Best Practices: Strategies and Processes to Obtain Authentic International Educational Credentials

Introduction

Best Practices: Strategies and Processes to Obtain Authentic International Educational Credentials was developed in response to challenges for consistently assessing and recognizing international academic credentials and the subsequent barriers faced by skilled immigrants in using their education in Ontario, Canada. The guide is a result of teamwork and a consultative process in which representatives of Ontario regulatory bodies and World Education Services (WES) worked together to create guidelines on how to obtain authentic academic documents and develop alternatives to unavailable documentation. Although this guide was originally developed with the intention of informing Ontario regulators about common terminology and documentation practices, we believe that because inconsistencies with documentation practices and terminology abound in the field of credential assessment this will be a useful reference for sharing and promoting consistent practices and terminology across Canada and beyond.

The intention of this guide, therefore, is to advise on processes related to credential authentication and on any other documentation-related processes. The strategies and processes described in the guide apply to documents being received from any source; however, the particular focus is on international credentials (i.e. credentials issued by non-domestic institutions). Having reliable and consistent documentation practices based on authentic documents helps promote portability of documents and reduces the need for individuals to have documents sent and verified numerous times to different organizations and institutions.

Online copies of the full guide are available for free: Best Practices: Strategies and Processes to Obtain Authentic International Educational Credentials

Canadian Immigration Context

Canada has often been described as a nation of immigrants, and demographic realities suggest that it is becoming ever more so. Every year, approximately 280,000 permanent residents make Canada their home and about 20 percent of Canada’s population was born outside the country.1 In addition, immigrants coming to Canada are highly educated and skilled. Today, 70 percent of all recent working-age immigrants (15 to 65 years of age) have at least some post-secondary education and 20 percent have a graduate degree, while only 5 percent of Canadian-born do.2 Many skilled immigrants also intend to work in regulated occupations in Canada. Between 2004 and 2006 almost 32,000 immigrants aged 18 to 64 arriving in the province of Ontario indicated that they intended to work in a regulated profession or trade.3

Despite immigrants’ higher levels of education, almost 60 percent are not able to find jobs in their intended occupations.4 In 2006, the national unemployment rate for immigrants who had been in Canada five years or less was more than double the rate for the Canadian-born population,5,6 while 28 percent of recent immigrant men and 40 percent of women with a university degree held jobs which did not require a university education.7 The cost to the Canadian economy of failing to adequately recognize the skills and qualifications of immigrants has been estimated at between C$4.1 (US$4 billion) and C$5.9 billion (US$5.77 billion) annually,8 and up to C$15 billion (US$14.7 billion), since immigrants are working far below their skill levels and therefore not as economically productive.9

Challenges

When seeking entry to a profession or employment in Canada, internationally trained professionals often face multiple challenges. One of the most serious challenges to labor market success, as identified by immigrants themselves, is a lack of recognition of academic credentials earned outside of Canada. International credential recognition is a very complex process that depends on many factors, often combining credential evaluation with other processes such as language, competency and skills assessments.

In Ontario there are currently 37 professional regulatory bodies, a number of industry associations, 28 community colleges, and 21 universities; each holding their own distinct role and bearing on international credential recognition and evaluation. Most of the institutions and organizations responsible for international credential recognition function independently of one another, with credential evaluation and recognition processes and practices occurring within the organization. The lack of consistency in credential evaluation processes can be confusing for internationally trained professionals, and can lead to duplicate requests for the same documentation. In addition, organizations and institutions relying on their own standards and methodology – often not made available to the public – can sometimes be perceived as having processes for credential assessment and recognition that are biased and unfair.

When different institutions and organizations assessing academic credentials have varying documentation standards, portability of academic credentials becomes difficult and can be onerous on the individual. However, if all institutions and organizations involved in credential evaluation hold common documentation standards, it creates an environment for a more consistent authentication process, which in turn results in improved portability and recognition of international academic credentials. This can greatly reduce costs and time associated with obtaining documentation from abroad.10

Opportunities

In an ideal world, harmonization of credential evaluation and recognition processes would occur in all aspects of credential evaluation. However, it is important to acknowledge differences resulting from specific mandates and responsibilities placed upon organizations and institutions assessing and recognizing international credentials. As such, harmonization in selected areas may be a more effective strategy, and could begin with the standardization of authentication and/or verification of documents.

The Best Practices: Strategies and Processes to Obtain Authentic International Educational Credentials guide is the result of the hard work and dedication of the Documentation Standards Project Working Group, a group of Ontario regulators and representatives from WES Canada, who came together over an 18-month period beginning in 2008 to develop clear guidelines on how to obtain authentic international academic documents, suggest alternatives to unavailable documentation and harmonize evaluation and documentation terminology.

The purpose of the guide, therefore, is to move towards the goal of having common documentation standards by:

- Describing how to obtain authentic documents

- Suggesting documentation requirements criteria

- Providing definitions to the terms used in documentation practices

- Suggesting alternative documentation in situations where required documents are not available

What are Authentic Documents?

An academic credential is authentic when it is issued by a legal entity that is authorized to issue academic credentials and/or conduct examinations and/or teaching. The process of establishing the authenticity of an academic credential, therefore, begins by confirming that the credential in question was issued by an entity authorized to do so (Recognition of Institution Process). Once the legitimacy of the issuing authority/institution is established, the second step is to establish that the credential in question originates from the issuing authority (Document Authentication Process). This can be achieved by ensuring that the documents are received directly from the designated authority in a sealed envelope. The process of receiving official or verified documents is similar to the practice among North American institutions of sharing and receiving official academic transcripts directly.

Obtaining Authentic Documents

A common approach to the authentication process is to scrutinize documents for any warning signals such as noticeable inconsistencies, lack of safety features, awkward or forced lettering, misspellings, etc. This can be a very time consuming approach and has become impractical and less effective as technology has made the production of fraudulent documents fast, easy and inexpensive. This reactive approach aims to detect fraudulent documents that have already entered the system rather than preventing these documents from entering in the first place.

Rather than trying to detect fraudulent documents, adopting a credential authentication process that ensures that only authentic documents are entering the system is a more effective solution. It is important that the criteria upon which such an authentication process is built is clearly defined and can be easily communicated to all involved in the process.

Credential evaluators using the guide can incorporate what is feasible for their situation keeping in mind that “while the need to establish authenticity of documents as a part of the assessment procedure is very real, this need should nonetheless be balanced against the burdens placed upon applicants. The basic rules of procedure should assume that most applicants are honest, but they should give the competent recognition authorities the opportunity to require stronger evidence of authenticity whenever they suspect that documents may be forged” (The Lisbon Recognition Convention Committee, 2001).

This guide promotes the notion of using official documents as the most reliable evidence of an individual’s educational achievements and reviews the different types of documents and the degrees of reliability attributed to each document type:

- Verified Documents

- Official Documents

- Original Documents

- Certified/Notarized Copy

- Photocopy

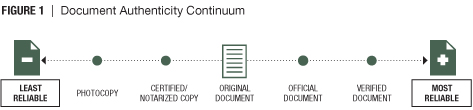

For illustration purposes, consider a continuum or a scale against which the methods of determining document authenticity could be measured, referred to here as the Document Authenticity Continuum. The right extreme of the continuum represents the most reliable type of documents used in the Credential Authentication process, and the left extreme represents the least reliable documents upon which the Credential Authentication process can be based. The full guide outlines considerations, good practices and common concerns, and good practices for each type of document.

Verified Documents

A Verified Document is a document that has had its authenticity confirmed through direct contact with the issuing authority and/or centralized agency authorized to verify academic credentials. Authorized officials at the issuing institutions must verify documents as authentic. Documents that are authenticated through the Verified Document process are deemed the most reliable.

Official Documents

An Official Document is the one that has been received in a sealed envelope directly from the issuing authority and has never been in the possession of anyone other than the institution that issued it. The Credential Authentication process is most reliable when the academic document is issued by a designated authority, has not been altered and has been transmitted securely to the intended recipient. Receiving institutions and organizations can consider the document official when these conditions have been met.

Original Documents

An Original Document is a document that was issued to an individual by the issuing institution.

The difference between an original and official document is in the mode of transmission. An official document has been transmitted directly from the issuing institution to the receiving institution. An original document was transmitted to an individual and handled by him or her first before it has reached the receiving institution. Therefore, an Original Document is a more reliable document in terms of determining document authenticity than a regular, certified or notarized photocopy but is less reliable than an official document received directly from the issuing institution.

Certified/Notarized Copy

Copies made by notaries (Notarized Copies) or other authorized persons, and certified true copies are still considered copies. A Certified (true) Copy is a photocopy of the original document attested to by an authorized person (i.e. authorized personnel at the embassy, department of interior affairs, etc.). A Notarized copy is a photocopy of an original document deemed to be a true copy of the original attested to by a notary public.

Photocopy

A Photocopied/Copied Document is one that has been copied by someone other than the authorities at the academic institution or the verifying official. Establishing authenticity of a copied document is harder than establishing that of any other document type.

Alternative Documentation Solutions

In most cases there are systems and ways to obtain authentic academic documents. However, in some rare instances, despite an individual’s efforts and the available assistance from the assessing organization or institution, some individuals may still find it impossible to obtain the required documents to support their application. Most institutions and organizations have developed alternatives for handling such applications. In most instances, assessing organizations will gather information from the individual about their circumstances first and then decide whether it is appropriate to apply an “unavailable documentation solution.”

The guide outlines a number of key considerations, other types of documentary proof, online verification and tools, competency testing and portfolio building as ways to support alternative documentation solutions.

Electronic Transcript Exchange

Electronic Transcript Exchange is a secure process allowing participating institutions and organizations to exchange authentic electronic transcripts and academic documents through a secure network. When agreed-upon protocols are in place, a system of Electronic Transcript Exchange can offer the following benefits:

- Faster delivery of academic transcripts

- Reduction in administrative expenses

- Easier tracking of incoming documents

- Reduction in paper use

- Reduction in the number of fraudulent documents in the system

The authentication process for Electronic Transcript Exchange remains concerned with identifying whether transcripts are received directly from the issuing institutions (mode of transmission) and whether documents have been handled by anyone other than the institution that issued them (presence of sealed envelope). Since documents are exchanged electronically, there is no “sealed envelope” per se and authorized senders and recipients are validated before a transcript is exchanged. All documents are encrypted and securely transferred electronically with transmission protocols between institutions and organizations designed to safeguard exchanged data. Any transcript transmitted outside of the Electronic Transcript Exchange would not be considered official.

Common Terminology

Given that terminologies in international credential evaluation are at times used inconsistently, a common credential evaluation glossary is included in the guide. Use of common terminology is essential in ensuring that all involved in credential evaluation understand each other and interpret criteria set by the Best Practice Model(s) in a consistent manner. Further, common use of terminology will make it easier for immigrants to understand the credential assessment procedures and policies.

Conclusions

By adopting a consistent method for receiving authentic international academic credentials, organizations and institutions assessing credentials can help ensure the integrity of the documents they receive while also reducing the risk of mistakenly accepting altered or fraudulent documents. Moreover, by adopting standard practices, institutions and organizations receiving documents are treating domestic and international documents fairly and are authenticating all documents in a consistent manner.

The full guide can be downloaded for free here: Best Practices: Strategies and Processes to Obtain Authentic International Educational Credentials

1. Statistics Canada, 2007, Immigration in Canada: A Portrait of the Foreign-born Population

2. Statistics Canada, 2007, Study: Canada’s immigrant labour market

3. Office of the Fairness Commissioner, 2007-2008 Annual Report,

4. Statistics Canada, 2004, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada: Process, Progress and Prospects

5. Statistics Canada, 2007, Study: Canada’s immigrant labour market

6. Zietsma, 2007, p. 15, The Canadian Immigrant Labour Market in 2006: First Results from Canada’s Labour Force Survey

7. Gilmore, 2008, The 2008 Canadian Immigrant Labour Market: Analysis of Quality of Employment

8. Bloom & Grant, 2001, p. 21, Brain Gain: The Economic Benefits of Recognizing Learning and Learning Credentials in Canada

9. Reitz, 2001, Immigrant Skill Utilization in the Canadian Labour Market: Implications of Human Capital Research

10. Lowe, World Education Services, 2009, unpublished