Trends in International Student Mobility

Rahul Choudaha, Research & Advisory Services, Li Chang, Research & Advisory Services, WES

International student recruitment is becoming integral to the financial health of many institutions of higher education in the United States. The current environment of budgetary cuts and increasing global competition is forcing many institutions to become strategic and deliberate in their recruitment efforts. However, effective international recruitment practices are dependent on a deep understanding of student mobility patterns and student decision-making processes. The purpose of this research paper1 is to provide an in-depth understanding of the trends and issues related to international student recruitment and to help institutional leaders and administrators make informed decisions and effectively set priorities.

Context of International Student Mobility

According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS), international students are defined as those “who have crossed a national or territorial border for the purposes of education and are now enrolled outside their country of origin.” An annual report published by UIS reveals that the global mobility of students increased to 3.4 million students in 2009, up from 2.1 million students in 2002.

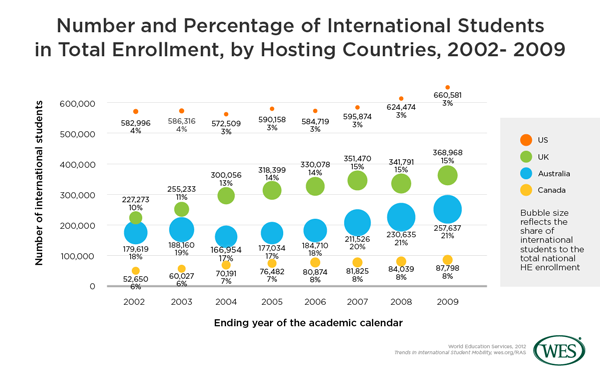

The four leading destination countries – the U.S., the UK, Australia, and Canada – all witnessed sizable growth from 2002 to 2009 (see Figure 1). Canada saw the biggest percentage gains, with enrollments increasing by 67% (from 52,650 in 2002 to 87,798 in 2009), followed by the UK and Australia with 62% (from 227,273 to 368,968) and 43% (from 179,619 to 257,637) respectively. Although U.S. enrollment grew at a slower rate of 13% (from 582,996 to 660,581 students), it remained the leading destination in absolute numbers and enrolled approximately one-fifth of all mobile students worldwide in 2009. The most recent data from the Institute of International Education (IIE, Open Doors 2011) showed an increase of 4.7% (from 690,923 to 723,277) in international student enrollment in the 2010-11 academic year compared to the previous year.

Despite the continued growth of international enrollments in U.S. postsecondary education, the country’s share of globally mobile students has been steadily declining over the last decade. As noted above, the U.S. claimed 20% of the world’s 3.4 million international students in 2009. However, due to increased competition and the opening of new markets, that share is in fact down from 27% in 2002, a detail that has been cause for concern for those in the U.S. who worry that the country might be losing its appeal among international students.

Nonetheless, the U.S. is expected to strengthen its leadership position due to the sheer size of its higher education system and institutional capacity when compared to competitor countries. The proportion of international students in the higher education systems of the UK, Australia and Canada is comparatively high, accounting for 15%, 21%, and 8% respectively, as compared to just 3% in the U.S. (see Figure 1).

In addition to the ability of a host country to absorb international students, a major factor in steering the global flow of international students is immigration and visa policies. In general, Canada currently embraces the most immigration-friendly policies and aggressive outreach efforts among major host countries, and has realized significant gains in international enrollments in recent years, whereas the increasingly stringent student visa requirements implemented in the UK could divert international students to other countries. Under such contextual change, the U.S., with a huge untapped potential for attracting international students, will likely see another year of international enrollment growth in 2012. However, the road ahead for most U.S. institutions of higher education will not be smooth as they grapple with challenges in meeting recruitment goals within limited time and budget constraints. This is where a better understanding of enrollment trends would help institutions in prioritizing their resources.

Source: Australia, UK, and U.S. data are retrieved from UNESCO Institute of Statistics using ISCED 5 & 6 standards. Due to missing data on Canada for 2009, we used Statistics Canada from 2002-2009. Definitions of level of study are different in the two data sources; therefore, differences may emerge.

International Enrollment Trends in the U.S.

Based on data published by multiple agencies and media coverage of institutional enrollment statistics, we have identified a few major international enrollment trends in the U.S, focusing on four themes: source countries, destination states, enrollment by academic level, and recruitment practices.

Source Countries

Undoubtedly, China and India are the two heavyweights with regards to outbound international student mobility. One in five of the world’s international students are from either China or India, with more than 700,000 tertiary-level students enrolled in a higher education system outside their home country. In the U.S. alone, these two countries contributed to 84% of all increases in international student enrollment between 2000-01 and 2010-11 (IIE, Open Doors 2011). However, China and India have been displaying a counter-trend over the last couple of years.

Recent statistics from the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (USICE) show that the number of active Chinese students on F-1 or M-1 visas at Student and Exchange Visitor Approved schools at the end of 2011 increased by about 28% to nearly 200,000 versus the year prior. The most commonly cited reasons for increased mobility among Chinese students are the growing supply of high school graduates whose families can afford a U.S. education and the unmet demand for high-quality education at home.

By contrast, enrollment growth among Indian students has slowed considerably, possibly due to the residual effects of the U.S. economic recession. However, there are signs that the slowing trend might be set to reverse. The U.S. Embassy in India reported in October of last year that the number of student visas issued to Indians in 2011 (October 2010 to September 2011) increased by 18% versus 2010 from 39,958 to 46,982, suggesting renewed interest in U.S. educational opportunities.

While China and India are too big to ignore, there are other emerging countries like Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, Mexico, and Brazil, for which recruitment efforts should also be cultivated. These should be explored not only for campus diversity purposes but also as a de-risking strategy versus an over-dependence on the Chinese and Indian markets. Brazil and Saudi Arabia are especially important due to the availability of government scholarships to students wishing to study in the U.S., which minimizes the prospective students’ dependency on institutional grant and financial aid. As the 2011 USICE data show, Brazil recently climbed into the list of top 10 countries supplying international students to the U.S., while Saudi Arabia became the fourth largest source of active students, increasing by nearly 50% compared to 2010.

Emergence of New Destination States in the U.S.

Growth in international student enrollment is not restricted to states traditionally hosting high international student populations like California and New York. With more aggressive institutional outreach efforts, states such as Delaware (+27%), Oregon (+19%), Arkansas (+18%), Alaska (+17%), and South Dakota (+15%) all saw impressive rates of growth from 2009-10 to 2010-11 (IIE, Open Doors 2011). The shift is driven by a new generation of international students who are considering a wider range of options, as well as by an increasing number of U.S. institutions that proactively recruit and enroll international students.

The emergence of new destination states may be attributed to state-level policy changes, too. Some states have initiated legislative changes to allow for the enrollment of more international students in public institutions. For example, public universities in Colorado can now recruit more international students because a state law capping the share of out-of-state students at one-third of total enrollment has been changed, according to a local newspaper report. The modified law excludes international students from the out-of-state cap, allowing public institutions to increase international enrollment.

Growth at the Bachelor’s Level and in ESL and Non-Degree Programs

In 2010-11, IIE data revealed that more than one-third of all international students in the U.S. were enrolled at the bachelor’s level, where the growth is currently outstripping that at the master’s and doctoral levels. The rising purchasing power and changing demographics in countries like China, India, and Saudi Arabia are likely to fuel the growth momentum further. For instance, IIE reported that in 2004-05, only 8,299 Chinese studied at the undergraduate level, accounting for 14% of all Chinese degree-seeking students in the U.S. Stunningly, by 2010-11 this group was seven times larger, translating to a total of 56,976 Chinese undergraduates making up 41% of all degree-seeking Chinese students in the U.S.

USICE data help confirm this trend, showing that the number of active international students at the bachelor’s level at the end of 2011 had increased by about 12% as compared to the previous year. Additional anecdotal evidence for fall 2012 applications suggests that the increase is likely to continue.

For example, recent application data released by the University of California (UC) shows that the institution has received a total of 13,873 freshman applications from international students for fall 2012, a 66.4% increase over last year. Among all UC campuses, Berkeley, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Santa Barbara each reported an over 40% increase in applications. Given current fiscal challenges and the longer stream of revenue from bachelor’s programs (four years) versus master’s programs (two years), institutions in the U.S. are likely to expand international recruitment efforts at the bachelor’s level, especially as these students are typically funded by their families and consequently less dependent on financial aid.

In addition to growth at the bachelor’s level, English as a second language (ESL) programs are also emerging as an important pathway for international students, most notably from Saudi Arabia. This trend is supported by current USICE data, which shows that the number of students participating in language training grew by 12% between 2010 and 2011.

There has also been significant growth in the number of students undertaking post-graduation work placements under the Optional Practical Training program in recent years. Given that at least 35% of all international students in the U.S. are enrolled in STEM fields (among students from India, two out of three are STEM students), this option is an important factor for students heading for the U.S., especially those coming from India.

Emerging Recruitment Practices

The number of international students enrolled in U.S. institutions of higher education is relatively low as a percentage of overall enrollment, while there continues to be an opportunity to leverage the attractiveness of the U.S. brand. This, when combined with university budget cuts from public coffers, means that many institutions are facing intense pressures to become more efficient in achieving their international and out-of-state recruitment goals. In this context, we have identified three emerging international recruitment models.

Firstly, partnerships with third-party service providers, such as commissioned agents and pathway programs are gaining prominence. However, the use of agents and expectations for quick turnarounds in enrollment numbers may be coming at the expense of quality. Australia, one of the pioneers of the agent model, noted such concerns in the recent Knight Review of the Australian Student Visa Program, stating that “regrettably the expansion of non-genuine student numbers was facilitated by some agents and institutions whose business practices were highly dubious, sometimes illegal” (para. 10). Therefore it is essential for institutions to create appropriate risk management practices to ensure that the integrity of their admissions processes are not compromised if using third-party recruiting agents.

Secondly, social media is an emerging and evolving channel that is quickly becoming indispensible to international student recruitment. International alumni are excellent resources, not only for student recruitment through referrals but also in terms of their future potential for fund-raising. Many institutions lose touch with international students once they graduate, but social media offers a cost-effective and credible way to connect alumni with prospective students (Choudaha, 2012)2.

Like any new practice, the use of social media in international recruitment poses several challenges and opportunities. However, institutions that embrace this change in an informed and entrepreneurial manner will create a significant competitive advantage. One example of a university using social media channels effectively is Brock University, which has created a public page at Renren, a Chinese social media network, to answer questions and connect with prospective students. According to feedback from students, they seem “to appreciate Brock’s accessibility, and its ability to communicate with them in their own language.”

Thirdly, a review by Australia Education International, the international arm of the Department of Tertiary Education, summarized that “ in the absence of a nationally coordinated U.S. outreach effort, the idea of state-wide initiatives has rapidly spread as a cost effective way for institutions to pool their resources and efforts and enable even smaller or less well-known colleges to reach students around the world”(p.17).

The lack of a federal recruitment strategy has prompted several states to act as collaborators with local institutions to attract international students. For instance, Ohio, currently the country’s 8th largest host state, saw a 10.5% increase in international enrollment from 2009-10, and some of this growth can be attributed to a variety of recruitment strategies and marketing campaigns employed at the state level.

Institutional Cases

Recruiting beyond China and India

To diversify international population, several universities in Ohio recruited students from less-sought-after countries. In 2011, Ohio Wesleyan University recruited its largest number of first-year international students from Pakistan and Vietnam.Source: OSU strives for global student diversity; The Columbus DispatchEmerging Destination States: Oregon

Several universities in Oregon including Oregon State Universities, Portland State Universities, and the University of Oregon, concurrently reported the largest-ever enrollment of international students: a total of 5,695 international students, up by 45% in 2011.

Source: Oregon universities open today with record international student enrollment

Growth at the Bachelor’s Level

The University of Iowa has witnessed its international students quadrupling in the past four years. The increase is especially pronounced at the undergraduate level, where 1,736 students enrolled in Fall 2010, a dramatic 350% increase over the 2006 count of 380, and a 35% increase from 1,283 in 2010.

Source: UI fall enrollment on par with last year; diversity increases;

Increase in UI international students is good for local economy | TheGazette

Growth of ESL Programs

Portland State University – One of the seven major universities in Oregon, PSU has seen a 3.4% increase in international student enrollment. The university adopted conditional admission practices and offers ESL programs to international students. The top source country for PSU is currently Saudi Arabia (428 Saudi Arabian students were enrolled in Fall 2011), the largest supplier of ESL students to the U.S.

Source: 10 U.S. Colleges With Highest ESL Participation Rates – US News and World Report

International student enrollment at all-time high | Portland State Vanguard

Recruitment with Social Media

Brock University reported “[s]ince September, 443 QQ users [QQ is a popular China-based instant messaging platform] have been interested in Brock, while 1,149 are interested in Brock on Renren. In March, Brock went from a personal to a public page on Renren, which allows it validation and a broader reach. Students seem to appreciate Brock’s accessibility, and its ability to communicate with them in their own language.”

Source: Brock uses China’s vast social media to recruit students | The Brock News

Conclusion

The year 2012 is expected to be another growth year for international student mobility worldwide, powered not only by traditional sending countries like India and China, but also by the movement of students from emerging markets such as Saudi Arabia and Brazil. International students will continue to display diversified choices of destination and will gravitate toward enrolling in English language programs and studying at the bachelor’s level. Furthermore, as and when the U.S. economy picks up momentum, the perception of improved employment prospects will strengthen among international students and the stringent immigration policies of the UK are likely to divert some traffic to the U.S. and other destinations like Australia and Canada.

Although student mobility is expected to grow, institutions have to compete hard for talented and self-funded students. Recruitment efforts are expected to be delivered in a shorter timeframe and with tighter budgets. This is where institutions need to experiment with emerging models like the use of social media in international recruitment. A deeper understanding of global mobility trends and their relationship to the applicant pipeline will help institutions channel their efforts. Institutions need to invest in understanding the decision-making process of their prospective students and monitor the effectiveness of their recruitment channels.

International student recruitment is an inherently complex, costly and competitive domain, which is becoming increasingly integral to the financial health of many institutions. Institutions that are strategic, deliberate and informed in their recruitment efforts will maximize the opportunities in an efficient manner.

1. This WENR article is a summarized version of the full research paper.

2. Choudaha, Rahul (2012). Social Media in International Student Recruitment, Association of International Education Administrators (AIEA) Issue Brief.