Georgia: A Post-Soviet Model for Fighting Academic Corruption

Beka Tavartkiladze, Director of Evaluation Services, WES Canada

Corruption-free higher education institutions play a significant role in forming a democratic and open society – post-Soviet Georgia is a case in point. However, Georgia’s road to having a transparent higher education system – one that has largely rooted out corruption – has not always been smooth. The journey, and lessons learned along the way, offer insight for other countries trying to minimize systemic corruption in academic and other parts of civil society.

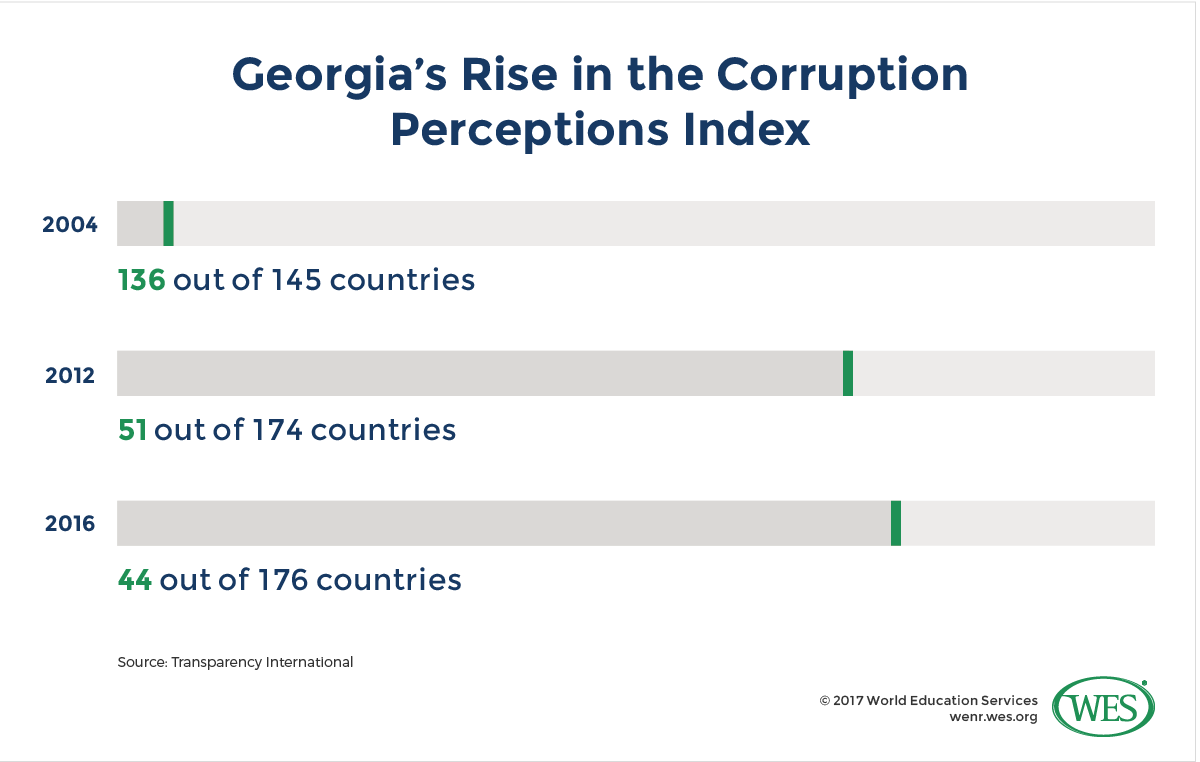

In the years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgia suffered from rampant corruption and was widely considered one of the most corrupt countries in the world. In 2004, the country was ranked 136th out of 145 countries included in Transparency International’s (TI) Corruption Perception Index.

Since then, however, the nation has made tremendous strides in reducing corruption. Political measures adopted after the 2003 Rose Revolution have curbed corruption in education and other public sectors. By 2012, Georgia had outperformed all other post-Soviet republics except for Lithuania and Estonia in reducing corruption and ranked 51st out of 174 countries in TI’s corruption index. By 2016, the country’s ranking further improved to 44 out of 176.

That is not to say that challenges have disappeared altogether. High-level corruption among politicians and nepotism in the hiring of civil servants, for instance, are lingering problems. However, strong anti-corruption policies have “virtually extinguished” bribery and other forms of petty corruption in public services – an achievement that could serve as a model for other post-Communist countries. This article describes how this reduction in corruption has been achieved in the education system.

Causes and Forms of Academic Corruption – The Soviet Legacy

Unethical behavior is defined differently in different countries and cultures, and it is important to understand that political history is an important reason why corruption was so endemic in Georgia. Georgia was part of the Soviet Union for more than 70 years – a fact that shaped practices and norms that contributed to corruption. In the education sector, “cheating the system” was an acceptable social norm. The perception among the population, and for the most part the actual reality, was that the system was corrupt and unjust and that individuals had to do whatever necessary to prevail.

After the demise of the Soviet system, academic corruption flourished in Georgia. The over-centralized education system was dominated by former apparatchiks, and university rectors of some of the top universities soon acted as “Academic Barons” overseeing multi-million dollar corruption rackets. The embezzlement of funds dedicated to developing university infrastructure was commonplace, a fact that resulted in school facilities remaining in poor shape for years. The inflow of foreign aid and loans to improve education in Georgia also offered ample opportunities for graft.

The biggest money-making machine, however, was the university admissions process. Bribery in entrance examinations was rampant: by some estimates, more than half of available university seats were sold to students, whether they were qualified or not. The price of admission ranged anywhere from USD $200 to USD $10,000, depending on the university. At elite institutions like Tbilisi State University, it was virtually impossible to get admitted without hefty bribe payments, which could in some instances be as high as USD $30,000 – in a country where the average GDP per capita was only USD $8,838 in 2003 (World Bank). Bribery was so common that there was a running joke in Georgia “…about a man visiting a professor. “My son is such an idiot, he will never pass your entrance exams,” the man says, to which the professor replies: “I bet you $1,000 that he will!”1

After being admitted, it was possible for students to bypass the system and graduate by bribing university instructors. The price for examinations varied but could be in the hundreds of dollars. This type of corruption was enabled and institutionalized by very low pay for professors, which earned only between USD $20 and USD $50 a month in 2002. The willingness of teachers to resort to corruption is perhaps unsurprising under these circumstances – it is not easy to uphold ethical standards with an empty stomach.

Another problem was corruption in the accreditation of academic institutions following the privatization of education in Georgia. On one hand, privatization had some positive effects, as it allowed better-quality, foreign-sponsored institutions, such as the European School of Management and the Caucasus Business School, to enter the Georgian market. These institutions charged high tuition fees and were able to pay professors 30 times as much as public universities, a fact that contributed to better education. On the other hand, widespread bribery in the accreditation process led to a proliferation of low-quality private providers and diploma mills. In 2002 alone, 209 private institutions were licensed to operate in Georgia, many of them providers of dubious quality that only made it through the process via corruption.

Sadly, an entire generation of Georgian students went through their education under this corrupt system. Universities still produced capable graduates, of course, and students who wanted to study had opportunities to acquire knowledge. But success in higher education was often not based on merit, but on bribes and nepotism – a fact that advantaged richer segments of society. Endemic corruption also led to an overall deterioration of the quality and relevance of education: only 3 percent of graduates of Tbilisi State University, the country’s largest university, were reportedly able to find employment one year after graduation in the early 2000s. Georgia’s education system was in dire need of reform.

Education Reforms

Real change did not come until after the 2003 Rose Revolution when the government made education reforms a top priority. By that time, it was obvious that corruption was a major hindrance to the development of Georgia’s economy in general and its education system in particular. Georgia’s parliament had in 2002 approved a draft reform package for “Higher Education Development in Georgia.” Substantial reforms were not implemented until the beginning of 2004, when the new government, elected in January 2004, reshuffled Georgia’s university leadership, curtailed the influence of the powerful university rectors, and imposed far-reaching changes in university admissions and accreditation procedures that rooted out various forms of corruption.

Changes in University Admissions

A key element of the reforms was to take away admissions decisions from the universities in favor of a unified and centralized entrance examinations system. While universities had far-reaching autonomy in admissions decisions under the old system, university entrance is since 2005 determined in a much more transparent process without involvement of the universities.

Entrance examinations are now administered by a “National Examination Centre (NAEC),” which is a semi-autonomous institution under the purview of the Ministry of Education. The NAEC runs a number of testing centers throughout the country where applicants sit for written examinations, the results of which determine eligibility for admission. Test forms now have a barcode for personal identification, rather than the applicant’s name, which further reduces the potential for corruption. Initially, all NAEC examinations were graded by two independent evaluators with a third person acting as an arbitrator. But since 2011, the examination has been broken down into different components each double-blind-graded by two separate evaluators, which means that a total of at least six independent graders now assess each exam. The examinations can be freely observed by external observers and are monitored via closed-circuit cameras.2

New Accreditation Procedures

A new Higher Education Law in Georgia, approved in 2004, introduced new accreditation procedures that curbed corruption in the licensing of academic institutions and the spread of diploma mills. Another law on “Education Quality Enhancement,” adopted in 2010, further enhanced Georgia’s quality assurance mechanisms. The licensing and accreditation of academic institutions was changed to a more decentralized process overseen by a dedicated quality assurance agency detached from the Ministry of Education. Quality assurance was now under the purview of a new National Center for Educational Accreditation, and later, the National Centre for Educational Quality Enhancement (NCEQE), established in 2010. The corrupt academic elites were sidelined in this process. The council that is responsible for the authorization of institutions currently consists of nine members directly appointed and dismissed by the prime minister. Term limits are capped at one year, and members cannot be public officials.

The sweeping reforms increased transparency and made it virtually impossible for institutions to gain licensing solely through bribery. Compliance with quality standards was enforced with sanctions: enrollment quotas, for instance, were made contingent on positive accreditation outcomes. Financial transparency became part of the accreditation criteria, and several institutions were closed down for “failing to meet accreditation criteria largely because of insufficiency of resources or such corrupt practices as money laundering, misappropriation of university property and funds by academic or administrative staff.”

Other Reforms

Significant changes were also made in academic staffing to ensure that academic positions are being filled exclusively on the basis of open competition – the former practice of hiring relatives and friends is in the past. These changes were not easy to achieve: in 2005, for instance, all academic staff at Tbilisi State University were dismissed and had to reapply under a new selection process based on merit. The change also helped academic institutions to reduce their inflated numbers of professors and create better-paid positions, a fact lessening the incentive for corruption. While concrete statistics on professor salaries in Georgia are hard to come by, salaries are certainly better than ever before and stood at 1,150 to 3,550 Georgian lari (USD $360 to USD $1,300) for full-time professors in 2012/13. Overall, the removal of corrupt “academic barons” from academia has helped attract younger more qualified professors and administrators to universities.

Lasting Changes

With these far-reaching changes, the small country of Georgia achieved strong results in overcoming corruption and established a more transparent and better quality education system that can function as the bedrock of sustained democratization in Georgia. In conversations with this author, current government officials expressed confidence that the reform achievements are lasting and do offer Georgia a window of opportunity to take the country to the next level. Tamar Sanikidze, former Minister of Education and current head of the NCEQE, pointed out that there is strong “political will” in Georgia to continue with further education reforms. Current reform objectives include, for instance, greater autonomy for universities and the internationalization of accreditation procedures, a step that would further strengthen quality assurance. Georgia’s Prime Minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili announced in 2016 that he seeks to reform Georgian higher education using the German education system as a model.

Another official, Mariam Jashi, chair of the Parliamentary Committee on Education, Science and Culture even believes that improvements in higher education are such that Georgia can be made more attractive for international students and could become a hub for international education in the region. While still small, the number of international students in Georgia has indeed been growing substantially in recent years and increased almost tenfold between 2009 and 2015.3

1. Quoted from: Berglund, Christopher and Engvall, Johan: How Georgia Stamped Out Corruption on Campus, in Foreign Policy, September 3rd, 2015, https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/09/03/how-georgia-stamped-out-corruption-on-campus/

2. For an overview of the reforms see: Mariam Gabedava: Reforming the university admission system in Georgia, in: Transparency International: Global Corruption Report: Education. Routledge, pp.155-159.

3. The number of foreign degree-seeking students in Georgia increased from 499 in 2009 to 4,780 in 2015, as per the UNESCO Institute of Statistics. Most students currently come from neighboring Azerbaijan and India.