Education in Sri Lanka

Justine D’Souza, Credential Analyst, WES, and Thomas D. Moore, Credential Examiner, WES

This education profile describes recent trends in Sri Lankan education and student mobility, and provides an overview of the structure of the education system of Sri Lanka. This article replaces an earlier version by Nick Clark, and has been updated to reflect the most current available information.

Introduction

Sri Lanka won its independence from Great Britain in 1948, and enshrined the right to a free education in the constitution some 30 years later. Despite the ravages of a 27-year civil war that began in 1983 and ended in 2009, the country maintains some of the highest literacy rates in South Asia.

It also performs well on other educational indicators, for instance elementary school enrollment, and mean years of schooling. Public secondary and higher education studies are free to all citizens, though those living in regions still in recovery from the civil war may have less access to quality education than those living in other regions. Regardless, Sri Lanka has the highest reported youth literacy rate in South Asia at 98.77 percent, as compared to 89.66 percent in India, and 83.2 percent in Bangladesh. Along with the Maldives, Sri Lanka is one of only two countries in South Asia recognized by the UN as achieving “high human development.”

Since the end of the war, Sri Lanka has obtained substantial support from international aid organizations to improve its education system. In 2017, for instance, the country obtained a USD $100 million World Bank loan to expand STEM enrollment and research opportunities at the tertiary level, and to improve the quality of degree programs.

A Deeper Look: The Sri Lankan Civil War

Conflict between the ethnic Sinhalese majority, which makes up approximately 75 percent of the population, and the Tamil minority (approximately 11 percent of the population in 2012) simmered throughout the British colonial period (1815-1948) and long after independence, finally culminating in the Sri Lankan Civil War in 1983. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) became the Sinhalese government’s main opponent, after dominating several other Tamil minority separatist groups originally involved. The war ended in 2009 when the Sri Lankan government killed the LTTE’s leader. According to BBC, the death toll at the end of the war was about 70,000. Other estimates, including those from the United Nations (U.N.), put the toll as high as 100,000.

The conflict displaced hundreds of thousands of citizens, destroyed parts of Sri Lanka’s educational infrastructure, and led to a scarcity of teachers, teaching materials, and more. The war and post-war reconstruction efforts also diverted funds away from education. Educational resources remain unevenly dispersed, and reform efforts inconsistently implemented. Other legacy problems remain as well: Language policies, for instance, have reportedly been used as a means of restricting access to education. And although lack of academic freedom is not a substantial issue, Freedom House, an independent, global watchdog organization, has as recently as 2017 documented “occasional reports of politicization in universities and a lack of tolerance for dissenting views by both professors and students, particularly for academics who study Tamil issues.”

By most accounts, the human rights situation in Sri Lanka improved noticeably after the surprise election victory of Maithripala Sirisena of the oppositional Sri Lanka Freedom Party in 2015’s presidential election. Since the election, President Sirisena has, for example, authorized a long-blocked United Nations’ investigation into war crimes during the civil war, and supported a range of anti-corruption measures. According to Freedom House, Sri Lanka has experienced significant “improvements in political and civil liberties under the new administration.”

Outbound Student Mobility

Sri Lanka has a significant diaspora tradition, with large numbers of Sri Lankans living and working abroad either as skilled or unskilled professionals, mainly in Canada, France, India, and Australia, as well as throughout the Middle East. As one 2014 Australian government report notes, in Sri Lanka “a strong local culture of migration has developed whereby migration – especially international migration – is entwined with prosperity; migration is seen as a normal way to improve one’s economic situation or a means to navigate a crisis.”

Many Sri Lankan youth reportedly view migration or international schooling as an opportunity to enhance their employment prospects, and Sri Lanka’s tertiary-level student population is quite mobile – in part because higher education in Sri Lanka has insufficient capacity to address student demand, especially at the undergraduate level. According to a 2013 University World News report, Sri Lanka’s 15 state universities admit “only 23,000 students … annually, out of the 220,000 who sit the university entrance (A-Level) examination every year.” That same year, some 12,000 Sri Lankan students reportedly sought university education abroad.[1]Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies.

Sri Lanka’s government promotes this interest in study abroad: The country’s Ministry of Higher Education supports outbound mobility via program- and country-specific study abroad scholarship opportunities at the undergraduate and postgraduate level. Outbound mobility is generally expected to increase in the future, given the country’s robust economic growth, capacity constraints in higher education and demographic pressures (almost 40 percent of Sri Lankans are under 24 years of age). That said, countervailing factors – especially government support for an increase in the number of private and transnational higher education providers in the country, may alleviate capacity issues and impede that growth at least somewhat.

Australia is the leading destination for outbound tertiary-level Sri Lankans seeking degrees by a significant margin.[2]Australia has positioned itself as an ideal destination for international students through several mechanisms, including streamlined visa processing arrangements, expansion of the 20 hour to 40 hour work week for international students, and post-study work visas. The country has a strong draw among students from across South and Southeast Asia, and actively recruits students from Sri Lanka. Australia may also attract more students due to Brexit and the United Kingdom’s more restrictive immigration policies. Of some 17,790 degree students abroad in 2016, some 4,403 were pursuing degrees in Australia, according to data available from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS).[2] The second and third highest numbers of outbound tertiary-level Sri Lankan students, (2,797 and 2,507) were pursuing higher education in the United States and the United Kingdom, respectively. UIS data show that India and Malaysia attracted more than one thousand degree seeking students each.

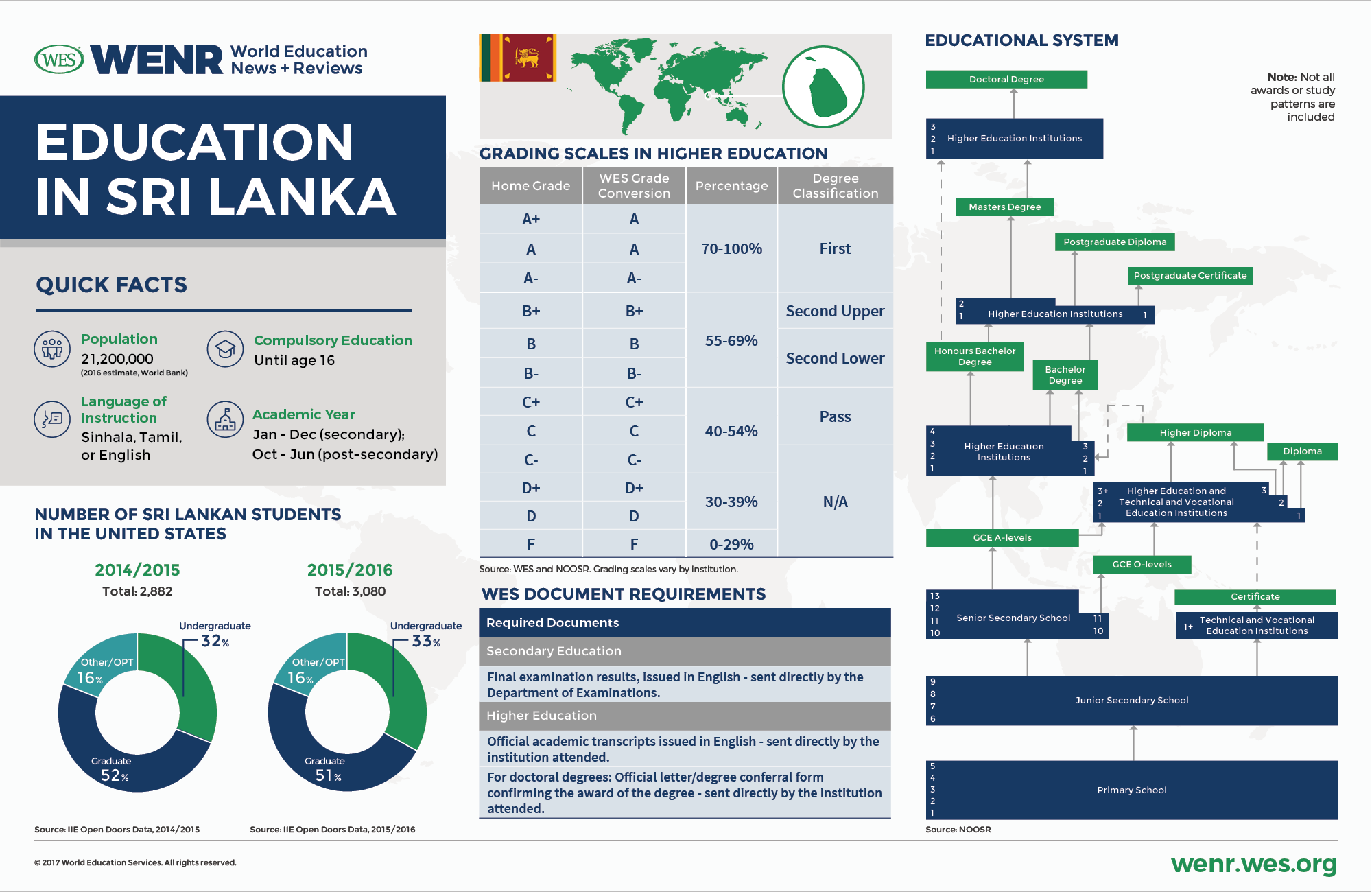

The United States has in 2015/16 seen a robust 6.9 percent increase in the number of inbound Sri Lankan students, a notable upsurge after declining enrollments in recent years, when the number of Sri Lankan students dropped by 1.2 percent (2014/15) and 4.2 percent (2013/14), respectively (IIE, Open Doors). According to the U.S. Embassy in Sri Lanka, “fifty percent of Sri Lankan students studying in the United States are pursuing graduate degrees up to the doctoral level, while 16 percent are engaged in post-degree Optional Practical Training, which allows international graduate students in the STEM fields to engage in professional training for up to 29 months following graduation.”

Canada is presently the ninth most popular destination for international degree students from Sri Lanka (UNESCO), even though total numbers remain small. Out of 17,790 Sri Lankan students abroad, 354 were studying in Canada in 2016. Partnership programs may make the country a more appealing destination in years to come, however. In 2015, the University of Calgary, for example, set up partnerships with the University of Moratuwa and University of Peradeniya in Sri Lanka, including scholarships for bi-directional educational exchange. The University of British Columbia, Carleton University, Concordia University, University of Guelph, McGill University, Ryerson University, University of Toronto and York University have recently also toured in Sri Lanka to promote their programs and recruit international students.

Inbound Student Mobility

The number of inbound students to Sri Lanka is small. Only 986 degree students for other countries were on Sri Lankan campuses in 2016, the highest number from Myanmar (348) and Bhutan (157).

The Sri Lankan government, however, has ambitions to join other Asian countries in becoming a more significant education destination, at least regionally. In 2014, the government announced plans to, as The PIE News framed it, “open up its higher education system to private overseas investors” as part of an effort to “attract 50,000 international students and 10 foreign university campuses by 2020.” Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Higher Education hopes to transform the country into the “most cost-effective and quality higher education hub in Asia”, and has substantially increased the number of student seats and scholarship opportunities for incoming international students since 2011.

Universities have also stepped up efforts to attract students from abroad. In 2014, the University of Colombo, the oldest Sri Lankan university, joined the newly formed Asian Universities Alliance to promote educational mobility within the Asia region, and to attract greater numbers of Asian students and professors, currently drawn to Western universities.

How the country will fare in these efforts is an open question. One 2012 World Bank Report listed Sri Lanka’s advantages as “the possibility of education in the English medium, modest prices, and positive government policies,” while also noting that international students may encounter weaknesses in the Sri Lankan education system, including “recurrent strikes, insufficient information on quality, and a limited reputation for academic research.”

The Education System in Brief

The British colonial period lasted from 1796 to 1948, and shaped the development of Sri Lankan education. Until the 1960s, for instance, all university instruction was conducted in English. And until this day, school examinations and curricular content remain modeled on the British examinations of the same names – the GCE O-Levels and A-Levels.

Children in Sri Lanka start school for the first time at the age of 5 and are required to stay until the age of 16. Languages of instruction include Sinhala, Tamil, and English.

The Country’s education system has undergone a number of reform efforts over the past 70 years. According to the Ministry of Education, Sri Lanka enacted “comprehensive education reforms” in 1947, 1960-61, 1972, 1981, 1997 and 2006. Most of the reforms are summarized below:

- 1947: Introduction of free education from Kindergarten to University

- 1961: Governmental take-over of denominational schools to establish a national system of education

- 1972: Attempt to make secondary education content more applied by adding a mandatory pre-vocational course at the junior secondary level. The reforms also sought to distance Sri Lanka from the British education system by renaming Ordinary level (O-level) and Advanced level (A-level) secondary examinations and “localizing” the content. Science, social studies, and mathematics courses were introduced for students in all streams. Eventually, however, the government reintroduced O- and A-levels, and made the pre-vocational course optional after popular criticism.

- 1981: Reform proposal to decentralize educational administration and create “cluster schools” to pool resource-poor schools with schools with more resources.

- 1985: Establishment of National Institute of Education

- 1986: Establishment of National Colleges of Education

- 1987: Devolution of power to provincial councils

- 1991: Establishment of National Education Commission [for teacher training]

- 1997: Reforms included a “four pronged strategy” to modernize curricula and textbooks, teaching methodology, distribute funds to improve school facilities, and provide management training to school principals. The reforms also involved revising exams to bring them on par with “developed countries”.

- 1998: Enactment of compulsory education regulations

- 2006: Education Sector Development Framework and Programme (2006-2010) – a UN-funded initiative to improve flexibility in internal management, enhance transparency, prioritize communal needs and increase efficiency in the utilization of school resources.

Elementary and Secondary Schools: Administration

The Ministry of Education directly administers education for schools designated as national schools (353 schools in 2016). The minister in-charge leads the Ministry of Education and is responsible to the President and cabinet members who oversee education.

Provincial councils oversee provincial schools. Each province has a provincial Ministry of Education governed by a designated Minister of Education and assisted by a designated Provincial Secretary of Education. In terms of quality of education and consistency of student outcomes, provincial administration is an area of concern. While national schools under the central government maintain standards for teachers and academic programs, provincial councils regulate education policies in a more decentralized manner. This has led to inconsistent curricula of variable quality in some provinces, and questions about whether or not students are prepared to enter the workforce if they cannot pursue further studies.

According to a 2013 report by the Ministry of Education, there are 9,931 government schools offering free education in Sri Lanka, as well as 98 recognized private schools, many of which are fee-based international schools. Sri Lanka also has 560 “Pirivenas,” or Buddhist centers that mainly focus on monastic studies. In 2016, over 1.7 million elementary school-aged children were enrolled in a government school, representing roughly 27 percent of the population under 18. Sri Lanka has achieved almost universal elementary school attendance, youth literacy rates, and gender parity in schools.

Most government schools provide elementary and secondary education at the same location. Only four percent of schools in Sri Lanka are exclusively secondary education institutions. At the secondary level, the government provides textbooks, and uniforms to students and also offers other welfare benefits, such as subsidized transportation and health services, to help students from disadvantaged families.

At the same time, educational quality is impacted by comparatively low levels of education spending. Sri Lanka’s education spending stood at 2.1 percent of GDP in 2015 (World Bank), and represented 7.3 percent of all government spending in 2014. This is below the spending levels in other South Asian lower-middle-income countries like India and Pakistan, where education expenditures amounted to 3.84 and 2.5 percent of GDP in 2013, respectively (World Bank).

Quality concerns, as well as overcrowding in competitive urban schools, have recently also spurred increasing demand for education in Sri Lanka’s growing number of private schools. While the private sector remains relatively small, and private school attendance is mostly limited to wealthier segments of society in urban centers, the overall number of recognized private schools has almost tripled from 37 in 1983 to 98 today. Private international schools are viewed as a good way for Sri Lankan students to prepare for study abroad, but depending on the type of curriculum taught, may not always provide for admission to public universities in Sri Lanka, which require A-Levels and may not recognize international school credentials, such as the International Baccalaureate. As in other countries, quality of the private sector can be uneven.

Higher Education: Administration

The Sri Lankan Ministry of Higher Education is a division of the larger Ministry of Higher Education and Highways. However, the Ministry is only directly in charge of two universities and one institute. Most administrative tasks in higher education are instead delegated to the University Grants Commission (UGC), an organization under the Ministry whose official functions are to “plan and coordinate university education, allocate funds to Higher Educational Institutions, maintain academic standards, and regulate the administration of and admission of students to HEIs.”

The UGC oversees 15 universities, and 18 institutes, and recognizes degree programs at a number of public and private institutions. It also sets minimum admission requirements for students. (These are described in greater detail below.) Under the UGC, the Quality Assurance and Accreditation Council is responsible for the accreditation of public and private universities. The board is made up of representatives from universities, the Ministry of Higher Education, and officials from the UGC itself.

Higher education institutions under the University Grants Commission are required to adhere to a regional quota system.

- Admission policies vary by discipline, but in many fields 55 percent of admitted students must have studied for the last three years in the district in which the institution is located.

- 40 percent of seats are allotted for “all-island” students, i.e. those who have studied in another of Sri Lanka’s 25 districts.

- An additional five percent quota is normally reserved for students from one of Sri Lanka’s 16 economically disadvantaged districts.

In addition to the institutions under the Ministry of Higher Education and the UGC, higher education is administered by other governmental institutions in Sri Lanka. For instance:

- The ‘General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University’ falls under the purview of the Ministry of Defense.

- The Ministry of Vocational & Technical Training and Ministry of Skills Development and Vocational Training run the ‘University of Vocational Technology’ (UNIVOTEC) and the Ocean University of Sri Lanka, respectively.

- The Aquinas College of Higher Studies is registered with the Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission of Sri Lanka.

Technical and Vocational Education

The Sri Lankan government recognizes the need to increase the employability rates of youth, a group that experienced an unemployment rate of 20.6 percent in 2015. (For comparison’s sake, only about four percent of the general population, including youth, was unemployed in 2015.) To that end, two ministries – the Ministry of Skills Development and Vocational Training and Ministry of Youth Affairs are tasked with providing technical and vocational training to prepare youth and young adults for careers in a wide range of occupational fields. (Specific fields, oversight authorities, and requirements are discussed below.)

The Educational Ladder

Elementary Education

Sri Lanka’s elementary education system starts with grade 1, and ends with grade 5. Boys and girls in Sri Lanka are mostly schooled together, although some single-sex schools exist. Entrance to elementary school is usually based on a student’s place of residence.

Elementary school students across the island follow a national curriculum that consists of six subjects; first national language, second national language, English, Mathematics, Religion, and Environment (a combination of social, biological, and physical sciences). These subjects are mixed in with non-academic activities such as play. However, desk work is gradually increased each year from grades 1-5.

At the end of grade 5, students have the option of taking a scholarship examination to gain entry to a prestigious national secondary school.

Secondary Education

Junior Secondary Level

Students attend the junior secondary level of schooling between grades 6 and 9. Students undergo coursework in the first language, English, a second national language, mathematics, religion, history, science and technology, health and physical education, practical and technical skills, social studies, life competencies and aesthetic studies. Progression is based on exams at the end of each school year. As in elementary school, entrance to junior secondary school is usually based on a student’s place of residence. The exceptions are children who, at the end of grade 5, win scholarships to national schools, and those who attend private schools.

Senior Secondary Level

Students attend the senior secondary level of schooling between grades 10 and 11. Admission to upper secondary school is extremely competitive with fewer places than interested students. Though students do not pay for schooling at the secondary level, many pay for private tutoring and prep courses so they can succeed on their General Certificate of Education (GCE) exams.

According to the Ministry of Education, the curriculum consists of “six core subjects and three or four optional subjects.” Mandatory subjects include first language, second language, math, science, history, and religion. Other subjects can include civics, art, dancing, entrepreneurship, commerce, agriculture, etc.

Grade 11 culminates in the award of the General Certificate of Education, Ordinary level (GCE O-Level). Students who pass their exams in their first language, mathematics, and three other subjects at higher or the same level of credit can proceed to the GCE, Advanced level stage. According to a 2013 report by the Ministry of Education, about 60 percent of students pass O-Levels and move on to A-Levels. The rest pursue vocational education or go directly into the labor market.

Collegiate Level (GCE A-Level)

The collegiate level, or GCE A-Level, lasts two years and is the prerequisite for entry into tertiary education. Students can chose to study in science, commerce, arts, or technology streams, and elect three corresponding subjects. The final A-Level examinations cover these stream-related subjects, as well as an English language exam, and a general paper.

If students do not qualify for university-level study after sitting for their exams, they may be eligible for admission to non-university higher education institutions that offer programs in “technology, business studies, and professions such as teaching and nursing.”

Higher Education

Admissions

Sri Lanka’s university admissions process is highly competitive. In 2012, about 60 percent of students passed the GCE A-Level examinations. Of this group, only about 17 percent were admitted into a university-level institution, according to the UGC. Minimum admissions requirements at universities include a minimum mark of 30 percent on the general paper, as well as passing grades in all three stream-related subjects in one test sitting. Students are ranked and admitted in accordance with a standardized scoring system based on their A-Level examination results.

For the few students who make it to university in Sri Lanka, the Ministry of Higher Education offers various scholarship opportunities to offset the price of school supplies and other related expenses. Recently, the Ministry implemented a “laptop loan scheme” that provides university students with interest-free loans to purchase laptops up to around USD $500.

Enrollment and Graduation Rates by Sex (HEIs under the UGC)

In 2015, there was a 40:60 male-female ratio amongst undergraduate students. That same year, 68 percent of university graduates were female. On the graduate level, 56 percent of students enrolled were women, and 49 percent of that year’s graduates were women. While women are more educated than men at the undergraduate level, and almost equally educated at the postgraduate level, this fails to translate into more jobs for women, especially for positions of power. In 2016, 8.5 percent of women were unemployed, compared to 3.4 percent for men. In 2016, only 6 percent of the seats in the national parliament were held by women.

Private Higher Education

Given the capacity shortages at public universities, the number of private higher education providers in Sri Lanka is growing. The Ministry of Higher Education can grant private institutions degree-awarding authority or program-based recognition, and the UGC currently lists 11 non-state institutions with degree-granting status on its website, as well as 6 non-state institutions with recognized programs. Total enrollments at non-state institutions are said to have reached roughly 69,000 students as of 2014. Admission to private institutions is typically based on A-Level examination results, although admission standards may be less rigorous than at public universities.

In addition to recognized private institutions, there are a number of unregistered providers, which avoid the lengthy and costly recognition procedures stipulated by the government by taking advantage of a regulatory loophole that allows them to operate by seeking affiliation with foreign universities. Under current law, affiliated institutions can freely enter franchising and validation agreements to offer degree programs in partnership with foreign providers, although the UGC does not recognize the final degrees awarded by foreign institutions. In 2015, a reported 4,518 students were enrolled at unregistered higher education institutions, most of them in business-related programs.

Such tertiary-level private education is controversial. In 2017, thousands of students, trade unions, and government doctors participated in protests against the South Asian Institute of Technology and Medicine (SAITM), Sri Lanka’s only private medical school. At the request of the government, SAITM suspended new student enrollment in May while awaiting a Supreme Court decision that will determine if graduates of the institute can be awarded medical degrees. (See additional detail below.)

This is not the first time that the Sri Lankan government has scaled back private education initiatives after protests. When it tried to legitimize private education in 2013, the related legislation faced significant protest from teachers and students. Protesters felt that the government should invest more resources into public education rather than relegating education to the private sector, especially as that might mean an erosion of free education.

Open and Distance Learning

In 2003, the Ministry of Higher Education initiated the Distance Education Modernization Project with a $60 million grant from the Asian Development Bank. The project aimed to expand distance education, including online education, and upgrade the capabilities of the Open University of Sri Lanka (see sidebar). Since then, there has been a significant increase in the number of online programs offered in Sri Lanka, even though the resulting gain in tertiary enrollments rates was by 2013 still below the expectations of the ministry, attributable to the fact that online degrees are not yet held in the same regard as traditional degrees. In 2015, 345,744 domestic students were enrolled in distance education programs, while just 125,121 students were enrolled in traditional programs across all universities and institutes under the UGC.

The Open University of Sri Lanka

The Open University of Sri Lanka is the only university in the country that provides open and distance learning education at all academic levels, from short-term certificate programs to Ph.D. degrees. Spread out across eight regional centers and 18 study centers throughout the entire island, the institution’s programs typically cater to working professionals who may have difficulty attending courses in a traditional setting. In 2015, over 38,000 students were enrolled at the Open University, making it by far the largest higher education institution in Sri Lanka in terms of the number of students. Between 2003 and 2015, the Open University experienced an increase of almost 62 percent in enrolled students, and the UGC plans to further increase enrollments by 5 percent annually.

Degree System

Undergraduate Education

Sri Lankan institutions offer a range of diploma and bachelor’s degree programs that are defined in Sri Lanka’s Qualifications Framework (SLQF). General bachelor’s degrees, such as the Bachelor of Arts (BA) or Bachelor of Science (BSc), are pegged at level 5 of the SLQF and require three years of full time study (90 credits) after the A-Levels.

Four-year honors degrees, also known as “special degrees”, on the other hand, are pegged at level 6 of the SLQF and require four years of study (120 credits). At least one year of study (30 credits) needs to be completed at advanced level, and the fourth year often involves research or a dissertation. Graduates with a high grade point average may, under certain conditions, be eligible for admission to doctoral programs. Degrees like the BA (Honours) and BSc (Honours) can also be earned via one-year programs following a 3-year general degree.

Also offered at the undergraduate level are a range of diploma programs, including one-year National Diploma (SLQF level 3) and two-year Higher National Diploma programs (level 4). These programs typically have a more applied focus, but may be transferred into bachelor’s programs, depending on the program.

Graduate Education

There are a number of different types of master’s degrees offered in Sri Lanka. Course work-based programs of one-year duration (30 credits, SLQF level 9) typically do not require a research component beyond some credit requirements related to independent study. Two-year master’s degrees (level 10), on the other hand, usually involve a minimum of 15 credits in independent research and include courses in research methodology, in addition to other coursework. Admission requirements for level 8 programs are stricter than for level 7 programs and may require a bachelor’s degree with a minimum GPA of 3.0.

Master of Philosophy degrees (level 11) are research degrees of two year duration that do not require course work. Admission is usually based on an honors bachelor’s degree (or a postgraduate diploma). Holders of Master of Philosophy degrees, as well as holders of level 10 master’s degrees, can enroll in doctoral programs of three-year duration, at minimum. The most commonly awarded degree is the Doctor of Philosophy, a terminal research degree earned by research and dissertation, although some programs also require coursework.

In addition to master’s and doctoral degrees, universities also award non-degree graduate level credentials, including postgraduate certificates (at least 20 credits, SLQF level 7) and postgraduate diplomas (at least 25 credits, SLQF level 8). These programs are typically designed to provide further specialization in more professionally-oriented disciplines, but may also be awarded as exit qualifications in incomplete master’s programs.

Professional Education

Accounting

The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka is the only institution in Sri Lanka authorized to certify Chartered Accountants. Students are required to complete a three-year professional training program after the A-Levels, culminating in the Chartered Accountant examination. After passing of the exam, students must complete practice requirements of at least three years before being granted Membership of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka, which entitles to practice as a Chartered Accountant. The institute also offers three- and four-year Bachelor of Science in Applied Accounting degrees, which are recognized by the UGC. However, a bachelor’s degree in accounting is not a prerequisite to becoming a Chartered Accountant in Sri Lanka.

Architecture

To become a Chartered Architect in Sri Lanka, students must follow the educational path mandated by the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects. Architecture students must complete a first degree program in architecture, typically a 5-year program leading to a Bachelor of Architecture after the A-Levels, or a 3+2 pathway leading to a Master of Architecture/Master of Science in Architecture following a bachelor’s degree. Graduates can apply for registration as a Chartered Architect after two additional years of professional practice.

Dentistry

The only faculty of dentistry in Sri Lanka that offers both initial first degree programs, as well as postgraduate education is located at the University of Peradeniya, which awards a Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) degree. The BDS program is entered on the basis of A-Levels and, until recently, used to span four years, consisting of two years of classroom instruction, followed by two years of clinical training at the institution’s dental teaching hospital. However, since 2015/16 the university has extended the curriculum to five years to include additional subjects, such as management and communication skills.

A dental auxiliary training school also trains students in dental auxiliary occupations, such as dental nurses and dental technicians. Students at this school can pursue a Diploma in Dental Assisting or a Higher Diploma in Dental Technology.

At the postgraduate level, dental education is offered at a number of institutions. Both the University of Peradeniya and the University of Colombo, for example, offer a range of programs in graduate dental specialties (orthodontics, oral surgery, restorative dentistry, community dentistry, etc.), including master’s and doctoral degrees.

Law

The standard professional degree of law in Sri Lanka is the Bachelor of Laws (LL.B). The Sri Lanka Law College offers a three-year LL.B. program to A-Level holders who pass its rigorous entrance examination.

Other options include four-year programs at the University of Colombo and the Open University of Sri Lanka. All law students have to pass a final examination administered by the Sri Lanka Law College and complete a period of practical training before being admitted to practice law.

Medicine

The Bachelors of Medicine, Bachelors of Surgery (MBBS) is a five-year program following the A-Levels that is offered at various medical faculties in Sri Lanka. Upon graduation, students have to complete a mandatory period of practical training of at least 12 months and pass an examination in order to register with the Sri Lanka Medical Council, which authorizes them to practice medicine.

NOTE: The privatization of medical education in Sri Lanka is currently a controversial topic with critics charging that it will erode academic standards, while proponents argue that privatization could alleviate capacity shortages. Sri Lanka’s only private medical college, the South Asian Institute of Technology and Medicine (SAITM), established in 2008, is embroiled in controversy. SAITM graduates obtained the right to register with the Sri Lanka Medical Council in 2017 after the courts ruled in favor of a SAITM graduate of the institute filed a writ in 2015. However, from the government’s perspective, the issue of whether or not SAITM provides adequate medical training and should be allowed to grant MBBS degrees remains unsettled.

Teacher Education

Teachers are either trained at 19 national Colleges of Education overseen by the National Institute of Education (NIE) or in Bachelor of Education programs at Sri Lanka’s public universities. Elementary and lower-secondary school teachers must hold a Trained Teachers Certificate, which is a three-year program that is typically entered on the basis of A-Levels, and comprises of two years of class room instruction and one year of in-service teaching.

Teaching in upper secondary schools requires a Bachelor of Education degree, respectively a Diploma of Education or Postgraduate Diploma in Education, a credential earned upon completion of a one-year graduate program following a bachelor’s degree in another discipline.

Technical and Vocational Education (TVE)

Education programs in Sri Lanka’s TVE sector range from short-term certificate programs and apprenticeship training to bachelor’s degrees in applied disciplines. In 2009, Sri Lanka established a National Vocational Qualifications Framework (NVQF). While not all TVE credentials awarded in Sri Lanka fall within this framework, the most common qualifications within that NVQF are:

- National Certificates (NVQF 1 to 4): These entry-level programs typically have a strong practical focus and are concentered in crafts and trade fields. There is no clearly defined program length – programs offered in Sri Lanka range between a few months and three years, based on industry needs. Admission may be based on O-levels, even though some programs have no formal admission requirements.

- National Diplomas (levels 5 and 6): One and two-year programs typically offered in technical fields and trades, as well business-related fields like accounting or marketing, for example. Admission is typically based on O-levels or a NVQF level 3 or 4 certificate. The program length is clearly defined at 60 credits (one year) at level 5 and 120 credits (2 years) at level 6.

- Level 7 Bachelor’s degrees: Vocational Bachelor of Technology degrees (3 years, 180 credits) and Special/Honours Bachelor of Technology degrees (4 years, 240 credits) are awarded by the University of Vocational Technology (UNIVOTEC). The programs are designed to be entered on the basis of an NVQF level 5 qualification, while holders of a level 6 qualification may be granted exemptions.

A variety of organizations and institutions oversee a wide range of TVE programs in Sri Lanka. These include the:

- Department of Technical Education and Training (DTET): Under the purview of Ministry of Skills Development and Vocational Training, the DTET oversees 38 technical colleges offering various certificate and diploma programs in trades and crafts, such as automotive technology, for example, as well National Certificates and National Diplomas in business fields like accounting or marketing. Students over the age of 17, who have passed their O-level examinations, are eligible for enrollment, though many courses have an age limit of 29. Like all public education in Sri Lanka, courses are free, but only for full-time day students. Those who take evening and/or part-time certificate courses pay a fee of Rs.2000 (US$ 13) per year.

- Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission (TVEC): The TVEC accredits of large number of technical and vocational institutions, most of them small private training centers offering short-term career training certificates. Other programs offered at these institutions lead to National Certificates and National Diplomas.

- Vocational Training Authority (VTA): Comprising 224 rural vocational training centers, 22 district centers, and seven national training centers, the VTA was established in 1995 with the aim to provide TVET in rural parts of the country. According to the institution’s website, the VTA presently trains roughly 30,000 youth in 83 trades each year. Many of these courses are lower level qualifications that require trainees to have completed 9 years of schooling in order to pursue training in occupations such as baking, hair dressing or gem cutting, while other courses in fields like masonry or automotive technology require O-levels for admission. The VTA’s Diploma in Draftsmanship requires A-Levels.

- National Apprentice and Industrial Training Authority (NAITA): The NAITA offers around 150 apprenticeship training courses in 22 vocational fields across 25 district offices and four institutes. Many of these courses require O-levels for admission, but other courses are open to trainees who have only completed grade 8. Apprentices typically earn a modest salary while training at a work place and may have the opportunity to sit for national trade tests in a number of occupations. Trainees may also apply to obtain NVQF certificate-level qualifications.

Document Requirements

World Education Services requires the following documents from Sri Lankan students when they apply for a credential evaluation:

Secondary Education

- External examination results for the General Certificate of Education, O-Level and/or A-Level – sent directly by the Department of Examinations

Higher Education

- Clear, legible photocopies of all degree certificates issued in English – sent by the applicant

- Academic transcripts issued in English for all programs of study – sent directly by the awarding institution

- For doctoral programs without coursework: a letter confirming the awarding of a doctorate – sent directly by the awarding institution.

Sample Documents

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- General Certificate of Education (Ordinary Level) Examination

- General Certificate of Education (Advanced Level) Examination

- Bachelor of Science (General)

- Bachelor of Architecture

- Postgraduate Diploma in Education

- Master in Library and Information Science

- Master of Philosophy

- Doctor of Philosophy

References

| ↑1 | Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Australia has positioned itself as an ideal destination for international students through several mechanisms, including streamlined visa processing arrangements, expansion of the 20 hour to 40 hour work week for international students, and post-study work visas. The country has a strong draw among students from across South and Southeast Asia, and actively recruits students from Sri Lanka. Australia may also attract more students due to Brexit and the United Kingdom’s more restrictive immigration policies. |