The European Higher Education Area (EHEA): Has It Lost Its Way?

By Hans de Wit, Director of the Center for International Higher Education, Boston College, and Fiona Hunter, Associate Director of the Centre for Higher Education Internationalisation at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy

Introduction

Across Europe in the 1990’s, national governments struggled to fully realize necessary higher education reforms. Banding together to address this difficulty, the ministers of education in France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom signed the Sorbonne Declaration in Paris in 1998. The declaration called for greater harmonization in order to modernize European higher education systems.

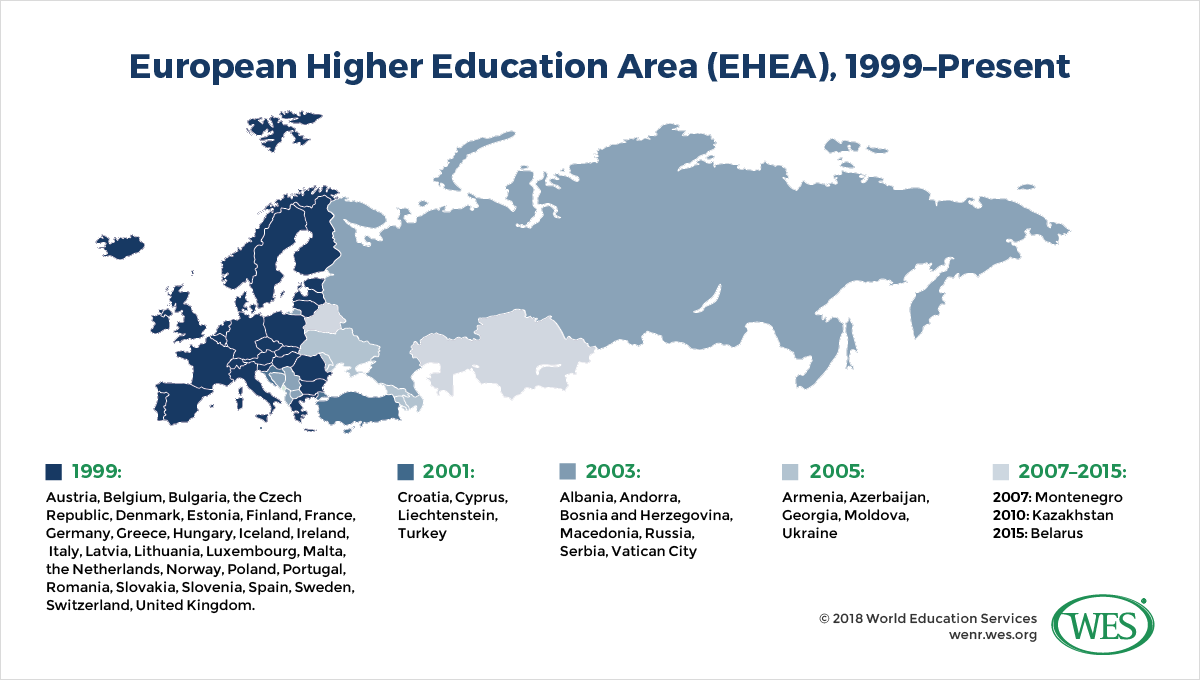

A year later, seeing opportunity in a European effort, the ministers of education of 29 countries signed the Bologna Declaration with a view to constructing the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). For the first time in history, European countries of different political, cultural, and academic traditions agreed upon a number of common objectives that would enable national higher education reforms within a broader European context.

The aim was to ensure that European higher education institutions (HEIs) would be able to enhance cooperation through the exchange of students and staff and the development of joint programs with trust and confidence, thanks to greater transparency and a common frame of reference.

The EHEA also meant that students and graduates in Europe would have greater mobility and enjoy “full recognition of their qualifications and periods of study,” and also have greater access to the broader European labor market. As a result, higher education in the European region would increase its international competitiveness and become more attractive to other world regions. This competitiveness would, in turn, enhance opportunities for greater cooperation with higher education systems in other world regions.

The Bologna Process led to the creation of a number of remarkable tools to meet these aims. It developed a common qualifications framework; the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), a common credit system; common principles for the development of student-centered learning; common standards and guidelines for quality assurance; a common register of quality assurance agencies; and a common approach to recognition.

While originally set to end in 2000, the Bologna Process still operates, meeting regularly and proposing new higher education reforms. The number of signature countries has expanded from the original 29 to the current 48. Moreover, the process has inspired other regions in the world—such as the member countries of the Association of South East Asian Nations, as well as regions in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East—to explore how similar models of convergence might be introduced in their own higher education systems. The Bologna Process has not only become an expression of successful intra-regional cooperation and mobility within Europe, it has become a model for greater intra-regional cooperation and mobility in other world regions.

Historical Foundations

What is the European story behind the success of the Bologna Process, and can this success continue? Many argue that universities have always had some international dimension, either in the concept of universal knowledge or in the movement of students and scholars. People who hold this view refer back to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, when, in addition to religious pilgrims, university students and professors were a familiar sight on the roads of Europe as they traveled in search of communities of learning.

While limited and scattered in comparison to the modern EHEA, there was a kind of medieval “European space” defined by a common religion, a shared language (Latin), and a set of academic practices. The resemblance may only be superficial, but we can still see similarities in the promotion of mobility, common qualification structures, and the gradual growth of English as the common academic language today.

However, it must be pointed out that the much-loved historical references to the university as an essentially international institution ignore the fact that most European universities originated in the 18th and 19th centuries with a distinct national orientation and function. In many cases, there was a process of de-Europeanization. Mobility was rarely encouraged—it was even prohibited—and Latin as the universal language of instruction gave way to national languages. It wouldn’t be until after the Second World War and the creation of the European Community that Europeanization would be back on the higher education agenda.

The European Community strengthened as a unitary economic and political power between 1950 and 1970, but it was not until the second half of the 1980’s that European programs for education and research emerged. The Erasmus program for exchange students within the European Union grew out of smaller initiatives that had been introduced in Germany and Sweden in the 1970’s, and a European pilot program from the early 1980’s. It was later grouped together with similar initiatives in the 1990’s under the umbrella program Socrates. It has evolved more recently into Erasmus+, an even broader program that embraces education, sports, and youth programs.

It wasn’t until the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992 that Erasmus and other programs began to be based on any educational rationale and roles of the European Community. Rather, these programs were originally developed out of a need for greater competitiveness in relation to the United States and Japan, and the desire to nurture a sense of European citizenship and identity. The program activities have always been based primarily on cooperation through student and staff exchanges, joint curriculum development, and joint research projects, and the enthusiastic institutional response to these programs set a clear path for the European approach to internationalization.

The Erasmus program in particular has meant that European institutions continue to attach great importance to cooperation and mobility. However, beyond the three million mobile students who have studied or worked abroad because of Erasmus grants, the program has had an even greater impact on the internationalization and reforms of higher education. It piloted ECTS and initiated access to membership in the European Union for countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and other aspiring candidates. Through such actions, it paved the way for the Bologna Process and the realization of the EHEA.

Although much has been accomplished, many challenges remain, partly as a result of the growing number of countries that have different traditions and systems that joined in later years, but also because the original impetus of the 10-year process ending in 2010 has been lost. At one level, harmonization has taken place, but at another, the process is leading to greater diversification among the different systems.

What Will the Future Bring?

Critics of the Bologna Process see it as part of a neo-liberal, market-oriented approach to higher education. And although that characterization may be an oversimplification, the focus on making European universities competitive at a global level was an important dimension of the reform.

While the increasing focus on economic rationales has not changed in recent years, it has now collided with the more nationalist-populist trends in the global and European political climate. Brexit, the refugee crisis, the emerging trade war, and the related growth of nationalist movements and governments, as well as anti-global, anti-international, and anti-European sentiments in countries such as Hungary, Italy, Poland, and others are challenging the increased focus in higher education on internationalization and Europeanization—the key drivers of the Bologna Process.

Can we consider the decisions taken at the 2018 Bologna Process Ministerial Conference in Paris as a response to these negative trends? Although there were no strong statements or decisions for action made during the meeting, the references to academic freedom and anti-corruption in higher education illustrate the rising concern in the higher education community and among ministers of education in the face of the current trends. Furthermore, the support—although with some reluctance from certain countries, such as the Netherlands—for the plans of the French president to create European university networks, can be considered one attempt to counter these developments.

The same can be said of the significant proposed increase in funding for the Erasmus+ budget by the European Commission, from the current €14.7 billion to €30 billion for 2021–2027 with the aim and ambition of strengthening European identity.

In other words, there are both positive and negative signs with respect to the future of the European landscape of higher education and its internationalization. Much will depend on how countries and institutions respond to both the challenges and opportunities they face, how they envision their own future, and how strong their beliefs in a European identity and commitment to a shared European project continue to be.

The future that lies ahead for Europe and its higher education systems is one of uncertainty. The issues have become bigger, the climate more tense, and a less cooperative spirit can now be discerned. The European dream is being seriously challenged by many who seek to offer a different way forward. The answer lies not so much in confuting these alternative visions, but in offering a bigger and better one. Can European universities rise to the challenge?

Hans de Wit is director of the Center for International Higher Education, Boston College, United States. He is also chair of the board of directors of World Education Services (WES). Email: dewitj@bc.edu.

Fiona Hunter is associate director of the Centre for Higher Education Internationalisation at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy. Email: fionajanehunter@gmail.com. This article builds partly on their article, “The European Landscape: A Shifting Perspective,” in Internationalization of Higher Education – Development in the European Higher Education Area and Worldwide, DUZ, Germany, forthcoming.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).