Nigeria: How Will the Economic Downturn Affect Outbound Student Mobility?

Nancy Keteku, Regional EducationUSA Advising Coordinator, Africa West & Central

Why is it that, as Nigeria’s economy heads downhill, students increasingly flock to expensive international destinations? Isn’t that counterintuitive? Not for a competitive, ambitious country whose citizens are inured to uncertainty at home. Against an often chaotic domestic backdrop, the challenges of academic life abroad may offer young, ambitious Nigerians far more reward than risk.

A developing country of 180 million people and a per capita income of $5,900, Nigeria is now officially in a recession. Sixty-two percent of the population lives in poverty. As of early 2017, the country continued to struggle through its “worst economic slump in 25 years.” Yet Nigerian students continue to forge paths in international education, and in significant numbers. Over the past four years, data from UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) shows a 44 percent increase in the number of Nigerian students seeking degrees from higher education institutions outside the country, to over 71,000 as of the most recent numbers published. (This compares to a 21 percent overall increase in the number of Sub-Saharan African students enrolled abroad, to 328,000.)[1]Based on a comparison of UNESCO Institute for Statistics data captured in 2012 and again in late 2016.

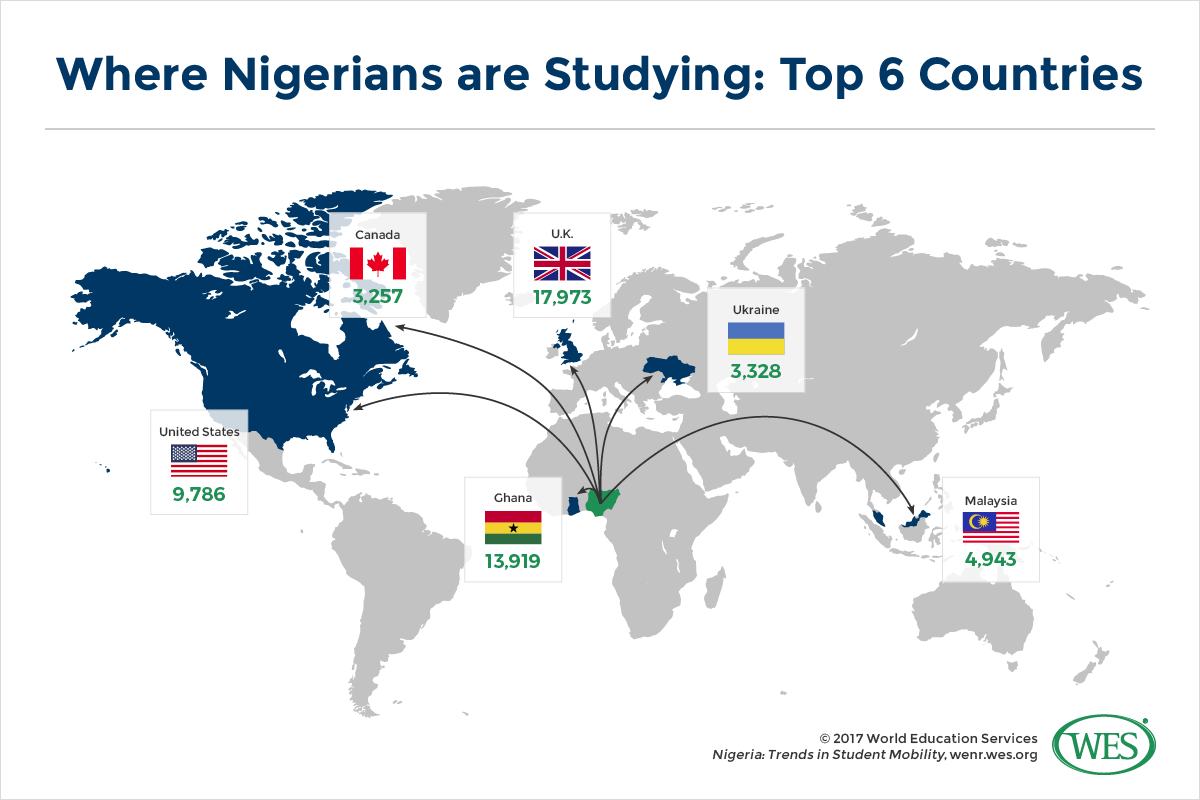

These students go everywhere: Nigerians are reported to be studying in more than 70 countries. In North America, the U.S. and Canada are both increasingly significant destinations. Per the latest Open Doors report from the Institute of International Education (IIE), “10,674 students from Nigeria were studying in the United States… in the 2015/16 academic year… (up 12.4 percent from the previous year).” [2]Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies.

According to Canadian governmental sources in both Nigeria and Canada, Nigerian enrollment in Canadian institutions rose 20 percent in 2015; the Canadian High Commission in Abuja reported 9,000 Nigerians studying in Canada, and the Canadian Bureau for International Education reported Nigeria as the eighth leading source of international students, with 8,620.[3]As of March 2017, UIS reports 3,257 Nigerian students in Canada. The discrepancy is likely due mostly (though not entirely) to the type of student mobility data captured. UNESCO UIS only captures degree mobility, i.e., students who have gone to a country to pursue an actual degree. Other agencies may capture credit mobility, i.e., students who study abroad for a semester, year, or summer and return home and apply the credits earned in that country to a degree in their home country institution. Still others, such as the Chinese Ministry of Education, also report inbound international vocational students toward their international student estimates.

What push and pull factors are behind these students’ mobility? This article examines the current political and economic situation facing Nigerian students, some of the reasons they push past those challenges, and the trends in their choices of education destination.

Outbound Student Mobility: The Economic and Political Context

Home to Africa’s largest population, Nigeria is e xpected to replace the U.S. as the world’s third most populous nation by 2050. Its economy has also been expanding in recent years, taking over the title of the continent’s largest economy in 2014. In 2015, the country passed a significant litmus test of democracy, with the first peaceful electoral transition of presidential power from one party to another since 1960, when the country first gained full independence from Britain. The 2015 election ushered in a new government, which pledged to stabilize the economy, root out corruption, and defeat violent extremism. However, a precipitous drop in oil prices in 2014-15 sent the economy into a tailspin, and implementation of promised reforms stalled out.

Nigeria is now beset by a groundswell of popular frustration, and, most recently, protests. Many families, especially the millions in Nigeria’s expanding middle class,[4]The African Development Bank’ defines middle class as people spending between $2 and $20 per day. By this definition, middle class Nigerians would have disposable income, but not necessarily sufficient resources to pay for university outside the country. According to the New York Times, “Standard Bank, a South African bank with branches across the continent, estimated that Nigeria’s middle class grew by 600 percent from 2000 to 2014. While 4.1 million Nigerian households are now considered middle class, or 11 percent of the total population, an additional 7.6 million households would make it into that category by 2030, according to the bank’s projections.” (From “Nigeria Goes to the Mall,” The New York Times, Norimitsu Onishi, January 5, 2016) have lost their sources of income in the ongoing recession. Reports of small business failures and public sector salaries that remain unpaid for months are common. For international students, the most disruptive development in 2016 was the Nigerian government’s decision to severely tighten access to foreign currency. The move sought to stop an estimated USD $2 billion annually in “capital flight” spent on international school fees, and to protect the dwindling reserves of the Central Bank of Nigeria. The impact on international students was profound. Nigerians were allowed to charge only $100 a month in foreign currency on their credit cards, so as to tighten the outflow of hard currency. Very few requests for outward transfer of tuition payments were approved; almost everyone had to change naira into dollars at the street rate, take the cash to the bank, and have it wire-transferred to the foreign university.

At the start of 2017, the official exchange rate was holding steady at just over 300 naira to the US dollar, but the “street rate” had passed 500 naira to the dollar. Funds can no longer be transferred out of the country by Western Union, Flywire, or other systems, even for payment of SEVIS fees associated with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Student and Exchange Visitor Program.

On February 20, 2017, the Central Bank of Nigeria threw a lifeline to parents of international students, issuing new regulations that permit the export of USD $30,000 per year in tuition plus USD $16,000 per year in travel allowance, at no more than 20 percent above the interbank rate. This will reduce the local currency cost of paying educational expenses by about 25 percent below what families were paying before February 20. Tuition funds will be wire-transferred directly to the school upon presentation of bills. Processing time is not yet known.

One Casualty of the Economy: Government-Funded Scholarships

In February 2016, ICEF Monitor reported that “by some estimates, as many as 40 percent of Nigerian students abroad have some measure of scholarship funding for their studies.” The recent downturn has diminished the availability of that funding. When the economic slump took hold in 2015 and 2016, most government scholarship initiatives were suspended, and delays in transferring payments for affected many students. In 2015, for example, Nigeria’s Rivers State Sustainable Development Agency (RSSDA) , which supported more than 1,200 Nigerian students abroad, suspended operations, leaving hundreds of students scrambling to cover tuition and other fees. The Nigerian government sought to honor commitments to institutions but few of these programs have been reinstated. The most prestigious scholarship, from the Petroleum Technology Development Fund continues to offer a limited number of graduate scholarships tenable in the United Kingdom, Germany, Brazil, France, and eight universities in the United States. However, as of this writing, such scholarships do not provide a reliable means of funding education abroad.[5]It should be noted that the availability of government-funded scholarships is subject to change.

Enrollment Destinations: New Patterns

Despite increased price sensitivity, economic uncertainty and diminished funds have not snuffed out Nigerian students’ academic aspirations or outbound mobility rates. The continued outward drive is likely due in no small measure to the lack of options at home: The nation produces some 1.5 million high school graduates each year. Only a quarter to a third can find placement in the country’s own institutions. The good news for the students is that, compared to the rest of Africa, Nigeria is a relatively mature market in terms of international education. Top graduates of Nigeria’s leading federal universities tend to be well-prepared for graduate study, and can competitive with their peers from around the world.

Nigerian trend watchers report that families in northern Nigeria remain closely aligned with old colonial ties, and often prefer study in the U.K., while families in southern Nigeria prefer the U.S. and Canada. The United States continues to be attractive, in large part because of the opportunities for partial or full scholarships that bring costs in line with those of other countries where higher education tends to be more affordable. However, less expensive study locales, whether in Ghana, Ukraine, or Malaysia, are also gaining favor.

The top six destination countries for outbound Nigerian students now include:

The U.K.: Despite a 10 percent decline in enrollment numbers between 2015/16 and 2014/15, the U.K. is still Nigerians’ top choice of academic destination, attracting some 16,100 students in the most recent school year. Old colonial ties continue to play a role in large numbers of Nigerian enrollments in the U.K., as does a common language.

The U.K.: Despite a 10 percent decline in enrollment numbers between 2015/16 and 2014/15, the U.K. is still Nigerians’ top choice of academic destination, attracting some 16,100 students in the most recent school year. Old colonial ties continue to play a role in large numbers of Nigerian enrollments in the U.K., as does a common language.- Ghana is Nigerian students’ second leading choice for higher education: The number of Nigerians reported studying in Ghana has more than doubled, to almost 14,000, in the past four years. The reasons for the rise are multiple, and include proximity, a long trade history, social ties, a common language, a common educational heritage, and a stable higher education system.

- The U.S. is the third leading destination for Nigerian students abroad. Between the 2014/15 academic year and 2015/2016, enrollments rose by 12.4 percent. Nigerians are the 14th largest sender of students to the U.S., and the largest African sender by a significant margin. In recent years, Nigerian enrollments in the U.S. have begun to catch up with the U.K.: Whereas a few years ago, the ratio of Nigerian students in the two countries was 2:1, it is now 1.5:1.

- Malaysia: According to UIS, 4,943 Nigerians enrolled in Malaysian institutions in 2015, making the country the fourth most popular destination among Nigerian students. The country has actively sought to position itself as an international education hub, publishing a 10-year plan to attract some 250,000 international students (up from 108,000 in 2015) by 2025.

- Ukraine: Four years ago, Ukraine did not make the top five among Nigerian destinations, but now there are 3,300 Nigerian students there. The very low cost of Ukrainian higher education and living expenses, coupled with a limited number of bilateral scholarships as incentive, makes Ukraine an attractive destination. It is reported that medicine, aviation, economics and engineering are the most popular fields of study for Nigerians in Ukraine.

- Canada: While UNESCO reports 3,257 Nigerians studying in Canada, the Canadian Bureau for International Education reported 8,620 in 2014, and the Canadian High Commissioner to Nigeria reported 9,000 in 2015. Canada stands to benefit from visa restrictions discouraging Nigerians traveling to the U.K. or the U.S., and has extended its welcome mat with the theme, “Our Diversity is Our Strength.”

A handful of other destinations seem to be gaining traction as well, due in part to cutbacks in Nigerian government scholarships.[6]EducationUSA advisors report that families are increasingly cost-conscious in their choice of study destinations. Nigeria’s government reports that more students are enrolling in institutions in countries that are party to the Federal Ministry of Education’s Bilateral Education Agreement Scholarship Awards. These include Russia, Morocco, Algeria, Serbia, Hungary, Egypt, Turkey, Cuba, Romania, Ukraine, Japan, Macedonia, China, Mexico, and South Korea.[7]BEA accounts are supported by anecdotal evidence as well. It’s a reasonable assumption that generally increasing numbers of Nigerians in these countries are sparked by the availability of these BEA Awards.

Nigerians Students in the United States: Who Are They, Where Do They Go, and What Can We expect in the Future?

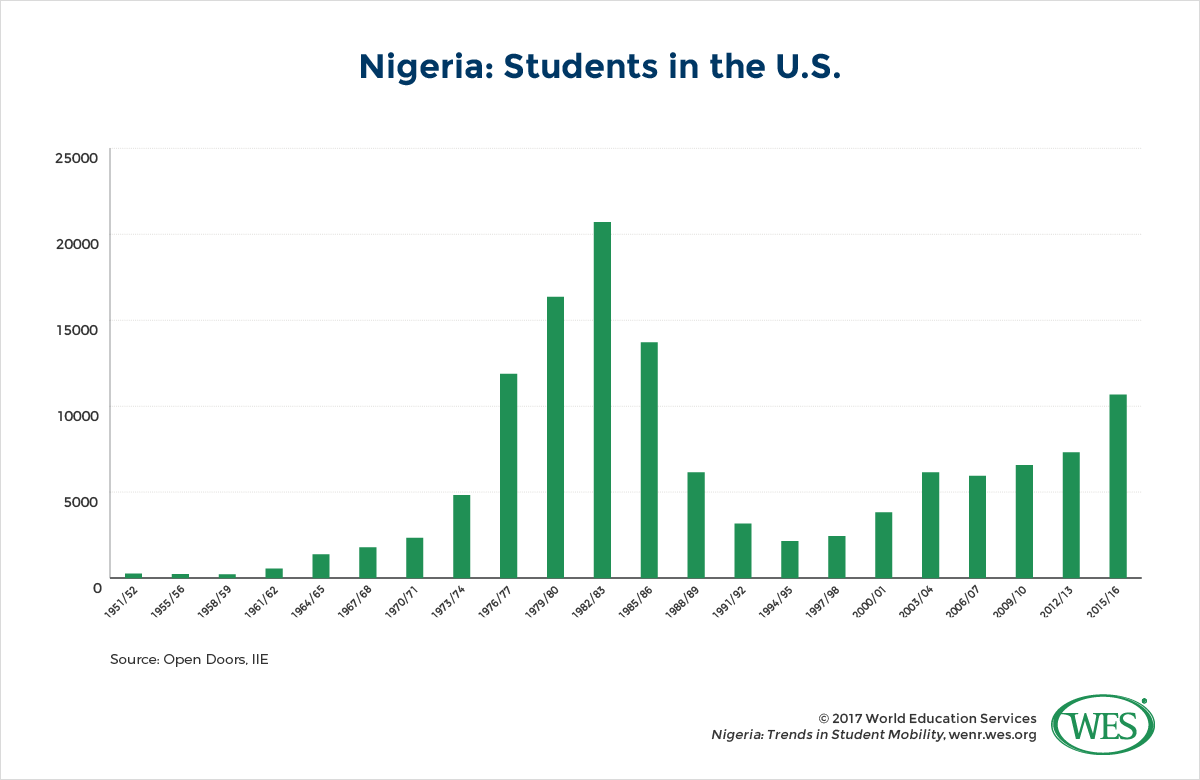

According to the Migration Policy Institute, Nigerians comprise the largest group of African immigrants to the U.S. They are highly educated – 37 percent of first and second-generation immigrants in the U.S. hold undergraduate degrees (as compared to 20 percent of the overall U.S. population.)[8]The Nigerian Diaspora in the United States,” 2015 The Migration Policy Institute (www.migrationpolicy.org), accessed February 14, 2017. Nigerians also have a well-established track record on U.S. campuses. The first surge of Nigerian students in the U.S. began about 40 years ago. It peaked in 1982/83, with more than 20,000 higher education enrollments, and fell by almost 90 percent in the mid-1990s. In many ways, that first surge laid the groundwork for a second wave of Nigerian students which has seen a steady increase in enrollments over the past decade. The trend lines for the two waves are vastly different, due in large part to the source of funding: Current growth is fueled by individual and societal aspirations; earlier growth was fueled by government investment in a young country.

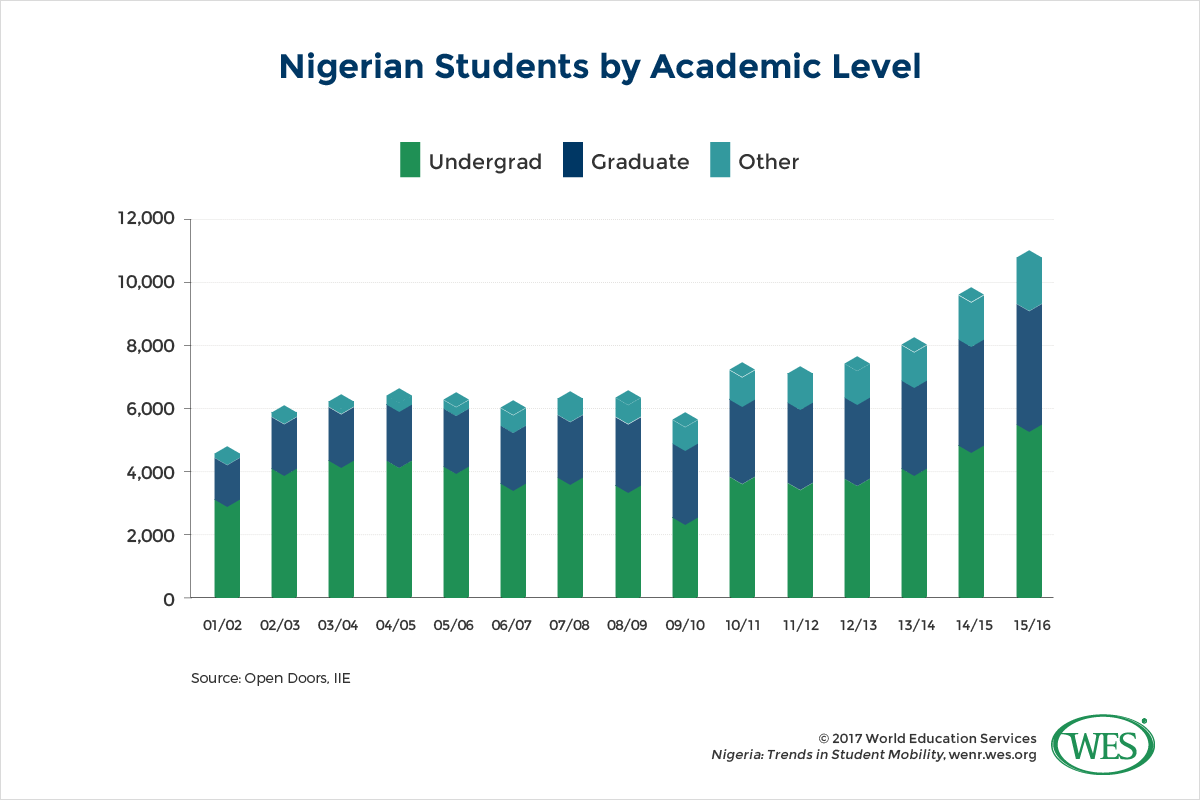

Just over half (51 percent) of Nigerian students enrolled in the U.S., or 5,400, are undergraduates. Some 3,800 – or 36 percent – are graduate students. Eleven percent participate in optional practical training (OPT), a relatively high number that shows the importance of practical experience to Nigerians. Very few Nigerians – 2 percent – are enrolled in non-degree programs, and English language study is virtually nonexistent because the official language and sole language of instruction is English.[9]Another census, compiled by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, is regularly updated in Mapping SEVIS By the Numbers. In its edition of November 7, 2016, SEVP reports 14,495 Nigerian students with active F and M visa status in their system. Presumably, if J visa holders were included, the number and percent of graduate students would be higher. Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) and Open Doors figures do not match because they count different categories of students on different dates: Open Doors includes students in F, M and J status who are enrolled in accredited tertiary institutions, and includes non-degree and OPT students for the previous academic year, as reported by the institutions. The SEVIS report includes students and dependents in F and M status enrolled at any institution authorized to issue I-20s, as of a specific date, as recorded in the SEVIS system.

In the U.S., Nigerian students are enrolled in nearly 1,000 institutions in all fifty states plus the District of Columbia. The top five destination states are Texas, New York, Maryland, Florida and Massachusetts, while other popular urban areas include Chicago, Baltimore, and Washington DC. Nigerians think big: 61 percent are enrolled, at all levels, in doctoral-granting institutions. Nine out of the top fifteen universities enrolling Nigerian graduate students are Research 1 institutions. Eighteen percent head for Texas, which became home to large Nigerian communities during the oil boom of the 1970s and 1980s.

Nearly seventy percent of Nigeria’s students enroll in public colleges and universities. The community college market is small, but growing as Nigerians seek the most cost-effective education. Some 17 percent of Nigerian undergraduates are enrolled in community colleges. Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and Christian colleges are also popular.

It’s unclear how the current political environment in the U.S. may affect Nigerian enrollments. Used to navigating uncertain political waters, Nigerian students may well be resilient to rhetorical bluster although, if enacted, broadly restrictive new visa policies could hinder their entry. For now, the recruitment market is ripe, and international educators who recognize Nigeria’s potential will be rewarded.

EducationUSA and the U.S. Commercial Service are partnering to hold Nigeria’s 17th annual College Fair in Lagos and Abuja (continuing to Ghana ) in late September, offering an ideal opportunity to visit the country with full U.S. government support.

References

| ↑1 | Based on a comparison of UNESCO Institute for Statistics data captured in 2012 and again in late 2016. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. |

| ↑3 | As of March 2017, UIS reports 3,257 Nigerian students in Canada. The discrepancy is likely due mostly (though not entirely) to the type of student mobility data captured. UNESCO UIS only captures degree mobility, i.e., students who have gone to a country to pursue an actual degree. Other agencies may capture credit mobility, i.e., students who study abroad for a semester, year, or summer and return home and apply the credits earned in that country to a degree in their home country institution. Still others, such as the Chinese Ministry of Education, also report inbound international vocational students toward their international student estimates. |

| ↑4 | The African Development Bank’ defines middle class as people spending between $2 and $20 per day. By this definition, middle class Nigerians would have disposable income, but not necessarily sufficient resources to pay for university outside the country. According to the New York Times, “Standard Bank, a South African bank with branches across the continent, estimated that Nigeria’s middle class grew by 600 percent from 2000 to 2014. While 4.1 million Nigerian households are now considered middle class, or 11 percent of the total population, an additional 7.6 million households would make it into that category by 2030, according to the bank’s projections.” (From “Nigeria Goes to the Mall,” The New York Times, Norimitsu Onishi, January 5, 2016) |

| ↑5 | It should be noted that the availability of government-funded scholarships is subject to change. |

| ↑6 | EducationUSA advisors report that families are increasingly cost-conscious in their choice of study destinations. |

| ↑7 | BEA accounts are supported by anecdotal evidence as well. It’s a reasonable assumption that generally increasing numbers of Nigerians in these countries are sparked by the availability of these BEA Awards. |

| ↑8 | The Nigerian Diaspora in the United States,” 2015 The Migration Policy Institute (www.migrationpolicy.org), accessed February 14, 2017. |

| ↑9 | Another census, compiled by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, is regularly updated in Mapping SEVIS By the Numbers. In its edition of November 7, 2016, SEVP reports 14,495 Nigerian students with active F and M visa status in their system. Presumably, if J visa holders were included, the number and percent of graduate students would be higher. Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) and Open Doors figures do not match because they count different categories of students on different dates: Open Doors includes students in F, M and J status who are enrolled in accredited tertiary institutions, and includes non-degree and OPT students for the previous academic year, as reported by the institutions. The SEVIS report includes students and dependents in F and M status enrolled at any institution authorized to issue I-20s, as of a specific date, as recorded in the SEVIS system. |