Traditional Chinese Medicine: Surging International Interest and a Shifting Educational Landscape in China

Claire Mengshi Zheng and Jee Lee, Credential Analysts

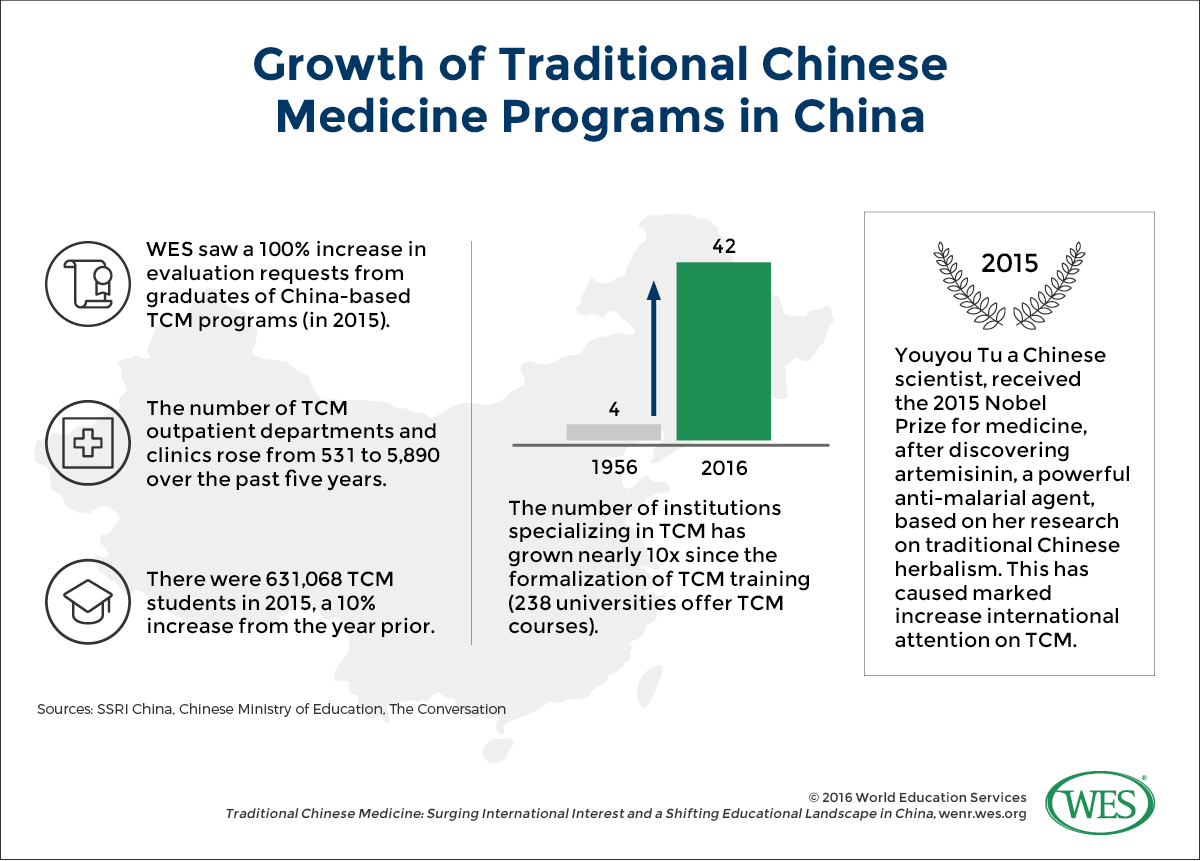

In 2015, World Education Services witnessed an almost 100 percent increase in applications from students seeking evaluations of credentials in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) earned in China. And the number keeps growing. International students seem to be increasingly looking to China for education in TCM practices, rather than enrolling in TCM programs offered in other countries.

As we began to observe this emerging trend, we started asking a few questions. Among them:

- What’s behind the rise?

- What does the TCM education landscape in China look like?

- What types of programs do credential evaluators and licensing organizations need to be aware of as they review and validate the qualifications issued by various programs and institutions?

International Interest in China-based TCM Programs: What is the Scope and Why Are Numbers Rising?

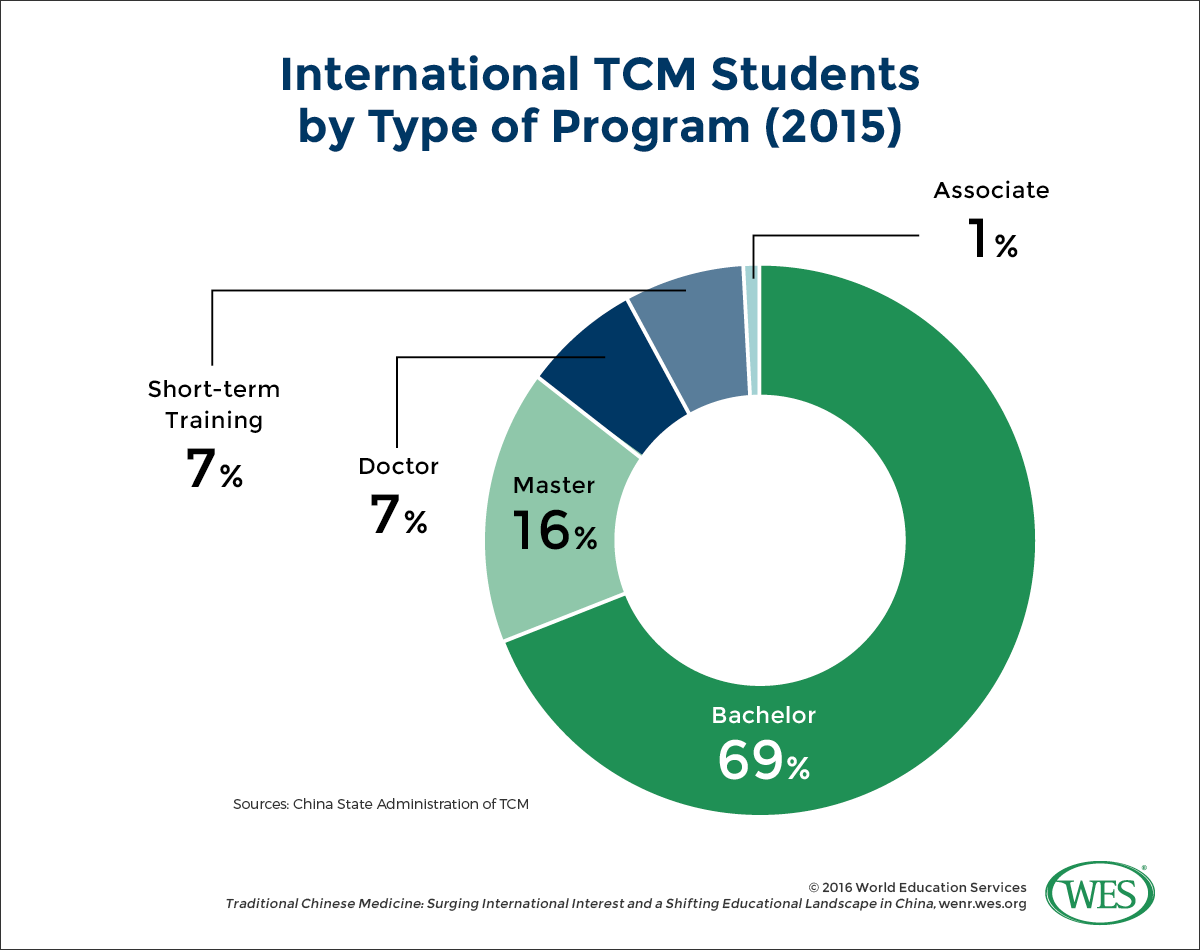

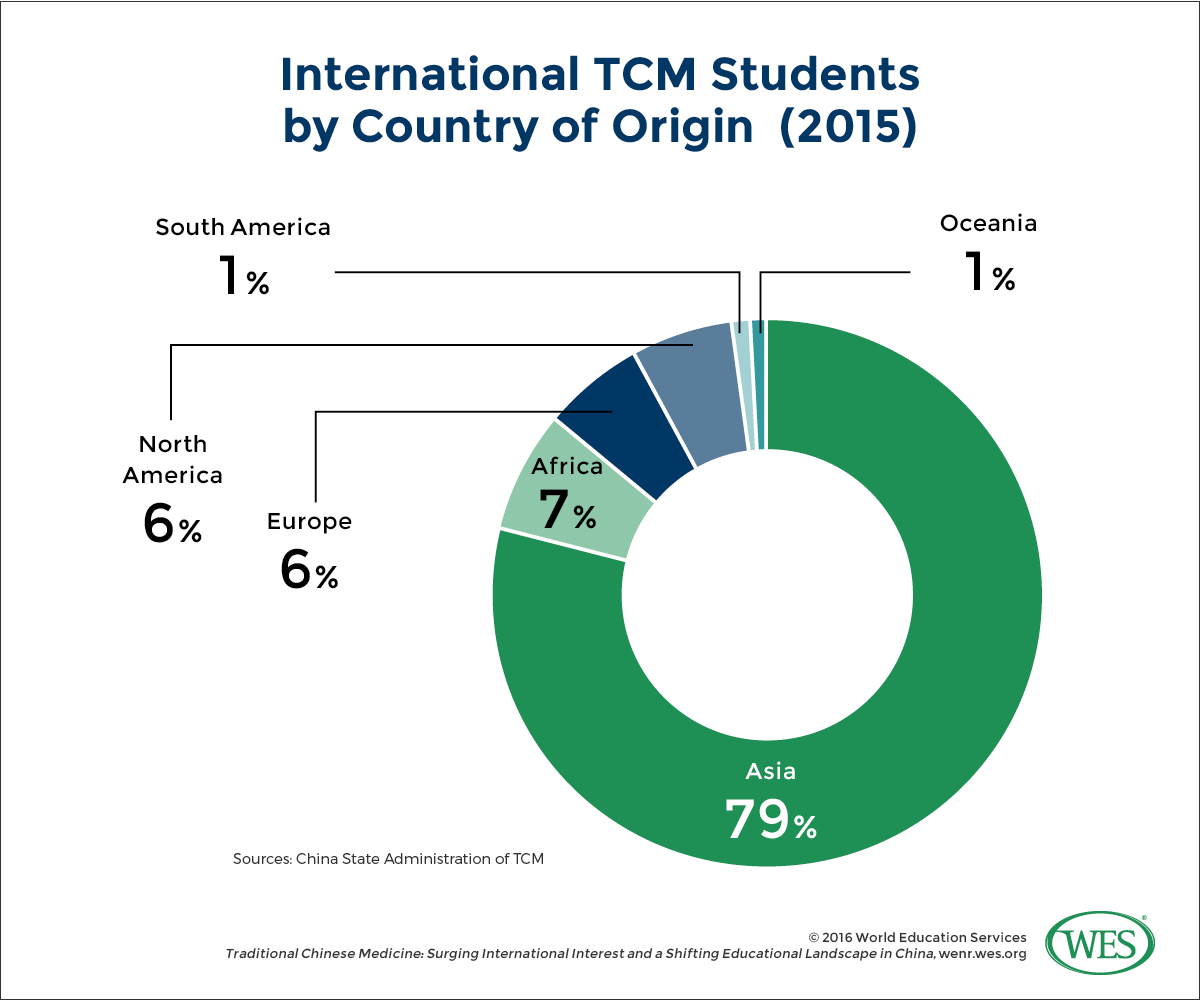

More than 700,000 students presently study TCM in China. In 2015, 5,510 of these students were international. (The majority were from other Asian nations). According to the Chinese State Administration of TCM, most international students enroll at the bachelor’s level, and an overwhelming 89 percent of the international students fund their own education.

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact reasons why more international students are seeking TCM education in China, but several factors – both in and outside of China – likely contribute. One may be a spike in public awareness of TCM that accompanied Chinese scientist Youyou Tu’s receipt of the 2015 Nobel Prize for medicine. Tu discovered a powerful anti-malarial agent, artemisinin, based on her research into traditional Chinese herbalism. The Nobel committee’s recognition of her work represented a watershed for the field. “Traditional medical knowledge anywhere in the world has not even been on the radar for Nobel Prize prospects,” noted Marta Hanson, a history of medicine professor at Johns Hopkins University. “Until now, that is.” Tu’s award, she and others have noted, is part and parcel of a larger trend toward looking for the scientific roots of ancient remedies as antibiotics begin to lose their potency.

Parallel Tracks to the Future: China Pushes for More International Students and an Expanded TCM Sector by 2020

The pull to China, as opposed to other countries where TCM training is available, has its roots in multiple places, of course. One is almost certainly China’s effort to position itself, via its “Study in China” initiative, as a major destination for international students by 2020. Another is likely the Chinese government’s recognition that TCM is a substantial economic engine: In 2014, the total reported value of TCM was, per the director of the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, roughly $110.8 million USD (730 billion RMB). Seeking to spark further growth, China’s government recently introduced a 15-year plan for the development of the TCM sector. The plan, according to the China-centric publication Sixth Tone, “sets ambitious goals for the industry, saying that it should become one of the major pillars of the Chinese economy and provide 30 percent of the medical industry’s gross output by 2020.”

China’s status as ground zero for TCM also gives it enormous pull. In a study published in 2011, researchers evaluating TCM in a local and international context called TCM education in China more “authentic.” Moreover, they noted, TCM education in other countries tends to focus primarily on acupuncture, and to neglect other key aspects of practice, such as materia medica and herbal pharmacology.1

Growing Professional Opportunities for TCM Practitioners in a Key Market: The U.S.

In the U.S., demand for qualified TCM practitioners is on the rise. One critical reason is the increased mainstream acceptance of “complementary” or “integrative” health interventions. These integrative approaches pair conventional Western-style medicine with other, non-Western techniques that focus on “the full range of physical, emotional, mental, social, spiritual and environmental influences” which play a role in a patient’s well-being. Well-respected institutions, including the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the Cleveland Clinic, and others, all have integrative medicine centers that include herbal clinics, massage therapy, acupuncture, and more. In June 2016, the 25-year-old National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) unveiled its latest strategic plan. The plan explicitly calls out the need for additional research into TCM practices such as acupuncture to help patients who, “[d]espite medical treatment… continue to experience troublesome levels of symptoms and a diminished quality of life.”

One other significant factor in the U.S. demand for qualified TCM practitioners may also be a nationwide opioid epidemic, which has pushed emergency room visits, overdoses deaths, and associated costs to record levels. In the last year especially, the U.S. government has pressed hard for a programmatic solution to chronic pain management that does not rely on opioids. In March 2016, the Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee (IPRCC), which includes representatives from U.S. agencies such as the Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Food and Drug Administration, National Institutes of Health, and members of the public, including scientists and patient advocates, released a National Pain Strategy. The strategy recommends, among other solutions to chronic pain management, “the development of a system of patient-center pain management practices” that include TCM techniques, most prominent among them, acupuncture.

One other significant factor in the U.S. demand for qualified TCM practitioners may also be a nationwide opioid epidemic, which has pushed emergency room visits, overdoses deaths, and associated costs to record levels. In the last year especially, the U.S. government has pressed hard for a programmatic solution to chronic pain management that does not rely on opioids. In March 2016, the Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee (IPRCC), which includes representatives from U.S. agencies such as the Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Food and Drug Administration, National Institutes of Health, and members of the public, including scientists and patient advocates, released a National Pain Strategy. The strategy recommends, among other solutions to chronic pain management, “the development of a system of patient-center pain management practices” that include TCM techniques, most prominent among them, acupuncture.

The upshot of all of these factors seems to be an increase in the professional opportunities available to licensed TCM practitioners. At the same time as demand has risen, however, the academic landscape around TCM in China has become more complex, creating challenges for those seeking training as well as for employers and licensing organizations seeking to verify the credentials of incoming practitioners.

Western Interest in TCM

TCM is booming beyond mainland China, and some institutions see explicit opportunity stemming from increased Western interest in the field. As the Taiwan-based China Medical School notes in its promotional materials for its School of Chinese Medicine:

“[The] development of applications and research in integrative medicine has been a fast-rising new trend in the medical world. The government of the United States dedicates a large sum every year to basic and clinical research in integrative and traditional medicine. Top universities in the U.S. such as Harvard University, Yale University, Stanford University, University of Pennsylvania, Duke University, Johns Hopkins University, University of Michigan, University of Virginia and University of California […] have all established integrative medical centers or complementary and alternative medical centers. These all require professionals and scholars in the field of integrative medicine as trained by this program”.

The school offers programs intended to prepare students either for a dual license in both Chinese and Western medicine, or a single license in Chinese medicine.

What Does TCM Education Look Like? And What Kinds of Qualifications Do Students Get?

In 1956, the China State Council established four colleges specializing in traditional Chinese medicine in four of China’s major cities: Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Chengdu. The year is viewed as a watershed in the formalization of TCM education in the context of Chinese higher education. Sixty years later, China has 42 mono-specialized TCM colleges/universities and 238 universities that offer TCM programs. Forty-six specialized universities offer master level programs and 17 offer programs at the doctoral level.

NOTE: Specialized TCM institutions tend to have TCM in the name, for example, Beijing University of TCM. These specialized colleges offer programs such as acupuncture, clinical Chinese pharmacy, nursing (TCM), integrative medicine (TCM combined with Western medicine), Chinese medicine classics (focusing on the literature part), et al. The other 238 universities, by comparison, are medical universities or general universities that also include TCM programs among their academic offerings. While the total number of general and medical universities with TCM programs is larger than the number of mono-specialized TCM colleges and universities, international students prefer to enroll at the 42 mono-specialized TCM institutions, according to China’s State Administration of TCM, the government agency responsible for the administration of traditional Chinese medicine.

Programs of Study: Bachelor’s, Master’s, Doctoral

Bachelor’s Level

Admissions Requirements for International Students

Most bachelor’s-level TCM programs for international students offer bilingual curricula in English and Chinese. A few schools also offer part of the curriculum in Japanese. Students are admitted based on  their high school GPAs and, depending on the language of instruction, their performance on standardized exams. If instruction is in Chinese, admission depends in part on performance on the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK) – an international standardized test that evaluates Chinese-language proficiency in an academic context. Non-native English speakers are granted admission to English language programs based on performance on the TOEFL or IELTS, both of which are used to evaluate English language proficiency in an academic context.

their high school GPAs and, depending on the language of instruction, their performance on standardized exams. If instruction is in Chinese, admission depends in part on performance on the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK) – an international standardized test that evaluates Chinese-language proficiency in an academic context. Non-native English speakers are granted admission to English language programs based on performance on the TOEFL or IELTS, both of which are used to evaluate English language proficiency in an academic context.

Some schools that cater to international students have additional admissions requirements. At Shandong University of TCM, for instance, applicants are first evaluated based on academic transcripts and HSK results. Those that make the first cut are then invited to sit for the school’s entrance examination.

Program Length, Curriculum & Structure

Most recognized bachelor programs in TCM require five years of study, but students have the option to finish in seven years. In general, graduates must complete 240-300 credits and roughly 1,000 hours of practice in a clinical internship. (The exception is Chinese herbal pharmacology, which is discussed in the sidebar that accompanies this section.) International students at the bachelor’s level are generally instructed separately from their Chinese peers.

The program is strictly structured – students have to take certain courses within certain semesters. Basic science and medical foundation courses comprise 30 percent of the curriculum. TCM theory courses, including the reading of Chinese TCM classics, make up 25 percent. Clinical practice courses such as TCM diagnosis, communication with patients, and clinical internships make up another 30 percent of the requirements. The rest of the courses are electives: students may choose to enhance their medical foundation knowledge, TCM practice skills, or even Chinese-language proficiency. The last year is reserved for the internship and graduation exams.

NOTE: As a sample curriculum, we have listed below the curriculum of the Shanghai University of TCM. The first year of study at this institution focuses heavily on foundational concepts and language courses.

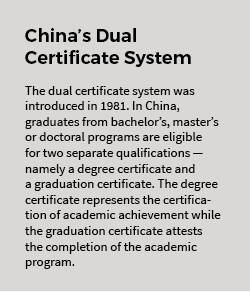

Bachelor’s degrees in TCM specialties – including acupuncture, moxibustion, tuina, or integrated medicine – have roughly similar curricular components, but the clinical courses emphasize the respective specialization. Upon graduation from recognized programs in these specialties, students obtain a Bachelor of Medicine in TCM. In China, the degree is recognized as a first professional degree; holders are permitted to practice TCM in mainland China. Five-year degrees from recognized institutions also meet the academic requirements for local TCM certification in most U.S. states.

Graduate-Level TCM Education

Master’s and Doctoral Programs

The most commonly recognized TCM degrees at the postgraduate level include the Master of Medicine and Doctor of Medicine in TCM. Both degree programs typically last three years. These higher level programs tend to cater to students interested in either research, or faculty positions. Most students who enroll have already studied and earned degrees in TCM at the bachelor’s level.

Instruction at both the master’s and doctoral levels tends to be offered in Chinese only. One reason is  that few international students enroll. (The minimum requirement for licensing in other countries is usually the completion of three or four years of study in TCM – a requirement that a bachelor’s degree in TCM easily addresses). In general, the few international students who do enroll in graduate-level programs study alongside their Chinese peers, with no differentiation in curricular requirements. Tianjin University of TCM is among the few schools that offer graduate-level programs in English.

that few international students enroll. (The minimum requirement for licensing in other countries is usually the completion of three or four years of study in TCM – a requirement that a bachelor’s degree in TCM easily addresses). In general, the few international students who do enroll in graduate-level programs study alongside their Chinese peers, with no differentiation in curricular requirements. Tianjin University of TCM is among the few schools that offer graduate-level programs in English.

Fast-Track Degree Programs

Some recognized programs allow students to complete a bachelor’s TCM degree, a master’s TCM degree, or a doctoral TCM degree as part of an integrated program. For instance, Beijing University of TCM’s fast-track, combined bachelor-doctoral program, called the Qihuang Guoyi program, allows students to complete both a bachelor’s degree and doctorate in nine years. Students have to complete five years of undergraduate study. In the fourth year, they may take an entrance examination in order to enroll directly in the doctoral program.

Other Chinese TCM-Training Models

Beyond the rigorous academic programs offered at mainstream and specialized institutions, TCM education is available through a number of additional venues, including vocational schools, online or “blended” programs, transnational partnerships between foreign institutions and Chinese institutions, self-study and more. Common models include:

- Higher secondary vocational schools: Practitioners of TCM are licensed at two levels in China: medical assistant and medical doctor. The minimum requirement for licensure as a medical assistant is a vocational high school diploma in a TCM field, followed by one year of clinical internship or apprenticeship training. Higher secondary vocational schools for TCM offer a three-year program that lead to a vocational high school diploma. These schools are, however, becoming increasingly rare.

- Higher vocational colleges: Higher vocational colleges offer a three-year junior college diploma course in TCM. Students afterwards normally enroll in a TCM bachelor’s degree program to meet the licensing requirements.

- Self-study programs: Self-study is a common form of study in China, although it is being increasingly phased out in the wake of the rapid expansion of China’s higher education sector. With more vocational colleges and universities in existence, many students no longer have to rely on self-study programs to gain access to the education they desire. Further limiting the usefulness of self-study programs in TCM is the fact that a policy change in the early 2000s excluded self-study programs from the eligibility requirements for licensing in TCM.

- Transnational programs based in China: The emergence of Sino-foreign transnational partnerships also plays a role in TCM education. According to a recent Ministry of Education report, institutions from 183 countries are collaborating with universities in China. Many have developed programs in TCM. An increasingly standard model among private U.S. institutions is a joint program that provides students with the opportunity to complete their study in China, in order to earn more advanced qualifications. The Florida-based Atlantic Institute of Oriental Medicine (ATOM), for example, has a program that allows candidates enrolled in their doctorate of acupuncture and oriental medicine (DAOM) program to study one additional year at Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (SHUTCM) to obtain a Chinese doctoral degree.

- Transnational programs based outside of China: Chinese universities have also begun setting up campuses in foreign countries. One early overseas TCM campus was set up in 2008 in Portugal, as a collaboration between Chengdu University of TCM and the Universidade de Évora. In 2015, Beijing-based Capital Medical University opened a campus in Canada. Students at this institution can obtain bachelor’s and master’s degrees in TCM, as well as a Doctor of Medicine in TCM. The Bachelor of Medicine program includes four years of academic study in Canada, followed by one year of clinical training in Beijing. Another Chinese institution, Xiamen University, has a campus in Malaysia offering a bilingual (Chinese and English) Bachelor of Medicine in TCM program. Similar to the aforementioned programs, students do coursework in Malaysia before completing their clinical training at affiliated hospitals in China.

- Blended learning at an accredited institution: Training in blended programs includes both on- and offline components. A few institutions offer blended programs that are fully accredited by the Chinese MOE. The Xiamen University, Department of TCM, for instance, offers distance learning programs catering to international students. The admission requirements and program structure are comparable to regular bachelor’s degrees in TCM. Students take classes online, but must complete the exams and internship in person. After completing the academic part of the program, students receive a graduation certificate. Once they complete their clinical internships and pass a final exam, they obtain a full-fledged bachelor’s degree in TCM.

- Blended learning at a non-accredited institution: Founded in 1999, Beijing Mebo TCM Training Center offers an example of this type of blended program in a non-MOE-accredited setting. The center offers blended-learning programs in TCM specialties, including herbal medicine and acupuncture. The online portion includes seven online courses, online textbooks and access to a personal tutor who can answer questions in both Chinese and English. Once the online portion is completed, the program requires that students attend in-person lectures and complete a clinical internship at the Wangjing Hospital, a Beijing TCM institution with which the school is affiliated. Upon completion of the online and in-person coursework, as well as the clinical training, Beijing Mebo students receive a certificate of completion issued by the Wangjing Hospital (which is affiliated with the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences). The school is not accredited by the Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE).

- Non-accredited short-term training: Besides recognized degree programs, some schools also offer non-degree short-term training programs in TCM. For instance, the Shanghai University of TCM offers two-year certificate programs in acupuncture and tuina.

1. Jiao, L., Liu, Y., Chen, Z., Guo, Y., & Wang, W. (2011, March). Local and International TCM Education Comparison. International Journal of TCM, 33(3), 257-259. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4246.2011.03.029