include the Master of Arts, Master of Science, and numerous other major-specific variations.

Doctoral Degree (Paksa)

The doctoral degree is a terminal research degree awarded by graduate schools. As in the U.S., programs may be structured as integrated programs entered on the basis of a bachelor’s degree with students earning a master’s degree en route, or as stand-alone programs that do not include a master’s degree. In the latter case, programs usually take at least three years to complete, including two years (30 credits) of course work, a passing score on a comprehensive examination, and the defense of a dissertation. Students must also demonstrate proficiency in two foreign languages and maintain a GPA of 3.0 or better. Integrated programs take four years to complete at minimum, including 60 credit units of course work. The most commonly awarded credential is the Doctor of Philosophy, but there are also credentials like the Doctor of Science or applied doctorates like the Doctor of Business Administration.

Medical and Dental Education

Entry-to-practice degrees in medicine and dentistry are either earned upon completion of long single-tier programs of six-years’ duration entered after high school, or four-year graduate-entry programs on top of a bachelor’s degree. In the case of undergraduate programs, the curriculum includes two years of pre-medical science education and four years of medical studies and clinical practice. Graduate-entry programs don’t include the pre-medicine component, but students must pass a medical or dental education eligibility test and are expected to have completed certain prerequisite courses. Most medical schools in Korea offer programs of the undergraduate variety.

Credentials awarded are the Bachelor of Medicine or Doctor of Medicine, and the Bachelor of Dentistry, Doctor of Dental Medicine, or Doctor of Dental Surgery. To become licensed practitioners, graduates need to pass a comprehensive national licensing examination. Certification in medical specialties requires an additional one-year clinical internship and three years of residency training followed by an examination in the specialty.

Korean and Oriental Medicine

Korean medicine is a traditional East Asian system that relies on herbal medicine, acupuncture, or cupping therapies. Traditional medicine is widely used in Korea; it is officially recognized and regulated in the same way Western medicine is. Professional education in traditional medicine is structured similar to professional education in other medical programs: Practitioners must complete a six-year undergraduate or four-year graduate-entry program before taking a national licensing exam. Specialty training involves a one-year internship and three years of residency training. Credentials awarded include the Bachelor of Oriental Medicine or Doctor of Korean Medicine.

Teacher Education

Teaching is a well-respected and highly paid profession that is tightly regulated by the Korean government. Teacher training is provided by universities of education, colleges of education, and departments of education at regular universities. The Korean government sets national curriculum standards.

While preschool teachers can teach with an associate degree from a junior college, elementary school teachers must complete a four-year program at a dedicated public university of education or the private Ewha Womans University. Curricula include education in the subjects that students intend to teach, pedagogical subjects, and a teaching practicum of nine to 10 weeks. Secondary school teachers have a greater variety of study options and can study at departments of education at regular universities where programs also require a thesis. After completing the study program, candidates are eligible to obtain a Grade II Teacher Certificate, but must pass a comprehensive governmental employment examination if they want to teach in public schools. After three or more years on the job, teachers must complete an additional 180-hour training program to earn a higher-level Grade I Teacher Certificate. To ensure quality standards, further in-service training programs are provided on a continual basis, performance in which is tied to promotion and pay rates.

WES Document Requirements

Secondary Education

- Photocopy of graduation certificate or diploma issued in English—submitted by the applicant

- Academic Transcript issued in English—sent directly by the institution attended

Higher Education

- Academic transcript issued in English—sent directly by the institution attended

- For completed doctoral programs—a written statement from the awarding institution indicating the date of degree conferral and the major

Sample Documents

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Certificate of Graduation from High School

- Associate Degree

- Bachelor of Arts

- Doctor of Medicine

- Master of Science

- Doctor of Philosophy

1. International enrollments as a percentage of the total tertiary enrollment in the country as reported by the UIS.

2. When comparing international student numbers, it is important to note that numbers provided by different agencies and governments vary because of differences in data capture methodology, definitions of “international student,” and types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). The data of the UNESCO Institute Statistics provides the most reliable point of reference for comparison since it is compiled according to one standard method. It should be pointed out, however, that it only includes students enrolled in tertiary degree programs. It does not include students on shorter study abroad exchanges, or those enrolled at the secondary level or in short-term language training programs, for instance.

3. See: Ministry of Education: Globalization of Korean Education – Education in Korea, 2017, Sejong, pp. 48-53. (Link)

4. Ibid.

5. By some accounts, the percentage of foreign instructors among Korean faculty increased from 2.4 percent in 2000 to 7.1 percent in 2013.

6. Korean National Development Institute: A Window into Korean Education, 2017, p.22. (Link).