International Education in a Difficult and Uncertain U.S. Political Environment

Stephen C. Dunnett, Professor and Vice Provost for International Education, University at Buffalo – The State University of New York, and Amir Reza, Vice Provost, International & Multicultural Education – Babson College

On January 28, 2017 a presidential order suspended entry of all refugees to the United States for 120 days, barred Syrian refugees indefinitely, and blocked entry into the U.S. for 90 days for citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

The travel ban fiasco – and other actions out of Washington in the year and change since – have damaged U.S. higher education, and shaken the long held perception among students, their parents, and others of the United States as an open and welcoming country.

- In the last year, extreme vetting of visa applications for international students from many countries beyond the seven included in the first travel ban has become common.

- Threats to abandon or severely restrict optional practical training (OPT) opportunities for graduating international students, and threats to abolish or severely restrict the H-1b visa have also emerged.

- The administration has begun tightening the rules on new and renewals of H-1b visa applicants.

- It has also doubled down on the threat to build a wall on the border with Mexico, threatened to abolish the DACA program, and recently decided not to renew the temporary protected status of 60,000 Haitians and 200,000 San Salvadorans.

The litany of actions that have further increased uncertainty about U.S. openness and interest in engagement with the rest of the world goes on. Included are the decisions to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement, to abandon the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and to quit UNESCO, along with threats to tear up the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). It’s no stretch to say that U.S. friends and allies are deeply concerned about what appears to be an abdication of American historic world leadership and commitment to treaties and long standing U.S. policies.

This uncertainty has implications that cannot be ignored either on campus or off, especially by senior international education officers (SIOs) seeking to reassure international students, parents, and other stakeholders that institutions across the United States continue to welcome, support, and seek out the international students who bring cultural richness and intellectual diversity to academic endeavors, research, and campus life alike.

This article, written from the perspective of two senior administrators with long experience in the international sphere, seeks to put the events of the past year, and the actions that administrators and others can take, into perspective.

Immediate Triage: Fostering a Sense of Welcome

Babson College and the University at Buffalo are both active centers of international education. As SIOs on these two campuses, we have many years of experience in all aspects of international education: recruitment and enrollment of international students, international student services, study abroad, curriculum internationalization, international exchange, overseas programs, and international alumni engagement. We are both accustomed to the ever-changing geopolitical landscape around the globe. What we were unprepared for was facing such uncertainty in the U.S. with respect to immigration policies and procedures: The events of the last year caught us profoundly off guard.

The first proposed travel ban hit just over a year ago, just as many colleges and universities were beginning their spring academic terms. Continuing and new incoming students and scholars from the affected countries were stranded in their home countries, or in third countries as they were traveling to the U.S. SIO’s spent considerable time and effort trying to get their students and scholars back into the U.S., as well as assisting students who had been admitted with visas and yet denied boarding by airlines or entry at U.S. ports of entry.

colleges and universities were beginning their spring academic terms. Continuing and new incoming students and scholars from the affected countries were stranded in their home countries, or in third countries as they were traveling to the U.S. SIO’s spent considerable time and effort trying to get their students and scholars back into the U.S., as well as assisting students who had been admitted with visas and yet denied boarding by airlines or entry at U.S. ports of entry.

Amid uncertainty and external threat, SIOs confront a barrage of questions from our international and domestic students, our faculty and staff colleagues, our campus leaders, and from community stakeholders about all aspects of the international environment both on campus, in the country at large, and overseas.

- International students on campus seek reassurances about their immigration status, and their post-graduate employment opportunities.

- Domestic students and faculty seek assurances about how welcome and safe they will be studying or travelling abroad.

- Campus leaders and administrators are concerned about international enrollment issues and the inclusion and engagement of international students on the campus.

- Faculty is concerned about how to address the complex issues that arise in their classrooms in the current divisive political climate in the country.

These questions are complex and require data, analysis, and clear thinking – all of which require, in turn, significant time. Yet the speed of regulatory change, news flashes, and constant attention and scrutiny require quick action that leaves little time for thoughtful contemplation. Amid this chaos, it is still critical that we reassure students, visiting scholars and others about the current events of the time.

In response, Babson College and the University at Buffalo, like other institutions throughout the country, have sought to convey the message that our campuses are open and welcoming to international students, scholars and visitors from around the world. In particular, we have stressed that our campus communities have been enriched by the presence of international students and scholars who have made invaluable and far-reaching contributions to our research, education and engagement missions. We have stressed that international students and scholars on our campuses enhance diversity and contribute to the cultural and intellectual life of our communities. These messages seek to reassure not only international students and scholars already on our campuses, but also prospective students and families overseas.

We have also focused on identifying and executing other remedies. These include:

- Pragmatic supports for students already on campus

- Advocacy off campus

- Addressing the impact of exorbitant costs that may deter enrollments among international students who now have many high quality, lower cost options for study outside the United States

Pragmatic Supports: How Babson and the University of Buffalo Have Responded

One answer is that institutions must double down on pragmatic supports for students already on campus. We must make our campuses more hospitable in real ways that matter, so international students will have a positive and rewarding academic and social experience, and carry that memory – which will last well beyond the term of any presidential administration or academic career – back home.

SIOs must lead the charge. We must engage our faculty and administrator colleagues as allies in our efforts. We must champion quality experiences for international and domestic students. We must act as trusted advisors to campus senior leaders on internationalization strategies.

What does this look like? At Babson College, we have made significant investments to create an ecosystem which integrates international students into all facets of the campus environment. International students are an integral part of the institutional mission to educate entrepreneurial leaders, and the college takes pride in being a welcoming and nurturing campus for international students. This is accomplished not only through the efforts of the international office; faculty and staff work together to engage in efforts to recruit, educate, and engage international students in and out of the classroom. These efforts are evident in our pedagogical approaches from orientation to career development, and alumni engagement. For instance, Student Affairs professionals and student leaders organizing orientation for all students integrate international and domestic students into one program with the goal to maximize interactions. In addition, this year a new series was launched focused on race and racism in the U.S. designed to equip international students with language and concepts to engage with peers/classmates when critical incidents arise and to highlight behaviors/language that cause microaggressions and further the divide especially between international and students of color. Mangers of student leadership positions intentionally collaborate with the international office to solicit nominations from the international student body for these student leadership positions. These efforts create a diverse cohort of student leaders who engage with one another across nationalities and set examples for future generations of students. Yet another example is the presence of staff in the career who specialize in advising international students.

At the University at Buffalo we have been able to maintain international enrollment by continuously improving international student services, such as academic advisement, ESL and international student orientation programs, while developing a strong campus-wide program of international student inclusion and engagement. For example, international students are invited to participate in a mentoring program led by U.S. faculty, staff and student volunteers, as well as English conversation groups and a rich variety of extra-curricular activities designed to bring international and domestic students together, on and off campus. Recently the provost appointed a campus wide task force on the inclusion and engagement of international students which recommended inclusion, engagement and integration of international students on the campus must be a primary part of the university ethos. The task force made 51 recommendations to improve the integration of international students which are currently being implemented.

Advocacy and Awareness: Make the Case to Politicians and Regulators

In our recruitment travels over the last year, we have seen a troubling trend: Prospective international students frequently ask us if our government welcomes them to study in the United States. This apprehension about studying in the U.S. has significant economic ramifications well beyond campus borders. An Institute of International Education survey found the number of new international students enrolling in many campuses across the country declined on average 7 percent for fall 2017, and there is widespread fear the drop will be even greater in fall 2018. Historically, the U.S. has been the top destination in the world for international students. As a leading host country for international students and scholars, the U.S. has benefited significantly from the presence of large numbers of international students on our campuses.

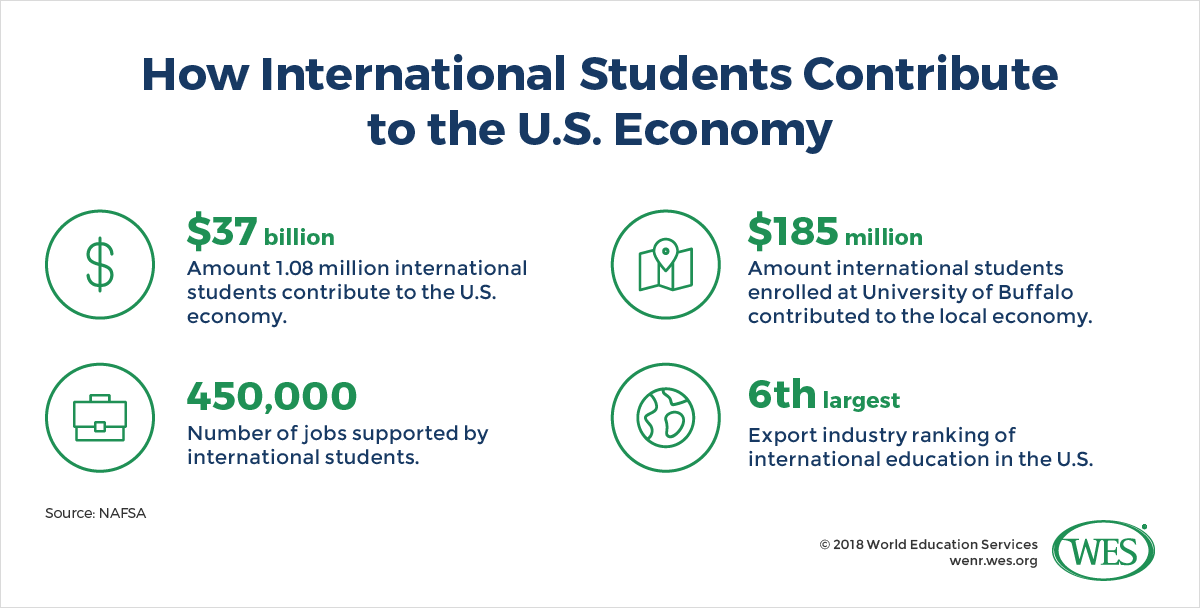

In 2016 the 1.08 million international students studying in the U.S. contributed approximately $37 billion to the nation’s economy and supported 450,000 jobs according to NAFSA: Association of International Educators. This makes international education the sixth largest U.S. export industry.

A decline in the number of international students would have a major economic impact not only on American universities and colleges, but also to the U. S. economy. For example, NAFSA reports that international students enrolled at Babson College contributed over $65 million to the greater Boston area, and international students enrolled at the University at Buffalo contributed $185 million to the economy of Western New York.

Our overseas competitors in the global student market have been quick to exploit prospective students’ uncertainty about study in the United States. This competition, although accelerating in the new climate, is nothing new. In fact, although the raw numbers of international students in the U.S. has grown consistently for years, the percentage of students coming to the U.S. vis-à-vis its competitors has been steadily decreasing since 2001. Other countries have long been the beneficiaries of U.S. loss in the world education market. The stakes have ramped up in the past year, with Canada, Australia, Europe, and China each significantly increasing their share of global enrollments.

In this environment, SIOs (and U.S. higher education associations) must make the economic case for internationalization at all levels of government, advocating for its benefits at the city, state, and federal level as the opportunities arise. This case must be clear and supported by relevant data. The goal is appropriate government regulations that help to foster a welcoming environment, and a sense of certainty and stability, for international students.

Addressing the Price Gap: Beyond Traditional Sending Markets and Middle-Class Recruits

In the past, families of international students perceived the high cost of a U.S. higher education as a sound investment in their children’s future. However, just as uncertainty drives away investment in business, the uncertainty of the U.S. regulatory environment, the perceptions of xenophobia, and lack of opportunities for employment authorization post-degree-completion is causing some families to consider alternatives elsewhere.

Even prior to the new uncertainties, the ever increasing cost of a U.S. higher education has begun to drive the U.S. out of some international markets. This has caused our institutions of higher education to become increasingly over-reliant on a few source countries, namely China, India, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, and Canada. These are all countries with rising middle classes able and willing to pay the high cost of a U.S. higher education; however even they are starting to falter as costs increase and currency exchange rates become less favorable.

If the U.S. is to remain competitive, its institutions of higher education must contain or even reduce costs, increase value, and try to diversify their source countries. In some cases this means providing scholarships to students from developing countries. In other cases, it means identifying promising new markets, and taking a disciplined, long-term approach to building a recruitment pipeline. It may also mean redesigning recruitment strategies in consistently strong markets, for instance, targeting less penetrated locales in India or China. Above all, it means – as discussed above – creating holistic support systems that address the unique and varied needs of students who do enroll, and effectively supporting them throughout their tenures on campus.

Looking Ahead

We do not wish to generalize from our experiences as international education leaders, and certainly our two institutions have experienced and responded to the impact of the events of the last year differently. However, we believe that our concerns are broadly shared. Internationalization has taken place at many U.S. institutions of higher education over the past two decades, and the evidence indicates that American universities and colleges across the nation have been affected by – and continue to be concerned about –changes in U.S. policies and procedures on immigration, and shifting perceptions of U.S. openness at home and abroad.

But we also believe that, in these times of uncertainty and change, there is cause for hope. Competent, knowledgeable, and passionate leaders have it within their power to continue the efforts of internationalization, to ensure and explain the benefits to our campuses and society at large, and to educate new cohorts of international students who can carry home the message that the United States is an open and welcoming country. A country that does not wall off its neighbors and does not disparage immigrants or countries less fortunate than our own. Our hope is that, a few years hence, we will all emerge with a clearer sense of how important the mission of international higher education is, both in terms of developing global competence in our domestic students and in enriching our institutions of higher education by welcoming students and immigrants from overseas irrespective of religion, race or country of origin, as the United States has done for more than a century. This is what has and will continue to encourage international education exchange to benefit societies in the U.S. and abroad.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).