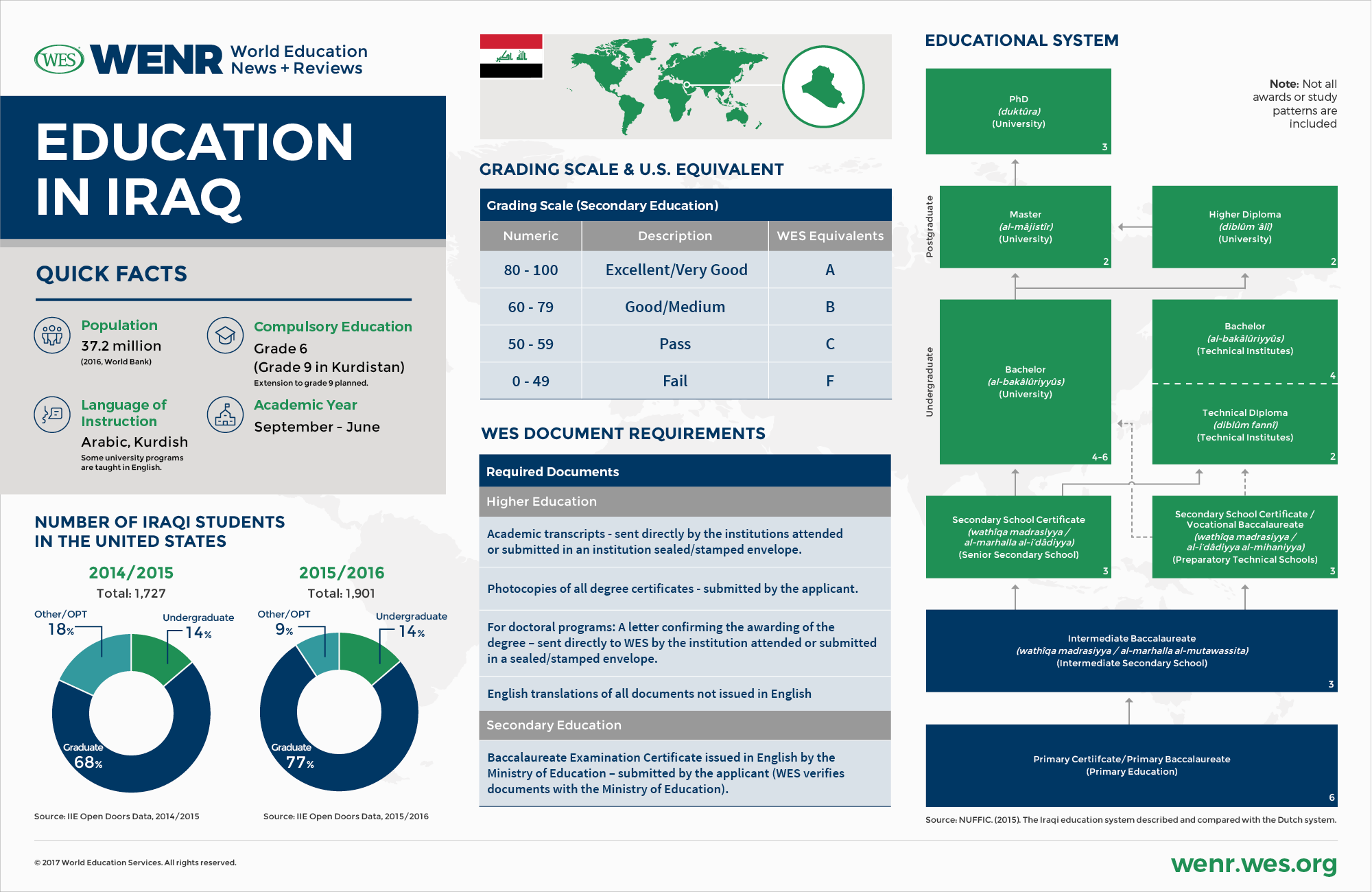

Education in Iraq

Sulaf Al-Shaikhly, Advanced Education Specialist, and Jean Cui, Research Associate, WES

This education profile describes Iraq’s education system, and trends in inbound and outbound international student mobility. It includes sample educational documents, and discusses credential evaluation challenges specific to the Iraqi system.

Introduction

Iraq is a fast-growing multi-ethnic country of 37.2 million people (2016, World Bank) neighbored by Jordan, Syria, Turkey, Iran, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. The country is home to a variety of ethnic groups, including Arabs (75 to 80 percent of the population), Kurds (15 to 20 percent), Turkmen, Assyrians, Shabak, and Yazidi (5 percent combined). The most dominant religions are Islam (Sh’ia Islam followed by 55 to 60 percent of the population and Sunni Islam (40 percent).[1]According to the CIA World Factbook (2017). Estimates on the percentages of religious groups vary, depending on the source. Minority religions include: Christianity, Yazidism, Sabean Mandaeanism, Baha’i faith, Zoroastrianism and others (less than 1 percent combined). The different languages and dialects spoken in the country include the official languages of Arabic and Kurdish, as well a Turkmen, Syriac (Neo-Aramaic), and Armenian, which are considered official languages only in areas populated by these minorities, predominantly located in the north of the country. (CIA World Factbook) Arabic is spoken or understood by the vast majority of Iraqis.

Few countries in the world have been more severely affected by war over the past decades than Iraq. Iraq’s education system, like the country as a whole, remains crippled by the dislocation of people and the destruction of critical infrastructure due to years of crippling economic sanctions and a series of devastating wars, from the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s to the first Gulf War in 1991, and the 2003 U.S-led invasion of Iraq that was followed by civil war, which continues to affect the country until today. The greatest destruction of infrastructure and academic institutions happened in 2003 and after. UN scholars have estimated that “some 84 percent of Iraq’s institutions of higher education … [had] been burnt, looted, or destroyed” by 2005. Many universities today continue to be impacted by electricity outages and a lack of equipment and resources. According to UNICEF, infrastructural damage has also resulted in 50 percent of public schools in central Iraq failing national construction standards or being inadequately maintained, with 1.2 million children (13.5 percent of school-aged children in Iraq) excluded from participation in basic education as of 2013. Drop-out and repetition rates in schooling remain high, particularly among poorer segments of society.

In addition to infrastructure destruction, education in Iraq has been deeply affected by large numbers of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs), especially in areas with ongoing fighting. Since the U.S.-led attack in 2003, a minimum of 400,000 to 650,000 civilians and combatants have been killed as a result of the war, and more than 3 million people have been displaced. Almost half of the children among the current IDP population remain out of school. Warfare has caused the interruption of studies at higher education institutions and affected teachers and faculty, many of whom are deliberately targeted in the country’s sectarian conflict between Shiites and Sunnis. The flight of professors and other members of the country’s intellectual elite has resulted in a massive brain drain and the deterioration of educational quality. Universities are chronically understaffed and senior lecturers are being replaced with poorly trained junior faculty. At least 324 professors have been assassinated between 2005 and 2013 – likely a low-ball estimate, given a high number of undocumented cases. While there are no reliable statistics on how many teachers have fled the country, the Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education estimated that more than 3,250 professors left between February and August of 2006 alone. Thousands more have since fled, along with large numbers of medical doctors and other professionals.

The decay of education in Iraq is particularly tragic, since Iraq used to have one of the most developed education systems in the Middle East. Despite the reign of terror it unleashed on the population under President Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s socialist Baath party in the 1970s and 1980s succeeded in achieving progress against a number socioeconomic indicators, including access to education. The government came close to eradicating illiteracy in the 1980s and achieved some of the best enrollment ratios, dropout, and repetition rates in the Middle East and North Africa with government spending on education increasing to 6 percent of GDP in 1984, funded by the country’s growing oil revenues. War, international sanctions, and economic crises have since then reversed many of these advances. Illiteracy among 15 to 24 year-old Iraqis stood at more than 18 percent in 2015, and Iraq’s government expenditures on education are presently among the lowest in the Middle East, accounting for only 5.7 percent of total government expenditures in 2016, compared to 18.6 percent in neighboring Iran (2015) and 14.1 percent worldwide (2013).

Given these circumstances, Iraq has in recent years nevertheless made considerable progress in improving access to education. Elementary school enrollments, for example, have recently been growing at a rate of 4.1 percent annually, while enrollment ratios in lower secondary school in 2013 were 30 percent higher than in 2000. Legacies of war, the prevalence of political violence, population growth and precarious funding levels for education, however, make it likely that the country will continue to face considerable challenges in improving education for the foreseeable future.

A Fragile Federation

Like other former colonies, Iraq is less of a nation-state than a “construct” with arbitrary boundaries drawn by the British colonial rulers – a fact that resulted in diverse ethnoreligious groups being incorporated in the same country. Since the country’s independence in 1932, Iraq has been characterized by conflict between the politically dominant Sunni Arab minority in the center of the country, Shiite Arabs, which are predominantly located in the South, and the Kurds in the North. Even though the Kurdistan region had de jure autonomy under Saddam Hussein, the Kurds remained brutally repressed and did not achieve de facto autonomy until the U.S. intervened and established a military no-fly zone in the north of the country in the 1990s. After the ouster of the Sunni-controlled Baath regime, Iraq in 2005 adopted a new constitution that established the country as a federation of 18 governorates, three of which form the autonomous Kurdistan region. Despite having achieved autonomy status, many Kurds continue to dream of an independent Kurdish state. In September 2017, the Kurdistan region held a referendum in which 92 percent of the population voted in favor of separation from Iraq – a development that could ignite yet another war in the region, as an independent Kurdish state is fiercely opposed by the governments of Iraq, Turkey, and Iran.

Outbound Student Mobility

Political instability, war, deteriorating living conditions, and a lack of high-quality study options in Iraq have been the key drivers of Iraqi student mobility over the past decades. The fact that Iraq is a middle-income country with a per capita GDP of only US$ 4,610 (2016, World Bank), however, means that the financial means of many Iraqis are limited and that outbound student mobility is strongly dependent on scholarships and sponsorships provided by the government, NGOs, foreign governments and international organizations. Most of these scholarships and funding programs are designed to meet urgent needs in public service and infrastructure reconstruction and are available in STEM fields, agriculture, public health/medical sciences, and English language.

Some of these scholarship programs are quite extensive. Programs run by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research and the Higher Committee for Education Development in Iraq (HCED), for example, cover tuition and travel expenses for thousands of Iraqi students. The Human Capacity Development Program in Higher Education (HCDP) funded by the Kurdistan Regional government provides US $100 million annually for graduate students from the Kurdistan region to study in universities in North America, Europe, Australia, Asia, and neighboring countries. In the U.S., Fulbright scholarships have been made available for qualified Iraqi students, most recently for study in U.S. master’s degree programs in all majors except for medicine and other clinical studies.

The source of funding plays a key role in determining the study destinations of Iraqi students. Self-funded students tend to go to neighboring countries such as Jordan and Turkey, or countries like Malaysia and India, where tuition and costs of living are lower than in high-cost countries like the United States. Scholarship-funded students, by contrast, are often encouraged to study in accredited institutions in English-speaking countries, such as the U.S. and the United Kingdom. To minimize brain drain, students on Iraqi government scholarships may also have to agree to repay their scholarships unless they return to Iraq to work after completing their studies.

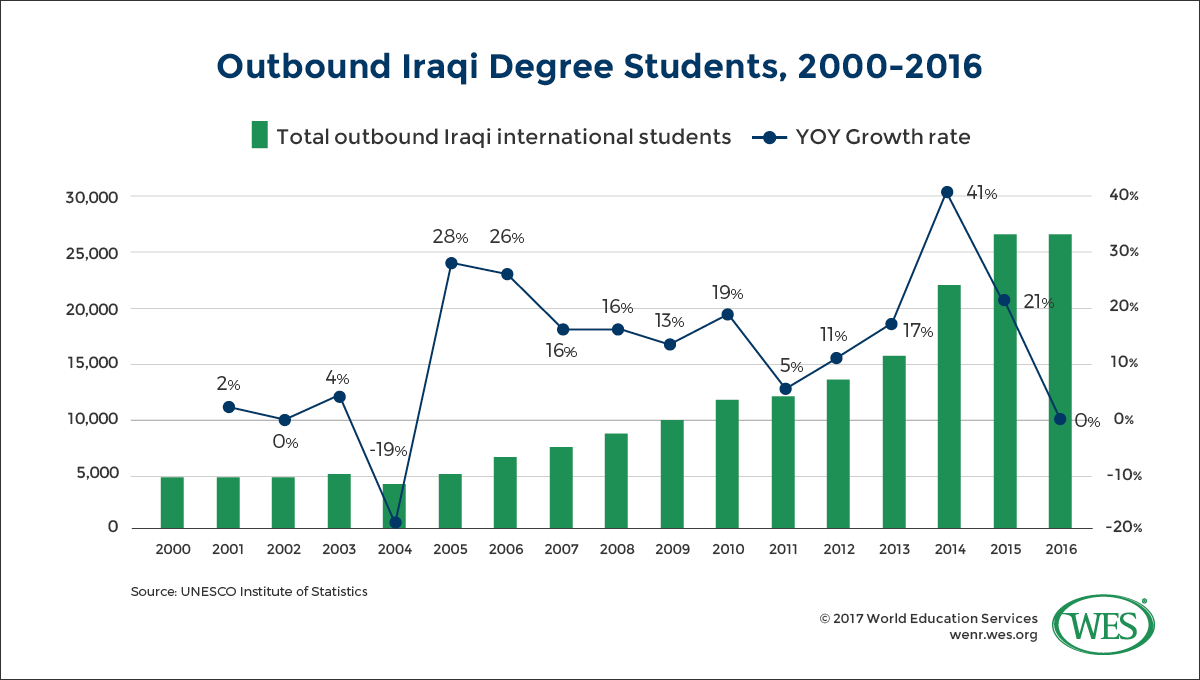

Student mobility from Iraq has been growing strongly in recent years, increasing by 428 percent between 2005 and 2016, from 5,493 to 28,993 degree students (UNESCO).[2]Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers that may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. This steep increase follows a period of stagnation in the early 2000s and a sharp drop in outbound mobility during the Iraq war, which caused outbound student numbers to plunge by 18.6 percent between 2003 and 2004. The current top destinations of Iraqi students include Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, Ukraine, and Malaysia. The U.S. is presently the 7th most popular destination country of Iraqi students.

Iraqi Students in the U.S.

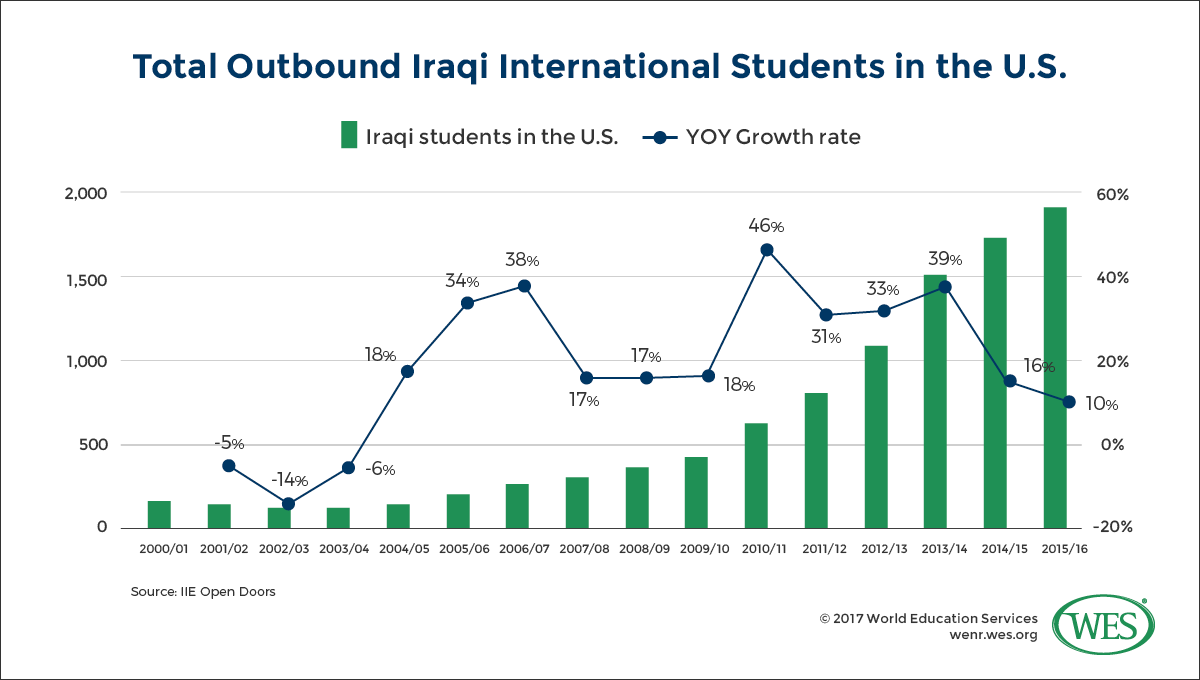

Iraqi students have been coming to the U.S. for higher education for more than 70 years, but the inflow of students was inhibited by war, political hostilities and economic sanctions since the 1990s. Since the ouster of Saddam Hussein and the U.S. occupation of Iraq, however, this situation has improved. In 2008, Iraq and the U.S. agreed on a Strategic Framework Agreement that included goals to increase cultural exchanges and cooperation in higher education and research. The number of Iraqi students coming to study in the U.S. has since then increased by 429 percent, from 359 students in 2008/09 to 1,901 students in the 2015/16 academic year (IIE, Open Doors). The majority of these students (nearly 77 percent) study at the graduate level, 14 percent at the undergraduate level, and 9 percent in non-degree and OPT programs. According to the Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education, the vast majority of Iraqi graduate students in the U.S. (nearly 79 percent) are enrolled in Ph.D. programs, reflecting the country’s high demand for skilled academics in the scientific research sector.

Many Iraqi students in the U.S. have limited English language abilities and are, therefore, often required by universities to complete a semester or two in language training before they are eligible to enroll in degree programs. However, students with government scholarships are often sponsored to attend intensive English language courses for as long as a year before they start their degree programs. In addition, the U.S. is reportedly financially supporting the establishment of ESL training programs in Baghdad to improve students’ English language skills and prepare them for international education.

Compared to big sending countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, or Kuwait, Iraq remains a secondary market for U.S. universities in the Middle East region. One area that could offer short-term opportunities for growth and student recruitment are faculty training programs sponsored by Iraqi universities, the government, and international organizations to ease Iraq’s acute shortage of researchers and instructors caused by the mass exodus of academics fleeing political violence.

Future Potential for Outbound Mobility

Iraq is home to one of the fastest-growing and most youthful societies in the world. More than 40 percent of the country’s people are below the age of 14 and the population is currently growing at an annual rate of 11 percent. Based on current growth rates, the UN expects the country’s population to surge to 50 million by 2030. Swelling college-aged youth cohorts will greatly increase demand for education and pose further challenges to the fragmented, conflict-ridden Iraqi state, which is already ill-equipped to handle current demand. Since Iraq’s government income is largely dependent on oil revenues, a perpetuation of low prices for crude oil would continue to undermine the financial foundations of the Iraqi government and leave the country dependent on foreign aid, even if political stability can be achieved and sustained. Observers have noted that unless long-term policy solutions will be implemented soon, population growth will diminish public resources and lead to catastrophic increases in unemployment and poverty.

In terms of outbound student mobility, however, burgeoning demand for education means that Iraq is a growth market with considerable potential, even though the provision of scholarships will be crucial to steer the rising demand for higher education towards high cost countries like the United States. In light of the obstacles Iraqi students currently face in studying abroad, distance education may offer a promising alternative to educate greater numbers of Iraqis. The Iraqi government, UNESCO and foreign universities have already launched initiatives to expand e-learning and distance education at both the secondary and tertiary level.

Inbound Student Mobility

Unsurprisingly, inbound student mobility to Iraq is minimal, due to a lack of quality education, limited resources and continued conflict, prominently featured in the news due to the war against the “Islamic State” (ISIS) in the northern parts of the country. The same factors that drive outbound mobility constitute obstacles for inbound mobility and make the country currently an unattractive study destination even for neighboring countries. UNESCO does not report recent inbound student numbers for Iraq, but between 2000 and 2004, the number of foreign degree students in the country dropped from 8,280 to 3,557 (UIS). IIE only reported six U.S. students pursuing studies in Iraq in 2013/14 and zero students since then.

Administration of the Education System: Baghdad and Erbil

The federal Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research in Baghdad are the administrative bodies responsible for overseeing education in all Iraqi governorates except for Kurdistan. The roles of the two ministries include funding, policy and planning, quality assurance, staff appointments, the setting of admission requirements, administration of national examinations, and the development of curricula and learning materials.

The Kurdistan Region: Separate Administrative Oversight

The Kurdistan Region includes the provinces of Sulaymania (Sulaymani in Kurdish), Erbil (Hawler in Kurdish), and Duhok. The autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is headquartered in the administrative center of Erbil. Education is administered by the Kurdish Ministry of Education, and the Kurdish Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research.

The basic structure of the education system in Kurdistan is similar to that in the rest of Iraq, except that compulsory education lasts until grade 9 (basic education) as opposed to grade 6 in the remainder of the country. The range and content of subjects studied in elementary and secondary education is also slightly different, since Kurdish language is an additional subject and the language of instruction is mostly Kurdish.

There are currently 15 public universities and as many as 15 private universities in operation in Kurdistan. Many of the public universities in Kurdistan already existed prior to the establishment of the autonomous Kurdistan Region and used to be overseen by the central government in Baghdad, but the withdrawal of the central government from the Kurdish region in the 1990s meant that these institutions were factually administered locally. Today, the KRG has established its own formal mechanisms for quality assurance and recognition of higher education institutions. After long periods of isolation and a lack of resources, recent reforms and relative stability compared to other parts of Iraq have until recently helped to improve education in Kurdistan, even though funding levels remain insufficient.

In addition to regional recogniton, several public universities in Kurdistan are also recognized by the central government in Baghdad, even though the Federal Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research since 2011/12 does no longer list these institutions on its website. One possible reason for this could be that students from outside of Kurdistan can no longer apply directly for admission to Kurdish universities (they can only transfer from other universities in Iraq).

Private universities in Kurdistan are, for the most part, not recognized by Iraq’s federal government, even if they are recognized by the autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government. The American University of Iraq (Sulaymani) and Cihan University were the first two private universities in Kurdistan to receive federal accreditation in 2017.

At least two universities, The American University of Iraq (Sulaymani) and University of Kurdistan – Hawler teach curricula entirely taught in English. English is also the language of instruction in science courses at other universities in the Kurdish region.

The fact that the political situation in Kurdistan was until recently relatively stable compared to other parts of Iraq has turned the region into a safe haven for internally displaced persons. Enrollments at all levels of education in Kurdistan have increased in recent years, driven by the influx of refugees, most notably from combat areas in the war against ISIS. Given the limited infrastructure in the Kurdish region, this inflow has further strained the already limited capacity of the education system.

Access to public university education is becoming increasingly difficult and competitive, despite growing numbers of new private providers seeking to absorb excess demand. According to the Kurdish Director of Central Admissions, in 2011, for instance, 5,000 students were excluded from entering public higher education, as only 29,000 students out of 34,000 that applied for admission ended up getting admitted.

In Brief: Iraq’s Education System

Elementary Education

Public education in Iraq is free at all levels. The Ministry of Education provides all teaching materials in elementary and secondary education, oversees teacher training, and develops curricula for each stage of schooling. Education is compulsory until age 12 (grade 6), except in Kurdistan, where pupils are required to stay in school until grade 9.

The elementary education cycle in Iraq is 6 years long, from grade 1 to grade 6. Students are registered in the 1st grade at the age of 6, following a non-compulsory 2-year pre-school stage (ages 4 and 5).[3]Ministry of Education www.moedu.gov.iq

Graduation from elementary school requires passing a national exam administered by the Ministry of Education at the end of the 6th grade. Pupils are awarded an Elementary Certificate (Al-Shahada Al-Ibtedaya), also referred to as Elementary Baccalaureate Certificate (Sharadet Al-Bakaloria Al-Ibtedaya).

Since 2003, there have been several changes in the elementary education sector. Curricula and subjects taught have been revised. For example, English language is now being introduced in the first grade instead of in the fifth grade.

In addition, prior to 2003, there were no private elementary schools, whereas currently there are as many as 1,200 private schools (2012) operating with licenses from the Ministry of Education. These schools have to comply with ministry regulations and offer the same curricula as public schools, but often teach additional classes, such as further foreign languages. Private schools are often of high quality, compared to the underfunded public schools, but they usually charge extremely high fees, only affordable for wealthy elites.

The school year consists of two semesters of 16 weeks each, and the Ministry of Education stipulates a minimum number of 30 hours per week. Students attend school for 6 days a week, from Saturday through Thursday, with an average study load of 5 hours a day. Classes are usually 45 minutes in length.[4]Ministry of Education www.moedu.gov.iq

Subjects studied in the sixth grade include Arabic, English, Mathematics, Science, History, Geography, Islamic Studies, and National Education.[5]Ministry of Education, General Directorate of Curricula www.manahj.edu.iq In the Kurdistan Region, Kurdish language is part of the curriculum (or other minority languages, where applicable).

Students are expected to do homework assignments each day, and usually need to pass written and oral exams (depending on the grade) throughout the semester, in addition to a final examination at the end of the year.

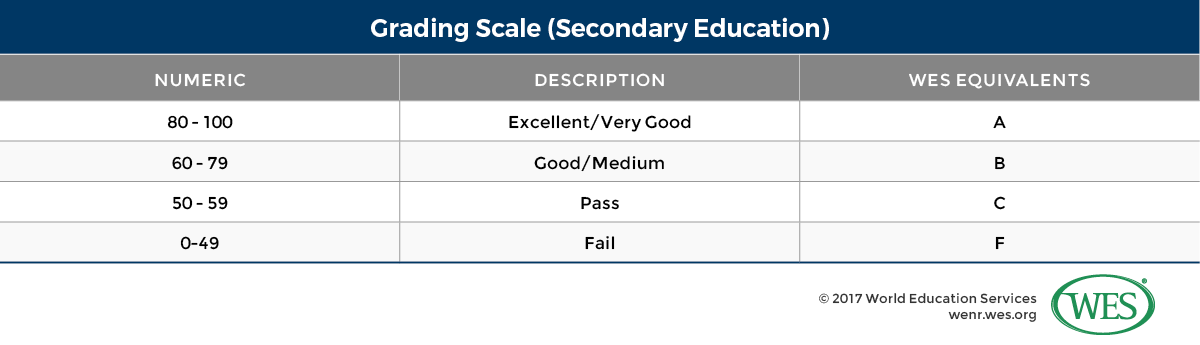

The grading scales used in elementary education are:

- First 4 years (1st grade- 4th grade): 0 – 10 (5 or higher is a passing grade)

- Last 2 years (5th grade- 6th grade): 0 – 100 (50 or higher is a passing grade)[6]NUFFIC. (2015). The Iraqi education system described and compared with the Dutch system.

Secondary Education

Entry into secondary education requires the Elementary Certificate. The secondary cycle is 6 years in length (ages 12 to 18) and is divided into two three-year phases: the intermediate phase (ages 12-15) and the preparatory phase (ages 15-18). Each phase ends with a national examination administered by the Ministry of Education. After passing the national examination at the end of the third intermediate year, students receive an Intermediate Certificate (Al-Shahada Al-Mutawasita), also called Intermediate Baccalaureate (Shahadet Al-Bakaloria Al-Mutawasita).

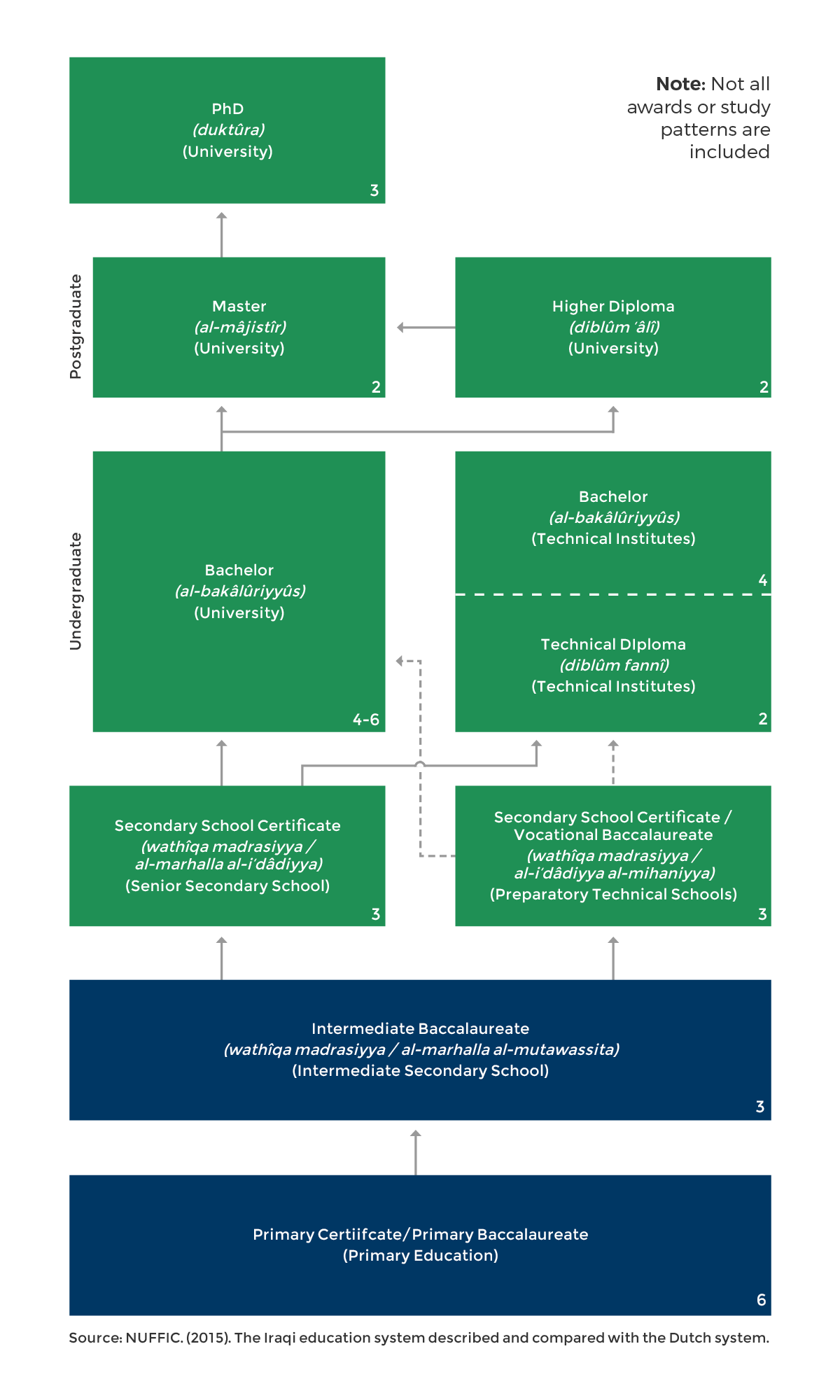

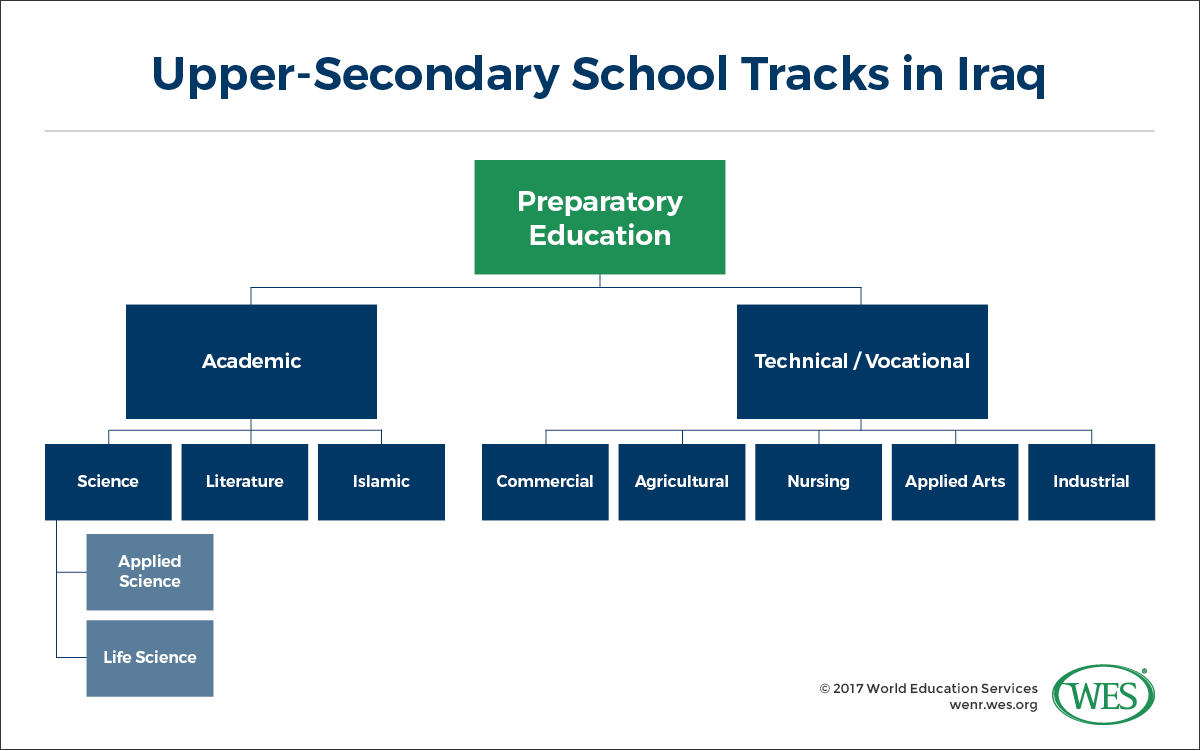

Subsequently, students have the option to choose between different types of upper-secondary preparatory school tracks as shown below. Academic streams prepare students for tertiary education, whereas technical-vocational programs have a strong emphasis on practical training, and are designed to directly prepare graduates for entry into the labor market, even though higher education pathways also exist for graduates in these streams.

Upper-Secondary School Tracks in Iraq

In 2015, the Ministry of Education split the science stream into two separate streams: Applied Science and Life Science. This was done to provide students with more options and funnel them into different educational pathways. Graduates of the different streams are usually steered towards the following paths:

- Applied Science graduates can pursue higher education at colleges of engineering, universities of technology, technical universities, institutes of administration, and colleges of science, agriculture, education, and economics and administration.

- Life Science graduates can pursue higher education at colleges of medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, nursing, and veterinary medicine, medical institutes and colleges of science (biology, chemistry, biotechnology), agriculture, and education (biology, chemistry).

- Literature graduates: Literary majors at universities and institutes.

- Islamic Studies graduates: Literary majors at colleges of education and college of arts.

- Technical/Vocational graduates are mostly limited to pursue higher education at post-secondary technical institutes and colleges under the purview of Foundation of Technical Education. The top ten percent of students scoring highest in the final national examination are eligible to enroll at universities in a suitable major.

Subjects studied in the last year of the preparatory stage include, for example, Arabic, English, Islamic Studies, Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, and Biology in the science stream; Arabic, English, Islamic Studies, History, Geography, and Economics in the literature stream. Kurdish language is included in the curriculum in the Kurdistan region.[7]Ministry of Education www.moedu.gov.iq

Throughout the program, students usually need to pass written and oral exams in addition to a final exam at the end of each year. Recent reforms, however, have introduced a semester-based system allowing students to study subjects in discrete semesters rather than annual two-semester blocks.[8]Ministry of Education www.moedu.gov.iq

At the end of the last year of preparatory education (grade 12) all students sit for a national examination. Upon passing of the exam, they are awarded the Preparatory Certificate (Al-Shahada Al-Idadya), also known as Preparatory Baccalaureate Certificate (Shahadet Al-Bakaloria Al-Idadya).

The final baccalaureate examination score is what determines students’ eligibility for admission to higher education institutions. Admission is highly competitive and even the smallest deviations in score can make the difference between being admitted into first- or second-choice programs.

Elementary School Teacher Programs

Aside from attending preparatory school, students could, until recently, enroll in teacher training programs after completing intermediate education. Five-year programs at Teachers’ Institutes led to a post-secondary diploma credential that allowed graduates to work as elementary teachers.[9]Ministry of Education www.moedu.gov.iq (Programs were alternatively offered as 12+2 post-secondary programs.) Since 2012, however, intake into these programs has been suspended in order to allow absorption of graduates from previous years into the job market, before the government will phase out the programs altogether, eventually requiring all teachers to hold a bachelor’s degree in education.

Private Secondary Schools

Until 2003, there were no private secondary schools in Iraq. Since then, a sizeable and growing number of private schools have been established, now enrolling close to 3.5 percent of Iraq’s upper-secondary students (38,100 out of a total of about 1.1 million upper-secondary students in 2015/16). Even though these expensive schools may offer additional classes, students study the national curriculum and have to sit for the national exams at the end of the intermediate and preparatory stages.

A number of international high schools have also started to operate in Iraq, mostly in the Kurdistan region. Unlike private Iraqi schools, these institutions offer curricula from various systems of education like the U.S., U.K., France, Germany, and Turkey, as well as International Baccalaureate programs. The Kurdish Ministry of Education in 2017 listed 97 private schools on its website. One example of such a school is the American International School – Kurdistan.

Higher Education

The standard admission requirement for entry into tertiary education in Iraq is the Preparatory Certificate, respectively the Baccalaureate examination. Students usually apply through a centralized application process by submitting an online application to the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, indicating their school preferences. The Central Office of Admission of the Ministry then places students in higher education institutions based on their Baccalaureate examination scores and admission quotas at universities. In Kurdistan, the process is similar to a central university admissions office matching students with available seats in study programs.

Programs at free public higher education institutions institutes are usually more in demand in Iraq than those offered by private institutions. There a no entrance examinations, but admission to public institutions is very competitive and only students with high baccalaureate scores are accepted. Those with lower scores are usually accepted at private universities in the same majors.

As of 2017, there are 35 public universities and 55 private universities and colleges in Iraq (outside of Kurdistan). Of the 15 public and 15 private universities in the Kurdistan region, nine public and two private universities are recognized by both the Kurdish Ministry of Higher Education and the Federal Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research in Baghdad. The other private institutions in Kurdistan are only recognized by the Kurdish Ministry of Higher Education. [10]Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research http://mohesr.gov.iq/

Accreditation in Iraq is institution-based – there is no accreditation process for individual study programs. The final license for institutions to operate is granted by the Iraqi Council of Ministers, a high-level government body, following a review process by the Ministry of Higher Education. The licensing of private institutions is overseen by a Private Higher Education Council, but final approval to operate is also granted by the Council of Ministers. The assessment criteria for the approval of institutions include adequate funding structures and teaching staff. Institutions must also be situated in Iraq, have no foreign affiliations, and make notable contributions to higher education and scientific research. Bachelor’s programs offered by the institution must be four years in length, and the institution must have been in existence for at least five years.[11]See: Law of the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of 1988 (amended).

Concrete and reliable numbers on student enrollments are difficult to obtain, but according to the U.S. Department of State, higher education institutions in 2016 enrolled “a total of 490,000 students (95 percent are undergraduate and 55 percent are male)”. This compares to an estimated 424,900 students in 2005, the last year for which the UNESCO Institute of Statistics provides data on tertiary enrollments in Iraq. According to the Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education, a total of 121,285 students were admitted to higher education programs in 2016/17 in Iraq (in addition to 30,039 in the Kurdistan region). As per UNDP, the number of new students admitted to higher education annually in Iraq grew by 41,252 students between 2003 and 2011. Such increases in enrollments stand in contrast to decreased education spending, which dropped considerably in recent years, from 7.9 trillion Iraqi dinars in 2013/14 to 6.7 trillion Iraqi dinars in 2015/16.

Undergraduate Education

The standard first cycle tertiary degree in Iraq is the bachelor’s degree. Programs in humanities and the sciences are typically four years in length and commonly lead to the award of a Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science degree.

Programs in professional disciplines studied at universities are either six years (medicine) or five years in length (for example pharmacy, dentistry, veterinary medicine, and architectural engineering).

Study is usually on a full-time basis in a traditional classroom setting, even though some programs may be offered in a full-time evening study mode to accommodate students holding employment. Unlike in regular programs, students enrolled in evening programs may be charged tuition fees.

The curricula are specialized and include only a few general education courses; they are standardized and allow little room for elective subjects and customization. Courses are quantified in credit units and most four-year programs usually require between 120 and 140 credits for completion. Students have to pass a set number of courses each year in order to be promoted to the next year, otherwise they will have to repeat the entire year. There are both semester-based and final annual examinations in June of each year. Students can resit the final annual examination one time in September if they fail on the first attempt. In order to graduate, students need to pass all courses in the final year and complete a graduation or research project. Students may also be required to complete summer training programs (interships).

Some notable changes since 2003 include:

- Al-Nahrain University (formerly known as Saddam University) used to offer a combined bachelor’s and master’s program of 5-year duration, including a 3-year bachelor’s and 2-year master’s component. This program has been terminated in 2005 and the university now offers the same standard bachelor’s and master’s degree programs offered at other universities in Iraq.

- Some new universities in Kurdistan introduced study programs modeled after Western education systems. The University of Kurdistan Hawler, for instance, used to offer a European-style three-year bachelor’s degree. Since 2014, however, these changes have been reversed and all Kurdish universities now again offer four-year degrees.

Graduate Education

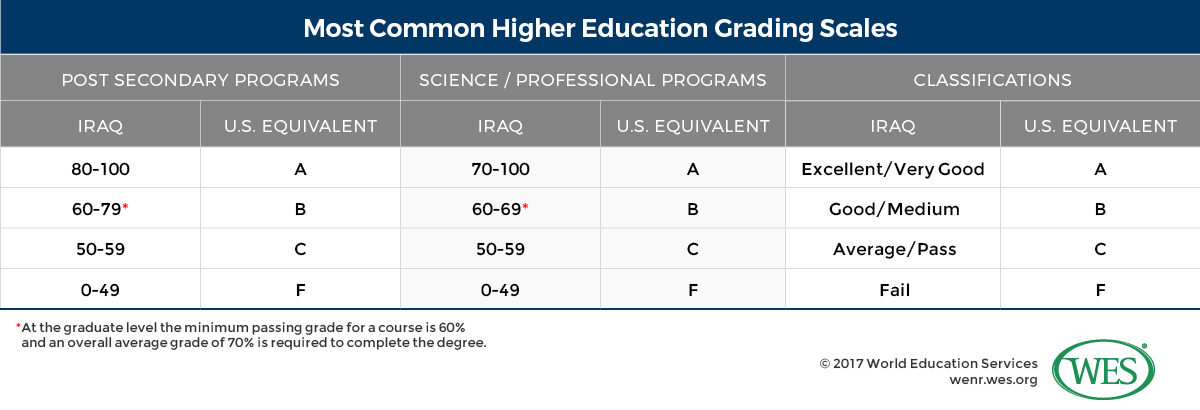

Graduate programs are usually taught at universities or higher institutes. Master’s-level education is reserved for only the best students (that is typically those that score above 65 percent in their bachelor’s program), and each university department determines their own admissions quotas. Students apply directly to the individual departments/colleges, and usually have to pass entrance examinations. They must also have a bachelor’s degree in a related discipline, as well as demonstrate minimum levels of English proficiency.

Master’s degree programs in Iraq are usually two years in length (sometimes longer in professional fields), require the preparation of a thesis, and take 30 to 36 credits to complete. Study is conducted full-time; curricula are pre-set and concentrated in the area of specialization, except for certain foreign-language requirements. The first year requires course work, while the second year is usually dedicated to the preparation of the thesis. The minimum passing grade for a course is 60 percent, but the overall average for the first year must be 70 percent or above in order to proceed with the thesis.

Doctoral degrees in Iraq are terminal research degrees that require a minimum of three years of study. Programs include one year of coursework (at least 20 credits) and the preparation and defense of an original dissertation in the following two years. As is the case in master’s programs, the minimum passing grade for a course is 60, but the overall average in the coursework component must be 70 percent or higher. The name of the most commonly awarded final credential is the Doctor of Philosophy.

Bachelor’s degree holders who do not get admitted directly into master’s programs because they did not have high enough scores may have the option to enroll in higher diploma programs, where students can usually get admitted with a score lower than 65 percent. Programs are commonly one year in length, although higher diploma programs offered in professional disciplines may be up to three years. After completing the higher diploma, students may then continue their studies in master’s programs, but will not get exemptions or transfer credit based on their previous studies.

Professional Education

Professional education programs in Iraq are long first-degree programs that are usually entered directly after completion of secondary education, respectively the award of the Preparatory Certificate. The first professional degree in medicine, for example, is the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery, a six-year program studied at public medical colleges under the purview of the Ministry of Higher Education and Research. Programs include four years of coursework in basic sciences and pre-clinical study, followed by two years of clinical practice. After graduation, students are further required to complete a mandatory postgraduate clinical internship of two-year duration at a public hospital. Specialist doctors need to also complete residency training in a medical specialty. Requirements in other professions, such as dentistry or veterinary medicine are similar. Candidates must earn a first professional degree and fulfill additional postgraduate practice requirements.

Teacher Education

Secondary school teachers in Iraq must hold a bachelor’s degree in education, which is a four-year degree earned at universities. Holders of general bachelor’s degrees may alternatively earn a teaching qualification by completing a one-year higher diploma in education. The Diploma in Primary Education offered by teacher training institutes until recently is currently being phased out, so that elementary school teachers will soon be required to have a bachelor’s degree as well.

Higher Technical and Vocational Education

Higher technical and vocational education in Iraq is offered by Technical Institutes and Technical Colleges under the umbrella of Technical Universities. While technical institutes only offer two-year technical diploma programs, technical colleges also offer 4-year bachelor’s degrees in applied fields. Until recently, there were 16 stand-alone technical colleges and 28 technical institutes that were directly overseen by the Foundation of Technical Education (FTE), an organization under the purview of the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. In 2014, however, all technical colleges and institutes were absorbed by four new technical universities established under the FTE. In the Kurdistan region, technical colleges and institutes that were formerly under the FTE were in 2012 merged into three polytechnic universities overseen by the Kurdish Ministry of Higher Education.[12]Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, KRG http://www.mhe-krg.org/

Technical and vocational study programs are usually applied in nature, designed to prepare for employment, and include a large practical training component (curricula comprise of about 60 to 70 percent practical training and 30 to 40 percent theoretical classroom instruction). The top 10 percent of graduates from 2-year technical diploma programs may be eligible to continue their education in bachelor’s programs in a similar major at universities. Holders of a technical diploma will, in this case, usually be exempted from the first year of the bachelor’s program.

*At the graduate level the minimum passing grade for a course is 60% and an overall average grade of 70% is required to complete the degree

Known Challenges for Credential Evaluation

The 12+4+2 year benchmark education system of Iraq closely resembles the U.S. system and is not overly complex. The biggest challenge for credential evaluation, thus, is the authentication of documents. Students that are already abroad often face difficulties in requesting transcripts to be sent directly to foreign institutions. Many Iraqi institutions do not send transcripts by mail; they instead hand students stamped and sealed envelopes containing the academic record. Since it is usually not possible to request records online, many students in this scenario have to ask someone in Iraq to go to the school on their behalf to obtain the school-sealed envelopes.

It is good practice to closely examine academic records, as fraud does sometimes happen. Admissions officers are advised to double-check the records against school websites and/or documents submitted by other applicants from the same institution to compare logos, stamps, signatures, names of faculty members, and signatures, as well as compare names and GPAs of graduates for each year of study against the information listed on university websites, where provided. When in doubt, it is also good practice to verify academic records with the issuing institution. Note that it often takes a considerable amount of time until schools respond to verification requests.

Public universities located in conflict areas are currently operating in alternative locations (see the list of public universities on the Ministry of Higher Education’s website). This means that official documents can still be acquired from these universities, even though the main campus may be located in a war zone or be otherwise inoperational.

Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- Photocopy of Baccalaureate Examination Certificate issued in English by the Ministry of Education – submitted by the applicant (WES verifies documents with the Iraqi Ministry of Education).

Higher Education

- Photocopies of all diplomas or degree certificates issued in English by the institutions attended – submitted by the applicant.

AND

- Academic transcripts showing all subjects completed and all grades awarded for all post-secondary programs of study – sent directly to WES by the institution attended or submitted in an institution sealed/stamped envelope.

- For completed doctoral programs, a letter confirming the awarding of the degree – sent directly to WES by the institution attended or submitted in an institution sealed/stamped envelope.

- Precise, word-for-word English translations for all documents listed above not issued in English.

For further details, see the WES website.

Sample Documents

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Preparatory Certificate (Iraq, Central)

- Baccalaureate Examination Results (Kurdistan Region)

- Technical Diploma

- Bachelor of Science

- Higher Diploma

- Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery

- Master of Science

- Doctor of Philosophy

References

| ↑1 | According to the CIA World Factbook (2017). Estimates on the percentages of religious groups vary, depending on the source. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers that may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. |

| ↑3, ↑4, ↑7, ↑8, ↑9 | Ministry of Education www.moedu.gov.iq |

| ↑5 | Ministry of Education, General Directorate of Curricula www.manahj.edu.iq |

| ↑6 | NUFFIC. (2015). The Iraqi education system described and compared with the Dutch system. |

| ↑10 | Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research http://mohesr.gov.iq/ |

| ↑11 | See: Law of the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of 1988 (amended). |

| ↑12 | Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, KRG http://www.mhe-krg.org/ |