Education in Ethiopia

Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

This education profile describes recent trends in Ethiopian education and student mobility and provides an overview of the structure of the education system of Ethiopia. Note that some websites linked as sources in this article may be intermittently inaccessible.

An Introduction to Modern Ethiopia

Ethiopia is the second-most populous country in Africa after Nigeria with a population of 105 million. It’s also one of the least developed countries (LDCs) in the world, ranked 173rd among 189 countries on the United Nations’ Human Development Index. Like other low-income countries in Africa, Ethiopia presently faces the enormous challenge of creating a more inclusive and efficient education system amid rapid population growth. Compared with other sub-Saharan African countries, Ethiopia has been successful in slowing population growth and now has a relatively low fertility rate by African standards, but its population will nevertheless swell to an estimated 191 million people by 2050.1 More than 40 percent of the population is currently under the age of 15.

Despite Ethiopia’s booming economy, the country’s education system remains underdeveloped and plagued by low participation rates and quality problems—a situation partially owed to Ethiopia having been deprived of economic development for decades. As the World Bank has noted, Ethiopia was “one of the most educationally disadvantaged countries in the world” for much of the 20th century, because of armed conflict, famines, and humanitarian crises.

Bordering Djibouti, Eritrea, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan, Ethiopia is situated in a region of the world that is politically highly unstable. It has suffered from political violence and radical political changes in its recent history. After decades of absolute monarchical rule, a pro-Soviet socialist military junta called the Derg (the Committee)2 ousted Ethiopia’s late Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974 – an event that was followed by 17 years of civil war and brutal political repression until the Derg regime was eventually overthrown in 1991.

At the same time, Ethiopia fought several wars against Somalia and the annexed region of Eritrea, which gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993 after 30 years of warfare. By conservative estimates, between 1 million and 1.5 million Ethiopians died between the mid-1970s and the early 1990s, most of them killed in Ethiopia’s civil war.

Contemporary Ethiopia—formally called the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia—has come a long way since these dark times, even though hunger crises and separatist insurgencies continue to erupt in places like the Ogaden region, predominantly inhabited by ethnic Somalis. It’s important to understand that Ethiopia is an ethnically and regionally highly diverse country inhabited by over 80 different tribes and ethnic groups speaking more than 70 mother tongues.

The Oromos constitute the largest ethnic group, making up an estimated 34 percent of the population, and are primarily concentrated in the southwestern lowlands. They are followed by the Amharas (about 27 percent)—a group from the central highlands. Other larger groups are the Tigrayans and Somalis, both making up some 6 percent, as well as the Sidamas (4 percent), which are mostly situated in the South. Slightly more than 43 percent of Ethiopians identified as Coptic Christians and 34 percent as Muslims in Ethiopia’s latest 2007 census.

All said, the multi-ethnic Ethiopian federation remains fragile, but has become a politically somewhat more stable and economically much more dynamic country over the past two decades. Like other African autocracies, present-day Ethiopia is an authoritarian state with limited political and press freedoms. It has been ruled by the same political coalition: the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) – since 1991.

In recent years, Ethiopia has been rocked by mounting unrest and anti-government protests. According to Human Rights Watch, “security forces … killed over 1,000 people and detained tens of thousands during widespread protests against government policies” since late 2015. However, in a surprising move, the EPRDF in April 2018 instated a reformist prime minister, Abiy Ahmed. The new government quickly lifted the country’s state of emergency, freed political prisoners, eased Internet censorship, and announced hitherto unseen revolutionary reforms like the preparation of free and fair elections. But as sweeping as these measures are, it remains to be seen how the political situation in Ethiopia will evolve amid lingering political conflicts.

A Country in Transition: Rapid Economic Growth in the 21st Century

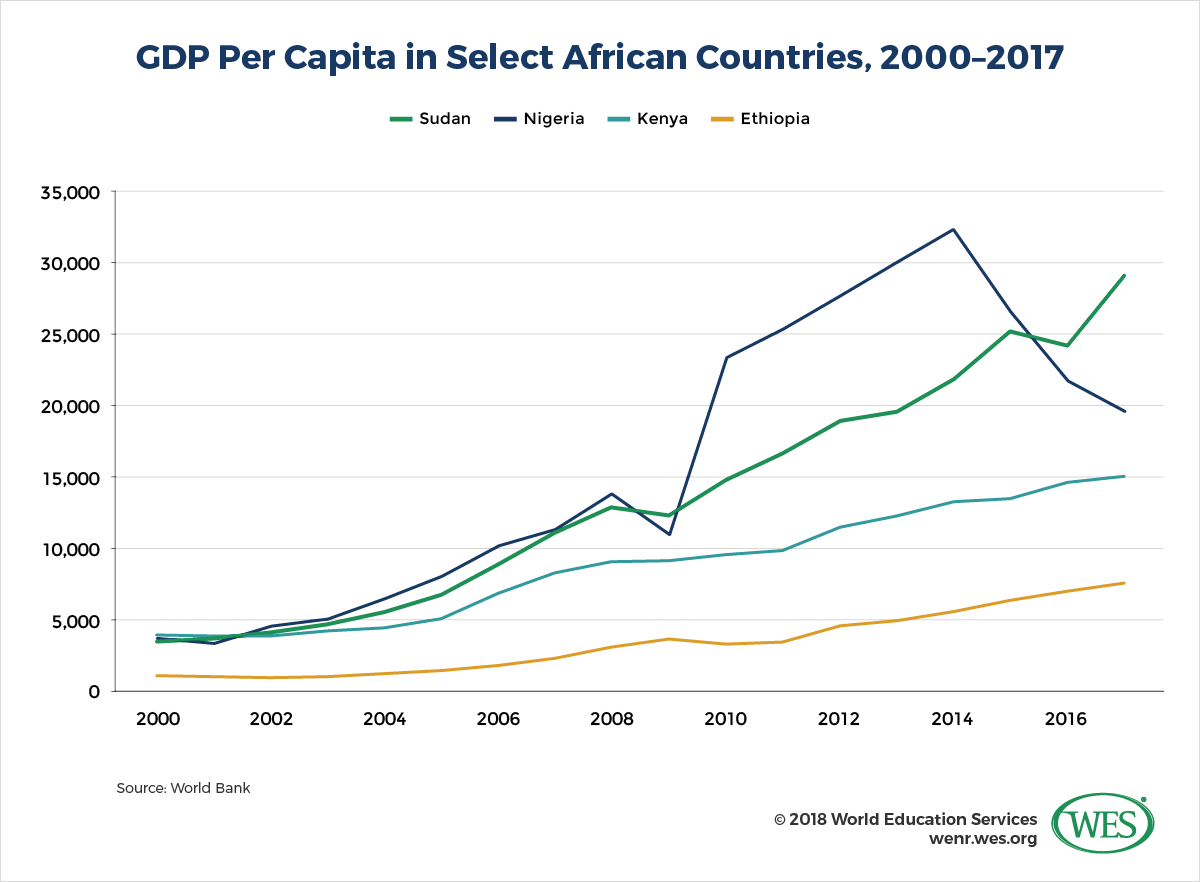

Economic development under the EPRDF regime has been impressive. It ushered in a free market economy, albeit one with strong socialist elements and a high degree of government intervention – a model that has proven so successful that observers now call Ethiopia an “African Tiger Economy.” By most accounts, Ethiopia has the fastest growing economy in Africa with gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates averaging 10 percent over the past decade. Between 2004 and 2017, GDP per capita grew more than fivefold, from USD$136 to USD$768, while the number of Ethiopians living on less than USD$1.25 a day dropped to 31 percent as of 2011 (down from 56 percent in 2000, according to the World Bank).

The country is now awash with large-scale infrastructure projects, ranging from the construction of Africa’s largest hydroelectric power dam to new highways and an electric railway system that links landlocked Ethiopia with Djibouti’s Red Sea port. Remarkably, in 2015 the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, opened a new urban light rail system for service—the only such system in sub-Saharan Africa outside of South Africa. There are even plans to launch a domestic-made satellite into space.

Critics argue that recent GDP increases have been mostly driven by these public infrastructure projects, rather than by broad-based economic growth. In fact, financing for many of the new construction projects, including the light rail system and the railway line to Djibouti, wasn’t raised domestically, but mostly bankrolled by loans from China. However, private direct investment from other countries is also rising and Ethiopia’s manufacturing sector is expanding. There are now hopes that Ethiopia could become Africa’s powerhouse for labor-intensive manufacturing, attracting foreign investors with lower labor costs than in countries like Vietnam or Bangladesh.

That said, underneath the prestigious construction projects, Ethiopia remains a desperately poor LDC in which 68 percent of the population works in agriculture. The country is heavily dependent on development aid and plagued by major problems like child malnutrition, high child mortality rates and incidence of communicable diseases, inadequate health care services, and severely limited access to electricity and sanitation systems. It’s not uncommon for schools to lack the most basic facilities, particularly in rural regions: More than three-quarters of elementary schools and basic education centers did not have access to electricity in 2015.3 Much larger investments in areas like health care and education will be necessary to elevate living conditions and develop human capital.

A Brief History of Education in Ethiopia

Traditionally, education in Ethiopia was religiously based and provided in church schools and monasteries to the elite few, mostly males. Modern Western education did not arrive in Ethiopia until the 20th century and developed only slowly. Merely 3.3 percent of the elementary school-age population attended school in 1961 – back then one of the lowest enrollment ratios in Africa. Unlike in other African countries, where European colonial rulers imposed modern education systems patterned after their own, Ethiopia’s education system evolved – technically speaking – indigenously. Discounting a short period of military occupation by Italy from 1936 to 1941, Ethiopia is the only country in Africa that was never colonized.

However, Ethiopia’s education system was nevertheless intrinsically shaped by external influences. To compensate for the lack of qualified personnel in Ethiopia, Ethiopia’s imperial government imported teachers, administrators, and education advisors from countries like France and Egypt. It also invited foreign private schools into the country when it attempted to build a more modern education system in the early 20th century. French was the language of instruction at many Ethiopian schools until 1935.

After World War II, efforts to create a modern mass education system intensified, but this time under the influence of education advisors from Britain and the United States. During this period, school curricula were British, and English was promoted as the language of instruction in secondary schools. Ethiopia’s higher education system, likewise, was initially developed with extensive foreign involvement. Following the 1950 establishment of Addis Ababa University as Ethiopia’s first HEI, a handful of colleges were established throughout the decade, most of them administered and primarily staffed by Western expatriates.4 It was not until the early 1970s that the higher education system became more “Ethiopianized.”

Under the Marxist-Leninist Derg, education policies became influenced by education advisors from Communist countries like the Soviet Union and East Germany. While the Derg politicized education and used it for ideological indoctrination, it did make progress in increasing elementary enrollment rates. It also launched a large-scale program to increase literacy—the campaign won international praise and decreased the national illiteracy rate despite the civil war.5 In higher education, by contrast, entry rates declined sharply notwithstanding the opening of more HEIs. Education spending per tertiary student decreased in favor of military spending, and many academics fled the country.6

Growth of the Education System

Ethiopia’s education system expanded rapidly in the decades after the overthrow of the Derg in 1991. The net enrollment rate (NER) in elementary education, for instance, jumped from only 29 percent in 1989 to 86 percent in 2015, according to the UIS. Ethiopian government statistics report that the number of elementary schools tripled from 11,000 in 1996 to 32,048 in 2014, while the number of students enrolled in these schools surged from less than 3 million to more than 18 million. In secondary education, overall enrollment is much smaller, but growing modestly nevertheless: The NER in upper-secondary education grew from 16 percent in 1999 to 26 percent in 2015 (UIS).

The higher education sector, likewise, has come a long way since its humble beginnings. There were just three public universities, 16 colleges, and six research institutions in 1986 enrolling fewer than 18,000 students.7 Today, there are 30 public universities, as well as a growing private sector. Ethiopia did not have a single privately owned tertiary institution before the early 1990s, but there are now 61 accredited private HEIs. The overall number of tertiary students in both public and private institutions exploded by more than 2,000 percent, from 34,000 in 1991 to 757,000 in 2014, per UIS data.

However, despite this expansion, Ethiopia still trails other LDCs in key education indicators. In fact, the rapid growth over the past decades has overburdened the system and created a slew of new problems, such as funding shortages and a deterioration of quality. Enormous progress in increasing access to education notwithstanding, some observers now consider the Ethiopian education system to be in a state of crisis, and that quantitative achievements in areas like elementary enrollments mask stagnation in terms of quality and learning outcomes.

Ethiopia’s adult literacy rate of 39 percent (2012), for example, is still one of the lowest in the world and far below the LDC average of 77 percent (in 2016, per UIS). Marked disparities in participation in education also persist between rural areas and urban centers, most notably Addis Ababa, as well as between low-income households and more affluent demographic groups, and between boys and girls. School drop-out rates are among the highest in the world: Just slightly more than 50 percent of enrolled children complete elementary education. Participation rates also fall off markedly at higher levels of schooling—Ethiopia’s upper-secondary NER remains fully 17 percentage points below the current LDC average (UIS).

In the tertiary sector, educational quality is strained by scarce funding, poor facilities and infrastructure, overcrowded classrooms, insufficient levels of academic preparedness among students, and a shortage of qualified teaching staff. Only 15 percent of university instructors had doctoral degrees in 2015. Many students were taught by young, inexperienced instructors holding just a bachelor’s degree. Research funding and outputs are consequently very low, so that Ethiopia ranks below other African countries like Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, or Uganda in comparative studies that measure research and innovation, such as the Global Innovation Index.

High and growing unemployment among Ethiopian university graduates, meanwhile, raises questions about the quality and relevance of academic curricula, which are considered ill-suited for current labor market demands. There are also great disparities in quality between public universities and a growing number of smaller private for-profit providers, many of them said to be of dubious quality. Former Prime Minister Meles Zenawi in 2010 went as far as accusing private HEIs of “not only providing substandard education but ‘… practically just printing diplomas and certificates and handing them out.”8

Crucially, access to tertiary education in Ethiopia remains severely constrained: While participation rates in higher education now exceed those of other East African countries like Tanzania or Uganda, Ethiopia’s tertiary gross enrollment ratio of 8.1 percent (2014) is below the LDC average and less than half that of neighboring Sudan (UIS). Also, tertiary education in Ethiopia remains elitist. Participation rates are highly skewed toward men from financially well-off households; women made up only 30 percent of all tertiary students in 2014 (UIS).

International Student Mobility

Little information exists on international student mobility to and from Ethiopia. There are no publicly available statistics on inbound mobility, but it can be assumed that the number of international students in Ethiopia is small, given that the poverty-stricken, conflict-ridden country hardly has the reputation of an international study destination and does not have notable high-quality universities.

Nevertheless, the Ethiopian government and institutions like the World Bank incentivize students from sub-Saharan countries to study at institutions like Addis Ababa University with limited scholarship programs. It’s possible that substantial numbers of African students, particularly those from worse-off, neighboring countries like Somalia, are enrolled in Ethiopian higher education institutions (HEIs), but that’s speculative given the absence of concrete data. Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia’s flagship institution and largest university, enrolled only 120 international students in 2016. Mekelle University, another large public university, had 88 international students as of 2017.

Outbound student flows from Ethiopia are small as well, if growing. As per the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS), the number of Ethiopian students enrolled in degree programs abroad doubled from 3,003 in 1998 to 6,453 in 2017. To put this number into perspective, however, there are currently 89,094 Nigerians, 14,012 Kenyans, and 12,988 Sudanese studying in degree programs at foreign universities.

This gap is likely owed to a lack of disposable income in Ethiopia. Except for Nigeria, which has roughly twice as many tertiary students, Ethiopia has more tertiary students than both Kenya and Sudan and consequently a larger pool of potential international students. However, Ethiopia has a considerably lower per capita income and fewer middle-income households able to afford an overseas education. According to one survey of Ethiopian international students, a majority of them previously attended private and international secondary schools—a sign that they’re from affluent urban households. But even these students appear to be largely dependent on scholarship funding: 72 percent of surveyed students were on full scholarships and another 11 percent on partial stipends.

Ethiopia has a tradition of out-migration and brain drain dating back to the rule of the Derg, when many of Ethiopia’s professionals and intelligentsia fled the country to escape persecution and violence. By some accounts Ethiopia lost as much as 75 percent of its skilled workforce during that time.

Out-migration has since continued, not only driven by political violence but also by the scarcity of employment opportunities and stiff barriers to social mobility in Ethiopia. This trend has resulted in the emergence of large Ethiopian diaspora communities in countries like the United Kingdom and the United States, where Ethiopians are now the largest African immigrant group after Nigerians. These trends are also reflected in the motivations of Ethiopian international students: According to the above-cited survey, most students believe that studying abroad enhances their employment prospects and gives them a competitive edge in the labor market by obtaining a better education than is possible at home.

The U.S. is the most popular destination country among Ethiopian degree-seeking students, accounting for 24.5 percent of international enrollments, per UIS data. Beyond the U.S., Ethiopian international students are dispersed in smaller numbers over a variety of countries, including Finland, India, Italy, Norway, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey.

There’s no UIS data available for China, but the country has become a top study destination for Ethiopians in recent years. China is Ethiopia’s largest trading partner by far and actively promotes academic exchange through university partnerships and scholarship programs. In 2018 alone, the Chinese government provided more than 1,450 scholarships for Ethiopians, most of them for short-term vocational training, but also for graduate programs at Chinese universities. According to Chinese figures, the number of Ethiopian students enrolled in degree and non-degree programs in China more than tripled since 2011 and stood at 2,829 in 2016. (Note that these numbers are not directly comparable to UIS data, since they rely on a different method for counting international students).9

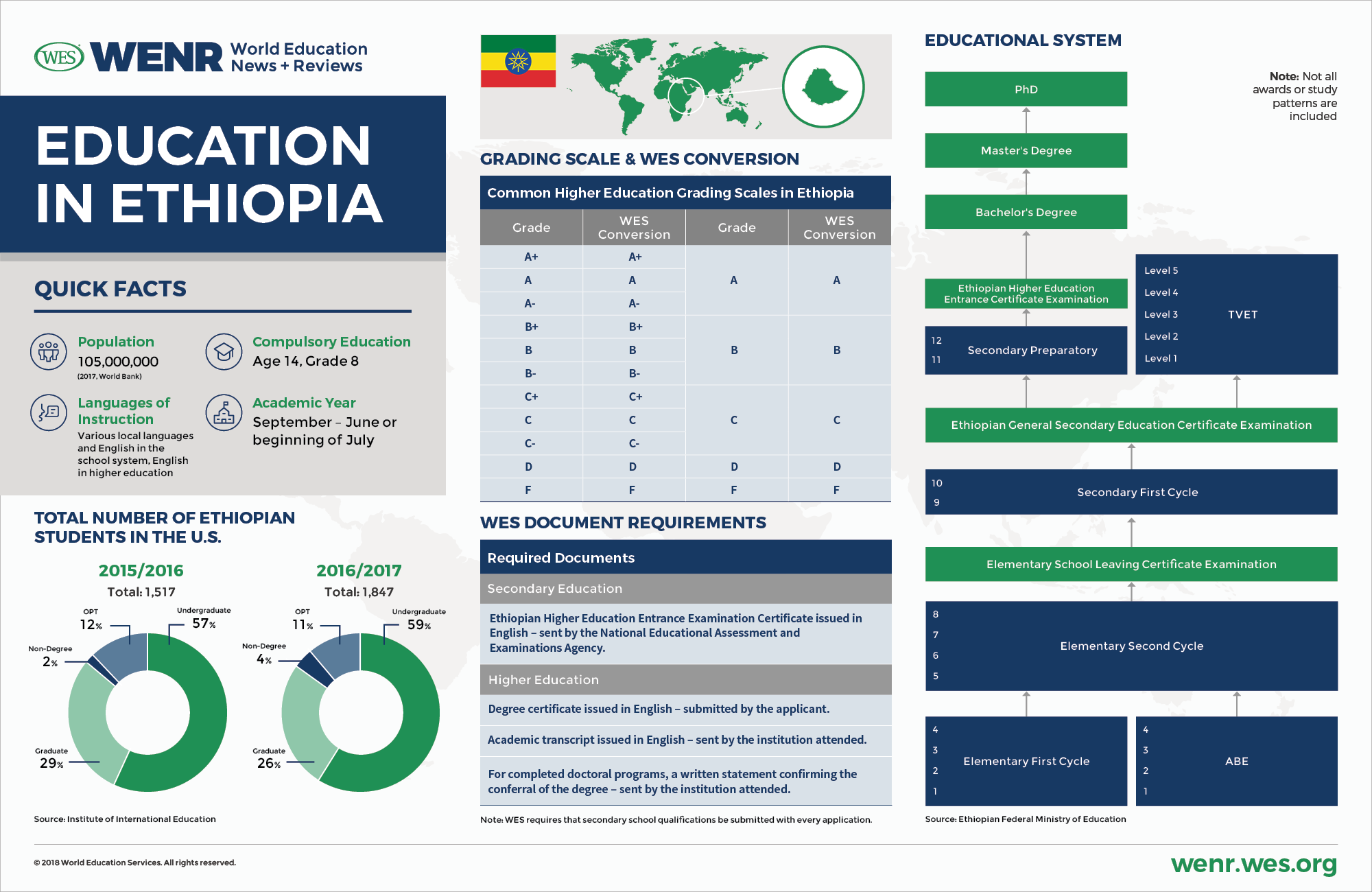

In the U.S., the number of Ethiopian students peaked at 2,120 students in 1984/85 before declining until the early 2000s, as per the Open Doors data of the Institute of International Education. Inbound flows from Ethiopia have since fluctuated, but are generally on an upward trajectory. Between the 2007/08 and 2016/17 academic years, the number of Ethiopian students in the U.S. increased by 40 percent from 1,316 to 1,847 students. The majority of Ethiopian students – 59 percent – are enrolled at the undergraduate level compared with 26 percent at the graduate level and 15 percent in Optional Practical Training and non-degree programs. In Canada, the number of Ethiopian students has doubled over the past decade, but remains small with 405 students in 2017, according to government data.

Ethiopia’s Education System

Administration of the Education System

Ethiopia is a federation of nine regional states delineated by ethnicity, as well as two cities designated as separate administrative units or “chartered cities” (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa). After the fall of the Derg regime, Ethiopia’s government pursued a deliberate policy of decentralization, including the devolution of education administration to the regions. School education is now mostly administered by local authorities in subdistricts or woredas within the individual regions, a move designed to better accommodate local needs.

Funding is shared between the regions and the federal government, which provides about 50 to 60 percent of the funding through non-itemized block grants to regional governments, as well as grants given directly to schools. To ensure consistency, the federal government manages the education system with multi-year development programs that set performance targets and reform agendas for the entire system. School curricula are standardized nationwide. Schools use a national curriculum framework that includes textbooks developed by the General Education Curriculum Framework Development Department of the federal Ministry of Education (MOE).

The federal MOE in Addis Ababa oversees and funds Ethiopia’s higher education, exercising far-reaching control over public institutions. The autonomy of public HEIs is limited, since the MOE sets admission standards, enrollment quotas, and curricula; systematically curtails academic freedoms; and frequently appoints university administrators based on political allegiance.10 Private HEIs are regulated less tightly, but must be accredited by the Higher Education Relevance and Quality Agency (HERQA), a nominally autonomous body under the purview of the MOE. Quality control in technical and vocational education and training (TVET) is provided by a federal TVET agency, which the MOE also oversees.

Language of Instruction and Academic Calendar

Amharic is Ethiopia’s official language alongside English and the dominant language in major cities, government agencies, and the media. However, since it’s spoken as a mother tongue by only about 30 percent of Ethiopians, the language of instruction used in elementary education varies greatly by region. Languages used include Oromo, Amharic, Somali, Tigrinya, and at least 10 additional languages. English is introduced as a medium of instruction between grades five and eight, depending on the region, and is the sole language of instruction in secondary and higher education.

The Ethiopian school year runs from September to the end of June or the beginning of July. Universities usually have two semesters of 16 weeks each. When reviewing academic documents from Ethiopia, it’s important to note that the country follows its own ancient calendar, which can be difficult to understand. The Ethiopian year begins on September 11 and has 13 months: 12 months of 30 days and another month of five days (six days in a leap year, which occurs every four years). As a rule of thumb, Ethiopian calendar years are approximately seven or eight years behind Western calendar years, that is, November 1, 2018, is Tikimt (February) 22nd 2011 on the Ethiopian calendar. The easiest way to convert dates is to use an online conversion tool. Academic documents often indicate both the Ethiopian and Western (Gregorian) calendar dates, but sometimes they don’t.

Elementary Education (Basic Education)

The Ethiopian school system consists of eight years of elementary education, divided into two cycles of four years, and four years of secondary education, divided into two stages of two years (4+4+2+2). Education is technically compulsory for all children until grade eight, but actual participation in elementary education is far from universal. Low enrollment rates, particularly in rural areas, and widespread attrition are two reasons why. According to government statistics from 2011, 20 percent of children dropped out as early as grade two, and only about 50 percent of pupils remained in school until grade eight.

Prior to entering elementary education, pupils can attend kindergartens, which are mostly run by non-governmental organizations, faith-based organizations, and other private providers. However, the availability of preschool programs varies considerably by region and is extremely limited in some areas. The number of children attending kindergarten is still small, but growing quickly—the nationwide GER in preschool education was 39 percent in 2015 (up from 5.2 percent in 2011).11

Elementary education is provided free of charge at public schools, as well as by fee-charging private schools, which tend to have better facilities and better-educated teachers. About 7 percent of elementary schools were private as of 2012/13, most of them located in Addis Ababa. Private providers in the capital charge monthly tuition fees anywhere from a few dollars to more than USD$75, in addition to other fees for registration and teaching materials, putting these schools out of reach for poor households. There are also a number of international schools in Addis Ababa that charge exorbitant tuition fees by Ethiopian standards and therefore cater only to wealthy elites and expatriates. The overall share of enrollments in private schools among all elementary enrollments was 5 percent in 2015 (UIS).

Most pupils enter elementary education at the age of seven, although there are a sizable number of overaged children in Ethiopia’s schools. The majority of public schools don’t have formal entry requirements, but private schools often have selection mechanisms in place, such as interviews and examinations.

As stated earlier, the core curriculum is standardized nationwide, but there are some variations, including the language of instruction, at the local level. The subjects taught in the first stage (grades one to four) are Amharic, mother tongue, English, mathematics, environmental science, and arts and physical education. The second stage (grades five to eight) includes the same language subjects, mathematics and physical education, but also features civics, integrated science, social studies, and visual arts and music, as well as biology, chemistry, and physics in higher grades.

Promotion is based on continual assessment during the first phase, while term-end examinations are introduced in the second phase. At the end of grade eight, pupils sit for a region-wide external examination and are awarded a Primary School Leaving Certificate, which is a prerequisite for admission into secondary school. Pupils who fail the exams need to repeat grade eight before they can retake the test.

Alternative Basic Education

Given the high number of out-of-school children in rural regions, Ethiopia has an alternative basic education (ABE) system in place to educate underserved children, mostly from pastoral communities, outside of the formal school system. ABE affords children in critical areas the opportunity to study the first-stage elementary curriculum on flexible class schedules that are adjusted to accommodate traditional ways of living. Classes are set up mostly in rudimentary local ABE centers and makeshift mobile schools that rely on local intra-communal instructors. ABE allows marginalized children to receive at least a basic, foundational education. Upon the completion of ABE, children can transfer into the second cycle of elementary education at regular schools. There were 821,988 children enrolled in ABE programs nationwide in 2011. In addition to ABE, radio broadcasts and pre-recorded audiocassettes and videotapes are used to provide educational programming.

Secondary Education

Participation in secondary education in Ethiopia is mostly a privilege of affluent households in urban areas. Enrollments in rural regions accounted for only 11.2 percent in lower-secondary education and 3.6 percent in upper-secondary education as of 2011. Overall enrollments in secondary education in the nation of 105 million people are remarkably low by international standards. There were only around 795,000 students enrolled in upper-secondary education in 2015, compared with 982,000 students in Afghanistan and one million in Sudan, both of which are countries with considerably smaller populations. Until very recently (UIS), merely 10 percent of Ethiopian youths in relevant age cohorts participated in upper-secondary education.

The first stage of secondary education in Ethiopia is referred to as general secondary education and lasts for two years (grades nine and 10). There are no entrance examinations at public schools, and education is tuition-free until grade 10, whereas upper-secondary students have to pay school fees. Private education is still nascent in general secondary education, where less than 5 percent of students are enrolled in private schools, but the share of private enrollments jumps pointedly to around 15 percent at the upper-secondary stage (2015, per UIS).

The general secondary curriculum covers three languages (mother tongue, English, and Amharic), mathematics, information technology, civics, biology, chemistry, physics, geography, history and physical education. The language of instruction is English, which can represent a challenge since the English-language abilities of both teachers and students tend to be limited.

At the end of grade 10, students must sit for the nationwide external Ethiopian General School Leaving Certificate Examination (EGSLCE), a multiple-choice test federally administered by the National Educational Assessment and Examination Agency. The EGSLCE usually includes nine test subjects, graded on an A-E letter grading scale. To qualify for progression into upper-secondary education, students must pass at least five subjects with a grade of C or higher. Failure rates in the exam are relatively high with about one-third of test takers failing in 2015.12

Depending on their grade average, students who pass can continue in the university-preparatory upper-secondary track, or enroll in vocational programs (discussed below). The government currently prioritizes technical training and seeks to stream the majority of grade 10 graduates into vocational education programs amid capacity shortages in higher education: In 2013/14, 45 percent of graduates transitioned into vocational education, while 30 percent to 35 percent of students continued in the university-preparatory track.

Upper-Secondary Education (Preparatory Secondary School)

University-preparatory education lasts two years (grades 11 and 12) and is open to all holders of the EGSLCE with sufficiently high grades. Students can choose between a natural science track and a social science track. Both streams have a common core curriculum that makes up 60 percent of the study load and includes English, civics, information communications technology, mathematics, physical education and an elective language (Amharic or local languages). The courses taught in the natural sciences track are biology, chemistry, physics, and technical drawing, whereas the social science track covers geography, history, economics, and business.

At the end of grade 12, students sit for the nationwide external Ethiopian University Entrance Examination (EUEE), which tests their knowledge in seven subjects, including mathematics, English, civics, general academic aptitude, and three stream-related specialization subjects. The examinations are quite demanding: In 2017, only 41 percent of the 285,628 students who sat for the examinations scored high enough to be admitted into university. Exam performance is graded on a numerical 0–100 point scale with a total possible score of 700 in the seven test subjects combined. Cutoff scores for university admission vary by year depending on the number of available seats, but a minimum overall grade average of 295 was required for admission to higher education in 2017 (see also the section on university admissions below).

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

The majority of Ethiopian students who continue education after grade 10 enroll in TVET programs, of which there are a great variety offered by both public and private providers. These programs range from informal short-term training courses to formal certificate programs lasting between one and three years. The Ethiopian government has recently undertaken heightened efforts to standardize TVET by developing official vocational competency standards and a TVET qualifications framework. Strengthening vocational training is a top priority as the country seeks to expand its manufacturing sector and advance the employability of Ethiopian youth.

As of lately, the TVET sector has expanded rapidly with annual growth rates averaging 30 percent between 2004 and 2009, but the supply of training programs is still vastly insufficient to accommodate the surging demand. According to government statistics, there were 352,144 students enrolled in formal programs in 2015 (up from 191,151 students in 2007). More than 75 percent of these students were enrolled in private institutions.

The current TVET system was codified in a 2011 TVET law and is overseen by a dedicated federal TVET agency which develops model curricula and sets overall training standards. Regional TVET agencies or education bureaus have some leeway to customize the curricula to accommodate local industry needs. Private providers must seek accreditation from regional authorities and apply for re-accreditation every three years.

Grade 10 graduates can enroll in TVET programs at public or private colleges and training centers, as long as they meet set minimum grade thresholds in the EGSLCE exams, which vary by year and region depending on the number of available slots. Training is free at public institutions for recent secondary school graduates, but older students and those attending private institutions pay tuition fees. Private for-profit providers are primarily located in urban areas and tend to have better facilities, but do not necessarily provide better training.

Secondary-level TVET qualifications are grouped into four categories (I-IV), depending on the length and complexity of the program: Level I programs last one year, level II programs two years, and level III and level IV programs, three years, with level IV programs being designed to prepare students for supervisory roles in the workforce.

Upon graduation, students earn a certificate of completion of middle level technical and vocational education and training. However, students must also pass an external vocational skills test to earn a formal, nationally recognized certificate of competency or national qualification certificate. The federal TVET agency has developed training curricula for at least 379 vocations, but Ethiopian TVET providers offered only 197 of these curricula as of 2012. Common fields of study in TVET include agriculture, construction, business, information technology, manufacturing, hospitality, nursing, and midwifery. Students can progress sequentially from level I to level IV programs, and external candidates who have adequate work experience may also obtain a certificate of competency by taking the vocational skills assessment test without completing a training program.

TVET curricula are highly applied rather than theoretical, and include a practical training component of 70 percent that comprises a mandatory industrial internship. Theoretical instruction makes up only 30 percent and incorporates a general education component (mathematics, English, civics, and business). Holders of level III and level IV certificates can apply for admission into university programs after two years of employment and may receive advanced standing in some fields.

In addition to upper-secondary TVET programs entered after grade 10, there are “basic” and “junior” TVET programs that can be entered upon completion of elementary education and provide a pathway to middle level programs. At the post-secondary level, TVET colleges and some HEIs offer vocationally oriented diploma programs classified as level V, which require a level III/IV certificate or the EUEE for admission and are mostly two years in length, although one-year and three-year programs also exist. These programs are primarily designed to prepare students for specialized employment, but study completed in applied diploma programs may sometimes be transferred into bachelor’s degree programs at universities.

Higher Education

University Admissions

Ethiopia has a centralized admissions system in which undergraduate admissions criteria are set by the federal MOE for all HEIs, public and private. Admission is generally based on the EUEE and is highly selective, given the scarcity of university seats. Each academic year, the MOE sets minimum grade requirements and quotas for different programs based on the number of available seats, which means that concrete requirements vary from year to year. The government’s objective over the past years has been to steer 70 percent of students into engineering and natural science programs and 30 percent into the humanities and social sciences. Cutoff grades for admission into public universities are higher than for private institutions, so that public HEIs receive the best students, while lower-performing students tend to be funneled into the private sector.

The minimum EUEE grade average to enroll in any higher education program was 295 in 2017, but the grade cutoff for admission into natural science programs at a public HEI was significantly higher at 352, while admission into social science programs required an average of 335. Disadvantaged groups are granted preferential admission via lower GPA requirements. For example, female students needed only a score of 320 to qualify for admission into social science programs—a threshold lowered even further for women from pastoral communities and other special needs regions, which required an average of only 300. That said, these measures have had limited impact thus far on diversifying Ethiopia’s student population, which continues to be dominated by mostly male, affluent students from urban areas (only 35 percent of undergraduate students and 24 percent of graduate students were female in 2015).

As mentioned above, alternative entry pathways exist for holders of TVET certificates of competency (level III or higher) after two years of employment. Additional university entrance examinations may be required in disciplines like architecture, medicine, veterinary medicine, or pharmacy.

Higher Education Institutions

Ethiopia’s higher education ecosystem has not only grown and diversified rapidly over the past few decades, it is bound to expand exponentially in the years ahead, driven by factors like population growth, rising income levels, and climbing upper-secondary enrollments. In 2013 the British Council projected that the number of tertiary students in Ethiopia will increase by an additional 1.7 million by 2025.

In light of these trends, the federal government in 2015 greenlighted the construction of 11 new universities; Ethiopia is now on the verge of having 44 operational public universities (up from 30). Private sector enrollments, meanwhile, have fluctuated and flattened in recent years after surging rapidly since the 1990s. However, private HEIs enrolled at least 15 percent of undergraduate students in 2015,13 and the private sector still has tremendous potential for growth. Notably, foreign distance education providers like the University of South Africa and India’s Indira Gandhi National Open University have also begun to offer programs in Ethiopia, either independently or in collaboration with Ethiopian providers.

The size and scope of public universities in Ethiopia varies significantly, but a majority are multi-disciplinary institutions that offer undergraduate and graduate programs while concentrating on providing mass education rather than research. Public universities are directly funded by the federal government, although they raise part of their revenues from modest fees for tuition and on-campus housing. Addis Ababa University is the country’s largest and most preeminent HEI with 48,673 students and 70 undergraduate and 293 graduate programs. Another reputable public research university with more than 40,000 students is Jimma University located in the Oromia region.

Ethiopian universities trail institutions from other East African countries in terms of international reputation. They are not included in standard world university rankings, such as the Times Higher Education ranking of Africa’s best universities, which features both Uganda’s Makerere University (ranked in fifth position) and the University of Nairobi.

In addition to public universities, there are 32 public teacher training colleges , as well as a number of public institutions supervised by other federal government ministries, including military academies and the Ethiopian Civil Service University.

Private institutions tend to be smaller for-profit colleges specializing in fields like business administration and computer science and information technology, as well as allied health fields and nursing. Most private providers enroll not more than a few thousand students and offer only undergraduate programs. Just a handful of institutions, such as St. Mary’s University, offer master’s programs. There are presently 61 accredited private HEIs, predominantly clustered in Addis Ababa.

Most private HEIs have sprung up over the past 15 years and don’t have the best reputation in Ethiopia. While there are a number of quality providers, several are considered to be substandard, profit-driven, institutions with poor facilities whose unqualified teaching staff teach curricula directly copied from other institutions. While such claims cannot be verified independently, Wondwosen Tamrat, a professor at St. Mary’s University, alleges that some institutions also obtained accreditation by fraudulent means, yet circumvented scrutiny because they’re protected by powerful patrons in Ethiopia’s government.

Another quality-related problem stems from Ethiopia’s centralized admissions system which steers top students into public institutions, so that private HEIs absorb mostly less-qualified students who get locked out of the public system. As one university administrator put it, “students we admit are in some way “leftovers” because the best ones (with highest scores) will go to public institutions.”14 As in many other African countries, private HEIs in Ethiopia are demand-absorbing institutions unable to effectively compete with public providers.

Accreditation and Quality Assurance

To address quality problems in the mushrooming private sector, Ethiopia created an accreditation body in 2003—the Higher Education Relevance and Quality Agency (HERQA)—and made it mandatory for private institutions to obtain accreditation. The federal government establishes and oversees public universities, so they do not have to seek accreditation. However, they are required to have internal quality assurance systems and regular internal quality audits. HERQA monitors compliance with these requirements. The MOE also ensures that public universities advance national reform objectives by tying funding to the implementation of these goals.15

Private HEIs are not allowed to operate in Ethiopia unless they obtain a HERQA accreditation certificate for their programs and submit to quality audits by HERQA. Institutions first apply for a pre-accreditation permit and receive accreditation after one year of operation, as long as their programs satisfy HERQA’s requirements. Institutions have to submit a self-evaluation report which is evaluated in the form of multi-day on-site quality audits. HERQA assesses management structures, infrastructure, learning resources, curricula, academic assessment methods, promotion and graduation rates, research output, and other criteria.16 HEIs have to apply for re-accreditation after three years, after which accreditation is given for five-year periods. Accreditation is granted for a specific set of programs, for which HERQA may stipulate enrollment quotas and permissible modes of delivery (that is, regular versus part-time or distance education modes). Lists of accredited institutions and programs are available on the HERQA website.

HERQA has helped improve quality standards in Ethiopia—its establishment alone caused a number of low-quality private providers to close down rather than seek accreditation in the early 2000s. In a sign of heightened emphasis on quality in recent years, HERQA in 2011 shut down five private HEIs and placed another 13 on probation. At the same time, HERQA has been criticized for not being autonomous enough and vulnerable to political intervention, having inadequate staffing and infrastructure, as well as low quality thresholds, and nontransparent and sometimes erratic decision-making processes. The MOE in 2010 barred private HEIs from offering distance education programs over quality concerns, only to revoke the ban a few months later, presumably because it affected too many students and instructors.

Education Spending

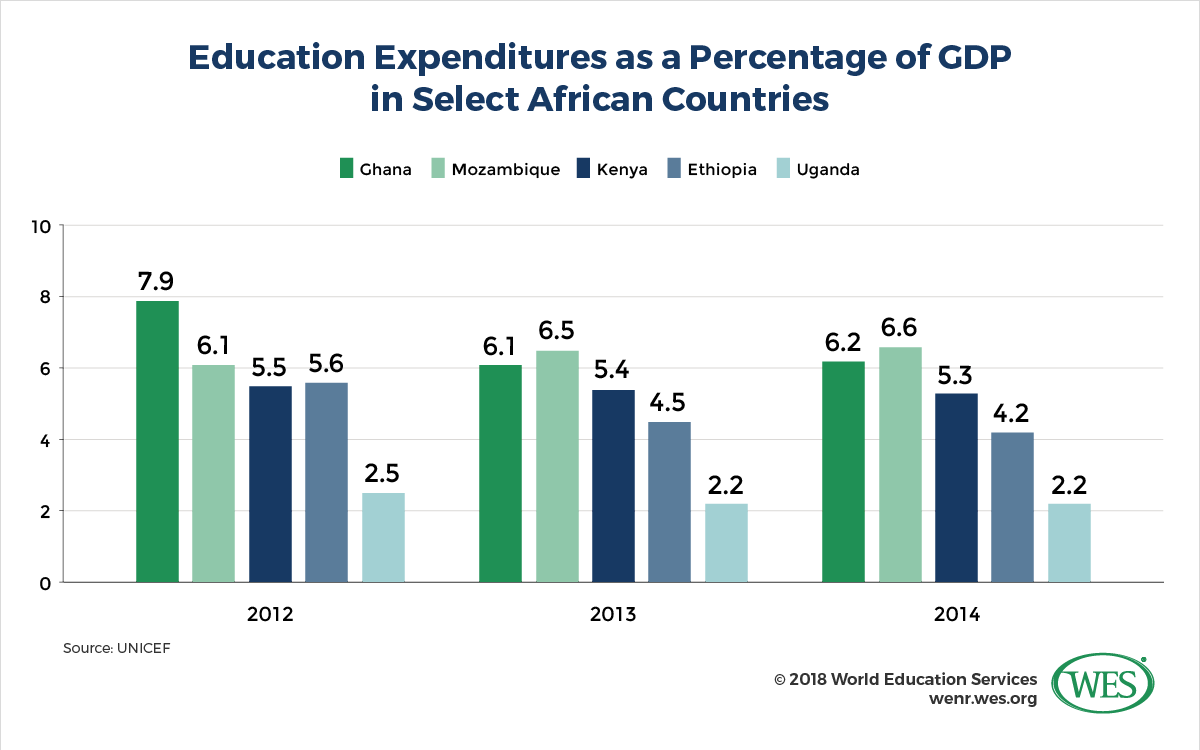

Ethiopia’s government considers education a fiscal priority, but struggles to keep up with the expansion of the system and the surging number of students: Spending per tertiary student as a percentage of GDP per capita, for instance, dropped by more than 50 percent between 1997 and 2012. Nominal education spending has increased strongly in recent years with public education expenditures tripling from 21.6 billion Ethiopian Birr in 2009/10 (USD$780 million at current conversion rates) to 67.9 billion Birr (USD$2.45 billion) in 2015/16. However, when adjusted for Ethiopia’s high inflation rate, which averaged 16 percent between 2006 and 2018, real value gains were only modest and spending remains relatively low by African standards. Education expenditures as a share of GDP have fluctuated over the past 15 years: They increased from 4 percent in 2000 to a peak of 5.6 percent in 2012, before dropping back down to 4.2 percent in 2014, according to World Bank figures.

The Ethiopian government spent 24.2 percent of its overall expenditures on education in 2015/16, making education the largest item in the federal budget. While that’s a considerable percentage compared with the education spending of other emerging economies, observers consider current spending levels insufficient to drive further expansion while ensuring quality standards. A high percentage of education spending—48 percent in 2014/15—is devoted to tertiary education, which is largely consumed by the construction of new universities. Beyond that, a sizable share of expenditures goes to recurring expenses like teacher salaries, limiting the availability of funds for structural improvements in critical areas like the school system. Compared to other African countries, teacher salaries in Ethiopia are high in relative terms, that is, when measured as a percentage of GDP per capita. Corruption represents another challenge—while less widespread than in other countries in the region, there’s a risk of “leakage” in the downstream distribution of funds in some parts of the system, according to the World Bank.

Higher Education Credit System and Grading Scales

The credit systems and grading scales used by Ethiopian HEIs resemble those found in the U.S., although it should be noted that Addis Ababa University and several other universities recently began to use the European ECTS credit system. At most public universities, one credit unit is defined as one contact hour per week taken over a span of 16 weeks. The common minimum credit requirement in most four-year bachelor’s programs is 128 to 136 credits (16 or 17 credits or 30 ECTS per semester), whereas a three-year degree can be completed with a minimum of 102 to 108 credits (180 ECTS). Students who have earned a high enough GPA may be allowed to graduate in a shorter period of time by taking more credits per semester.

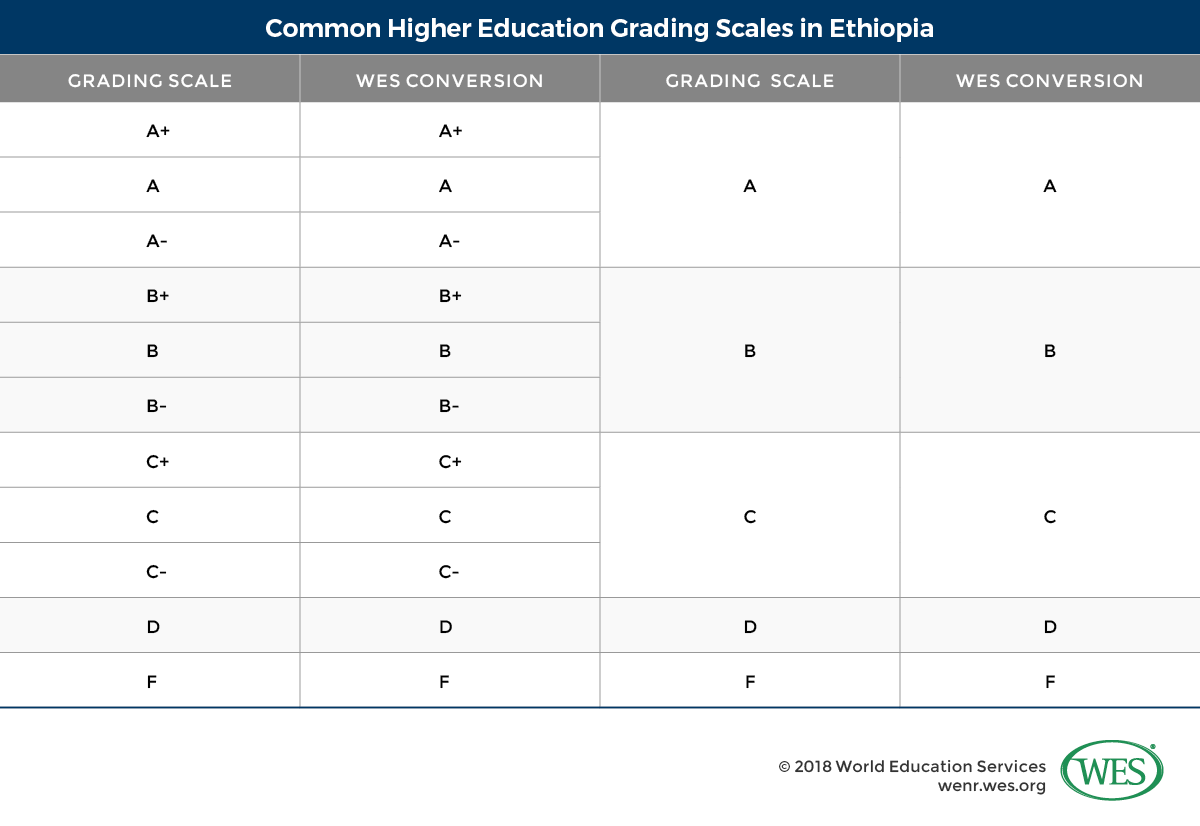

Grading scales resemble the standard U.S. A-F scale with some institutions using a simplified version without the “+” and “-” designations (see two common variations listed below). A minimum cumulative GPA of 2.0 (C) is usually required for graduation from bachelor’s programs, whereas master’s programs require a cumulative GPA of 3.0 (B).

The Tertiary Degree Structure

Ethiopia’s standard tertiary degree structure includes three- and four-year bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. The overwhelming majority of Ethiopian students (about 95 percent) are enrolled in undergraduate programs: There were 729,028 undergraduate students in 2015 compared with only 37,152 students in master’s programs and 3,135 students in doctoral programs. Only 24 percent of graduate students were women. The most popular fields of study in undergraduate programs at public institutions were engineering and technology, business and economics, and the social sciences and humanities. At private institutions, more than 50 percent of students studied business and economics, followed by health sciences, engineering, and technology. At the graduate level, social sciences and humanities were the most popular disciplines overall.17

Diplomas

Until the 2000s, universities used to award two-year diplomas (12+2) and three-year advanced diplomas (12+3) in a variety of academic disciplines, such as history, biology, or engineering. Many of these diploma programs were part-time programs for students who didn’t quite meet degree admission requirements.

Today, diploma programs are more narrowly defined as TVET qualifications taught by TVET providers, so that these programs have been phased out at public universities, although some HEIs still offer applied diploma programs in fields like accounting or business administration. The old academic diploma programs, as well as some of the new TVET diplomas may be partially transferred into bachelor’s programs, depending on the program and institution.

Bachelor’s Degree

All bachelor’s degree programs in standard academic disciplines used to be four years in length and included a preparatory year designed to prepare students for higher education. However, in 2003 the preparatory year was eliminated and its content incorporated into upper-secondary curricula – preparing students for tertiary education is now a function of upper-secondary education.

Today, bachelor’s programs are three or four years in length and lead to the award of a Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science, although other-named credentials like the Bachelor of Business may also be awarded by some institutions. The majority of current bachelor’s programs in social sciences, humanities, and business offered by Addis Ababa University are three years in length. Curricula are usually specialized with few, if any, general education requirements. Some programs may be studied in part-time (evening) or distance education mode over an extended time period of up to six years. These programs are typically referred to as extension programs and indicated as such on academic transcripts.

First degree programs in professional disciplines like engineering, law, architecture, pharmacy, medicine, or dentistry, on the other hand, are either five or six years in length and conclude with the award of credentials like the Bachelor of Laws, Bachelor of Pharmacy, or Doctor of Medicine (see also the section on medical education below).

Master’s Degree

Admissions standards for master’s programs are less strictly defined than undergraduate admissions criteria, and they are set by individual universities. That said, admission into master’s programs typically requires a bachelor’s degree in a related discipline with high enough grades and a passing score in a program-related entrance examination, as well as other aptitude tests and an English proficiency examination in some cases. Master’s degree programs commonly last two years (30–36 credits), although one-year, one-and-one-half-year, and three-year programs also exist. Most of them require the preparation of a thesis (or graduation project), but there are also non-thesis options, which have higher credit requirements. The standard credentials awarded are the Master of Arts and Master of Science.

Doctor of Philosophy

The Doctor of Philosophy is a terminal research degree that is earned after a minimum of three or four years of advanced graduate study. A master’s degree in a related discipline is the standard admission requirement, but in some programs students can also be admitted on the basis of a bachelor’s degree with high grades. Additional entry requirements may include entrance examinations, the submission of a research proposal, or English proficiency exams. Most programs include a course work component of two or more semesters and conclude with the defense of a dissertation written in English.

Medical Education

The standard entry-to-practice qualification in medicine, the Doctor of Medicine, is earned upon the completion of a long, single-tier undergraduate program of six-years’ duration. Medical curricula include a six-month pre-medical component (general sciences) and pre-clinical studies during the first two years, followed by three years of clinical studies, concluding with a qualifying examination. Students are required to complete a one-year clinical internship in the final year.

Ethiopia has a severe shortage of medical doctors, particularly in rural regions, and suffers from a high degree of out-migration of medical professionals. To stem this brain drain and expand health services throughout the country, all medical school graduates are currently mandated to register with the Ministry of Health of Ethiopia and work as general practitioners for two to four years before they can specialize. Certification in medical specialties requires another three to four years of clinical training at teaching hospitals, concluding with the award of a Certificate of Specialization or Specialist Diploma.

Ethiopia is currently expanding its medical training system. In 2012, 13 new medical schools opened in the country, boosting enrollments in medical programs to 3,100 students. Another reform designed to alleviate Ethiopia’s shortage of physicians is the New Innovative Medical Education Initiative (NIMEI). Adopted in 2012, NIMEI ushered in a shorter and revised 4.5-year medical curriculum intended for holders of bachelor’s degrees in health and natural sciences. These programs are offered by 10 universities and three teaching hospitals. To get admitted, applicants must pass a national medical entrance examination—a test that includes both written and oral components and is administered by the NEAEA.

Teacher Education

Ethiopia’s teacher training system is currently in flux with reforms being implemented at varying speeds in different parts of the system. Elementary schoolteachers are trained at 32 public teacher training colleges under federal supervision, as well as at private institutions. Admission is based on the EGSLCE (completion of grade 10). All teachers in elementary education are presently required to complete a three-year (10+3) training program and earn a diploma in elementary education. Until recently, it was possible to teach at the lower-elementary level (grades 1-4) upon earning a one-year (10+1) teaching certificate, but these programs are being phased out, and certificate holders are expected to upgrade their qualifications.

Secondary schoolteachers are required to hold at least a bachelor’s degree. Until lately, teachers earned a dedicated bachelor’s degree in education at universities and some teacher colleges, but the system is currently being changed to require teachers to complete a postgraduate teacher training program on top of a bachelor’s degree in another discipline. Since 2011, Postgraduate Diploma in Teaching programs have been created at several universities. They are one year in length and combine instruction in pedagogical subjects with a school-based internship. Institutions like Addis Ababa University also offer master’s degrees in education, and the government intends to make a master’s degree mandatory for upper-secondary teachers. However, Ethiopia is in dire need of teachers and faces enormous challenges in training enough qualified instructors. A substantial number of teachers in the country’s schools continues to teach without the required minimum academic qualifications.

WES Document Requirements

Secondary Education

- Ethiopian University Entrance Examination Certificate issued in English—sent by the National Educational Assessment and Examinations Agency

Higher Education

- Degree certificate issued in English—submitted by the applicant

- Academic transcript issued in English—sent by the institution attended

- For completed doctoral programs, a written statement confirming the conferral of the degree—sent by the institution attended

Note: WES requires that secondary school qualifications be submitted with every application.

Sample Documents

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Ethiopian University Entrance Examination Certificate

- National Qualification Certificate (TVET Level III)

- Bachelor of Arts (3 years)

- Bachelor of Science (4 years)

- Doctor of Medicine

- Master of Science

- Doctor of Philosophy

1. Medium variant projection by the United Nations.

2. “Derg” is a short name for the “Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces, Police and Territorial Army.” While that name was later rejected, members of the Derg under its leader, Dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam, continued to rule the country, so that the government of that time period is colloquially referred to as “the Derg.”

3. Ministry of Education, Education Statistics Annual Abstract, 2007 E.C. (2014/15), Hamle, 2016, p. 61.

4. Molla, Tebeje: Higher Education in Ethiopia: Structural Inequalities and Policy Responses (Education Policy & Social Inequality), Springer, Singapore, 2018. Kindle Edition, Kindle location 772.

5. Government statistics from the time reported that the national literacy rate was 83 percent in 1989, but this number seems unrealistically high and cannot be verified independently.

6. Molla (2018), Kindle location 856.

7. Molla (2018), Kindle Location 843.

8. Quoted from: Yirdaw, Arega. The Role of Governance in Quality of Education in Private Higher Education Institutions: Ethiopia as a Case Study, Addis Ababa, 2015. Kindle Edition, Kindle Location 572.

9. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers which may raise questions about discrepancies. The data of the UNESCO Institute Statistics generally provides the most reliable point of reference for comparisons between different countries, since it is compiled according to one standard method. It should be pointed out, however, that it only includes students enrolled in tertiary degree programs. It does not include students on shorter study abroad exchanges, or those enrolled at the secondary level or in short-term language training programs.

10. Molla (2018), Kindle Location 1375, 1040 following.

11. 2015 number from: Ministry of Education (2016), p. 28.

12. Ministry of Education (2016), p. 88.

13. The percentage of private enrollments is likely higher, since the government statistics cited here don’t include complete data for all private institutions. (Ministry of Education (2016), p. 147)

14. Quoted from: Yirdaw (2015), Kindle location 2360.

15. Molla (2018), Kindle location 3870, Yirdaw (2015), Kindle location 562.

16. Yirdaw (2015), Kindle location 992.

17. See: Ministry of Education (2016), pp. 147-167.