Digital Academic Records: A Credential Evaluator’s Perspective

Dragana Borenovic Dilas, Documentation Specialists Team Lead, WES

Over much of the past decade, the number of academic documents shared electronically increased at a steady but only moderate rate. However, over the past year or so, their numbers have skyrocketed.1 With the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting access to campuses and postal services, digital documents have often been the only way that institutions, learners, and others could transmit academic records.

To credential evaluators and others on the receiving end, the influx of electronic documents, while offering a welcome alternative to broken transmission routes, can feel overwhelming. Recipients and credential evaluators in particular must now become familiar with a multitude of online platforms, document portals, and digital technologies that are used to verify and share documents electronically. Evaluators need to understand a bewildering tangle of technical terms and digital processes. By revolutionizing the way documents are sent, received, and authenticated, digitization has transformed the credential evaluation workflow itself.

Long before the start of the pandemic, World Education Services (WES) had begun to expand its use of electronic documents. More recently we have worked with a growing number of electronic credential formats, document delivery methods, and relevant digital technologies, all of which have provided us with invaluable insight into their practical applications, potential pitfalls, and future trajectory. With digital credentials likely to play an increasingly important role in the transmission of academic records and the mobility of global learners, the need to understand the basics of digital credentials will be indispensable to credential evaluators of today and beyond.

Document Content and File Format

There are many types of digital credentials; each contains a unique mix of academic information and is packaged in a distinct file format. But they all share features that cannot be replicated on paper-based documents.2 These include advanced digital security protections, such as encryption and cryptographic algorithms, electronic transmission channels, and, of course, their digital file format.

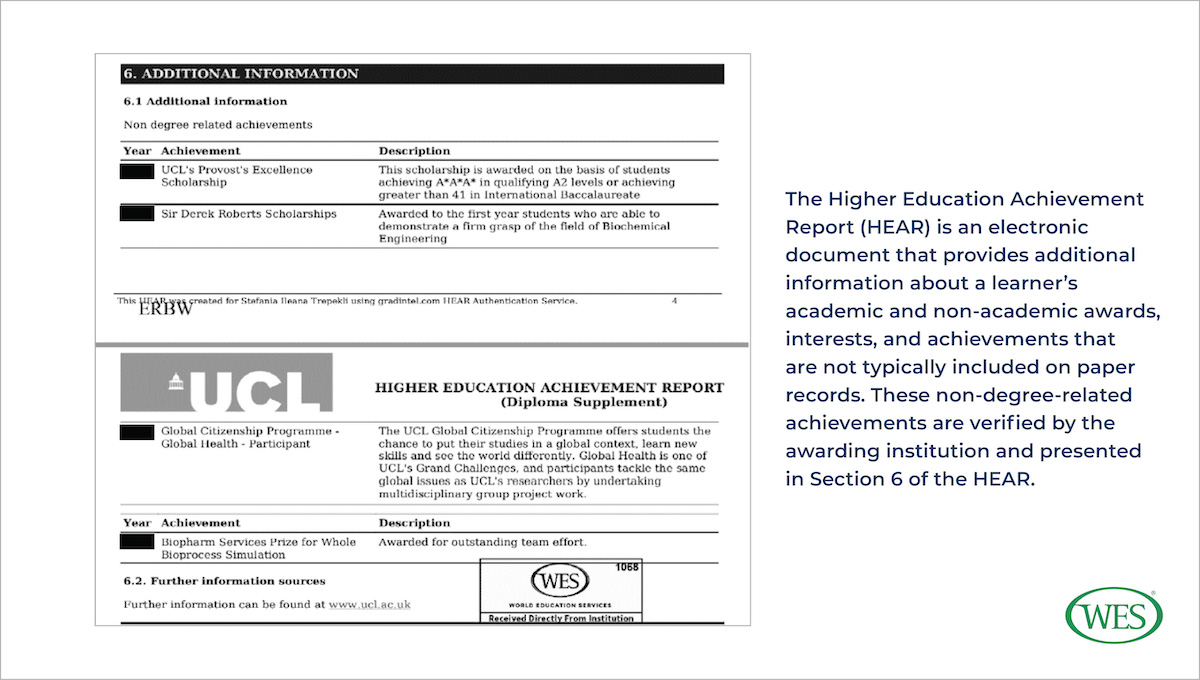

One of the most promising aspects of the digital format is its potential to store a far more comprehensive record of a student’s achievements than is feasible with paper documents. While most digital credentials contain the same information found in traditional paper records, a growing number include more. For example, in addition to providing information about a student’s course of study, grades, and degree classification, the Higher Education Achievement Report (HEAR), an electronic document issued by universities across the United Kingdom, also contains information about a student’s non-academic awards and interests. Institutions in other countries have piloted similarly comprehensive digital credentials. In the United States, some institutions are trialing the Comprehensive Learner Record (CLR), while 18 countries in the European Union are testing out the Europass Digital Credential. In Australia too, accredited institutions issue Australian Higher Education Graduation Statements (AHEGSs).

According to their proponents, these information-rich credentials do more than provide educational institutions and employers with a broader perspective on a learner’s experiences, skills, and competencies. By acknowledging non-academic accomplishments, they encourage learners to pursue interests outside the classroom. For credential evaluators, comprehensive digital records can provide fast and convenient access to information about academic programs, education systems, and learners’ activities and achievements not captured by traditional transcripts.

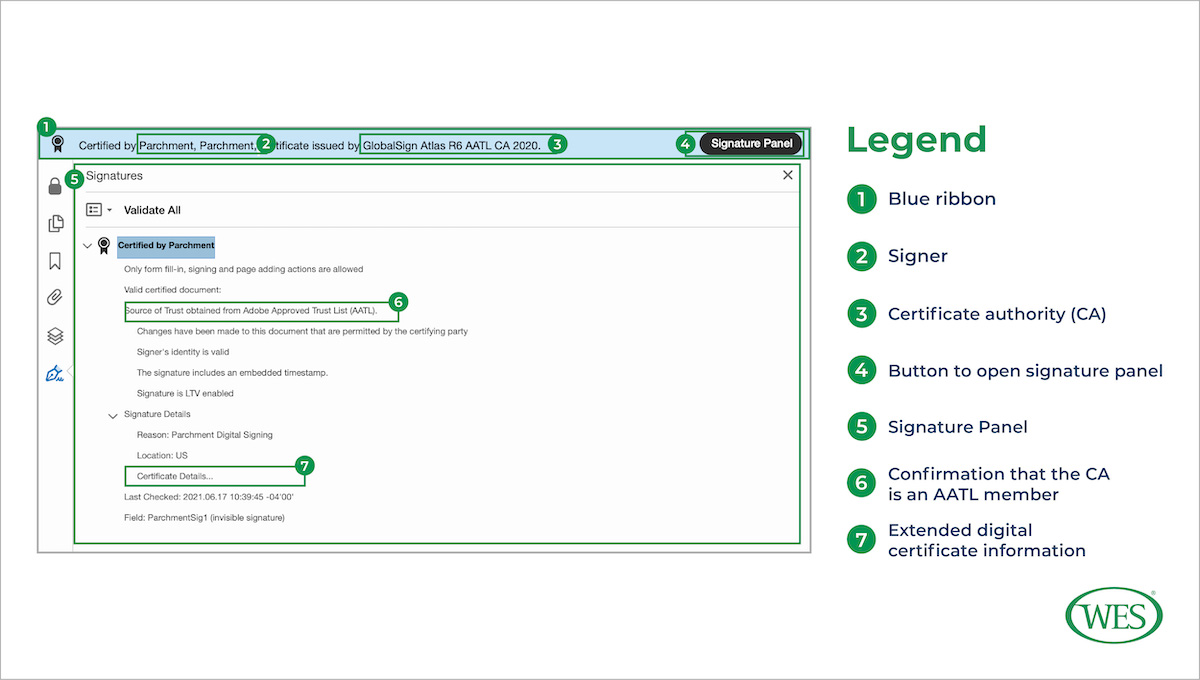

Regardless of the breadth of information contained in them, most digital credentials are encoded and shared as portable document format (pdf) files. To ensure that pdf files are secure and tamperproof, institutions often protect them with a digital signature, an advanced electronic signature that uses cryptography to verify the identity of the signer and ensure that transmitted documents have not been altered. In the U.S. and many other countries around the world, electronic signatures have “the same legal status as handwritten signatures.”

To digitally sign documents, colleges and universities typically work with an organization (such as Gradintelligence, My eQuals, and the National Student Clearinghouse, among others) that has been issued a digital ID by a trusted third-party certificate authority (CA) listed on the Adobe Approved Trust List (AATL). CAs on the AATL are all first vetted by Adobe Inc., the company that developed pdfs, to ensure that the third parties “meet the assurance levels imposed by the AATL technical requirements.”

When a pdf file is opened in Adobe Reader or Adobe Acrobat, digital signature information appears in a blue ribbon at the top of the document. For example, valid, certified documents shared by learners through the online platform Parchment will display the following ribbon when opened:

Clicking on the blue ribbon will open an expanded signature panel which displays additional information evaluators can use to instantly verify the authenticity of the document received. If the document is valid, the signature panel will confirm that the identity of the signer (in this case, Parchment) was verified by a CA listed on the AATL (GlobalSign), and that the content of the document was not altered after it was signed.

Not all institutions protect pdf files with digital signatures. Some opt instead to password protect or encrypt academic credentials that are sent as pdfs. Password protected pdfs require the recipient to enter the correct password to open the document. Encryption, a feature available in Adobe Acrobat Pro or through third-party service providers, provides stronger document security than password protection, hiding a document’s contents by encoding them in a form unreadable to humans or computers. Encrypted pdfs can then only be decrypted and opened with a password.

When securing digital credentials through either encryption or password protection, the issuing institution typically assigns a unique password to each recipient. It then shares that password in a separate email, not in the message containing the document. Providing the password separate from the document ensures that anyone intercepting one message or the other will not be able to open the document.

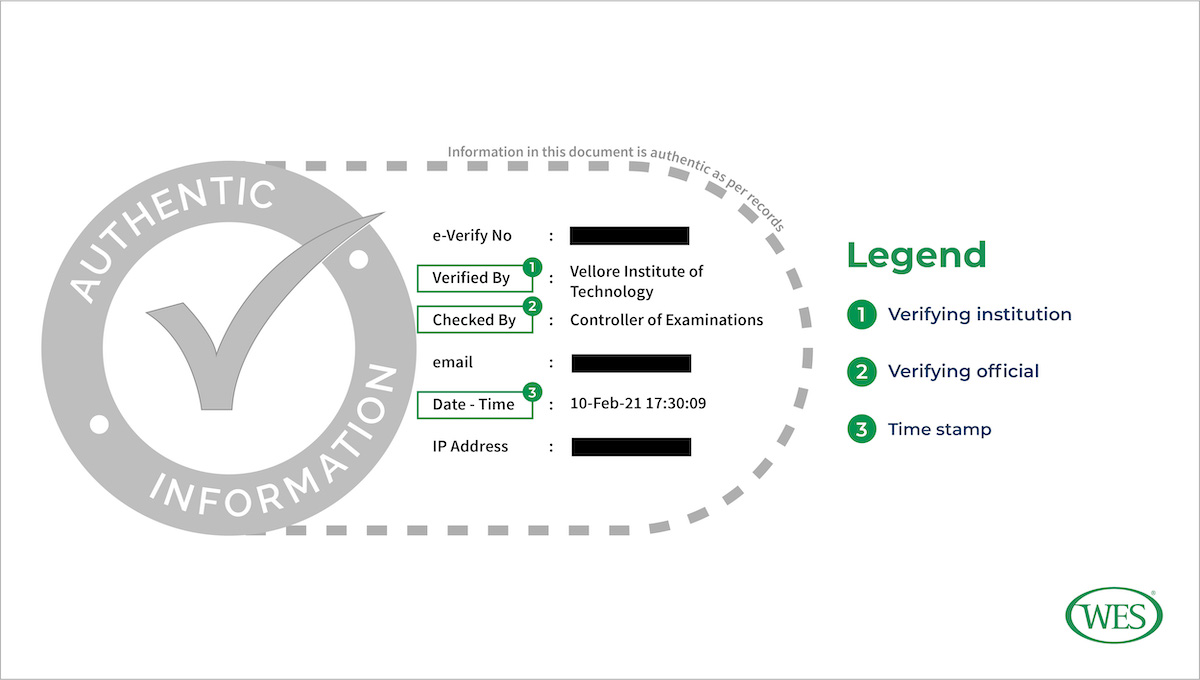

In addition to digital signatures, password-protection, and encryption, a feature unique to electronic credentials is the digital stamp or seal. These are not just scanned images of the stamps that institutions often use to authenticate paper documents, although such seals are not uncommon on digital credentials. Instead, digital stamps and seals function in a manner similar to digital signatures—they verify the origin and integrity of transmitted documents. For example, DocsWallet, an online platform used by many Indian institutions to share educational credentials electronically, includes the following digital stamp on verified documents:

As can be seen in the example seal above, these seals typically contain important information that can be used to validate the authenticity of the document to which they are digitally sealed. They often include the name of the verifying institution (usually the same as the awarding institution), the name or position of the person who verified the document, and the date and time when the document was verified, or the time stamp. The time stamp registers when a digital document was verified and shared with the learner or other recipient and can help credential evaluators archive and manage the digital records they receive.

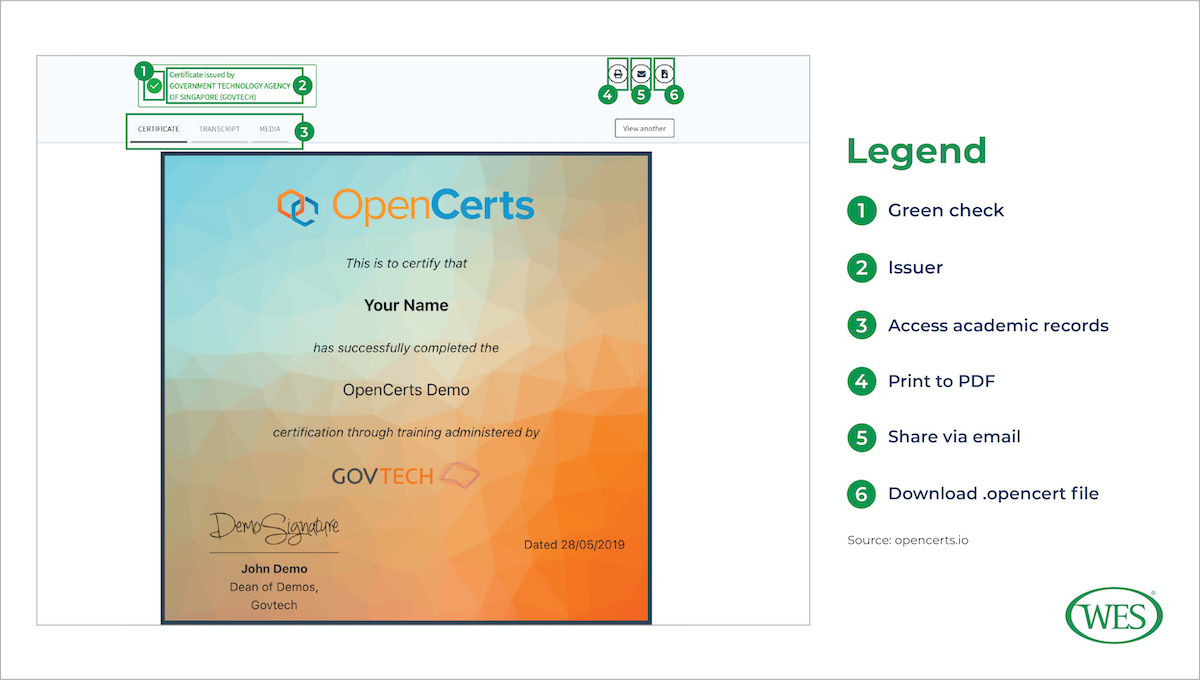

Besides pdf files, some institutions—most notably those in Singapore and the United Arab Emirates—issue blockchain-based digital credentials, often known as blockchain verifiable credentials. Institutions have been using blockchain technology to issue and verify educational credentials since 2017. Blockchain verifiable credentials offer a number of benefits to students and institutions. They grant learners a greater degree of control over and ownership of their credentials; they enable instant, cryptographic verification; and they provide state-of-the-art document security.

One popular blockchain-based platform is OpenCerts, which is built on the Ethereum blockchain and is currently used by 18 educational institutions in Singapore. For learners, as well as for sending and receiving institutions, the platform provides a simple and reliable way to verify and download academic transcripts and degree certificates. To ensure that electronic records are tamperproof, the platform uses cutting-edge cryptography. First, it encrypts academic documents as an .opencert file; then, it generates from that file a cryptographic hash value which it publishes on the Ethereum blockchain. Each hash value is unique to the .opencert file; even small alterations to the file will produce very different hash values.

This process provides both a high level of privacy protection and tamperproofing. If opened outside of the platform, the .opencert file will just display long, unreadable lines of code. However, when uploaded to the OpenCerts portal, the platform automatically generates a hash value from the file and compares it with the data stored on the blockchain. If the hash generated from the file matches the data on the Ethereum ledger, the platform decrypts the .opencerts file and renders a readable version of the academic document. Because data published on the blockchain cannot be altered, blockchain technology guarantees that the document opened by the recipient is the same as that issued by the institution.

According to their advocates, blockchain verifiable credentials promise to transform the transfer and recognition of academic credentials. By decentralizing the verification process, they give learners full ownership of and control over their academic documents. Unlike pdf files, which in most cases must be shared directly by the issuing institution or an authorized third-party digital document provider to ensure authenticity, OpenCerts documents can be shared directly by learners. Since these documents can only be verified through the OpenCerts portal, the way in which these files are transmitted from the issuer to the recipient has no bearing on their authenticity.

Blockchain technology may also simplify the work processes of sending and receiving institutions. The cryptography of blockchain technology makes it impossible to alter documents after they have been issued, freeing awarding institutions and credential evaluators from the often lengthy process of verifying paper-based documents.

But with the new technology also come new challenges, especially for credential evaluators. Traditionally, when credential evaluators receive digital academic records, such as pdf files, via email, they must first vet the sending address to make sure that the source is authorized by the awarding institution to issue academic documents, such as the Office of the Registrar or the Controller of Examinations. Because there are only a limited number of sources at each institution that are authorized to issue documents, this verification process can be quickly scaled, with documents from approved, already verified email addresses accepted and separated from those not yet vetted.

However, as OpenCerts documents illustrate, new technologies make it possible for authentic documents to be shared from unofficial sources. While blockchain verifiable credentials eliminate the need for evaluators to verify a source’s identity, they require recipients to more thoroughly vet all documents received from unofficial or personal email addresses. Evaluators will need to investigate an increasing variety of electronic documents sent from personal email addresses to see if the documents’ authenticity can be established even though they were not shared from an official source. Evaluators can no longer treat all documents received from non-institutional sources the same.

Document Delivery

Digital credentials have not only changed the content and format of academic credentials, they have also transformed document delivery methods. In general, there are three principal channels through which credential evaluators receive electronic documents: direct transmission, online platforms, and email.

Direct Transmission. Direct transmission channels automatically transfer documents into a recipient’s database. Recipients can partner with awarding institutions or third-party providers to receive electronic documents through either secure file transfer protocol (SFTP) or application programming interface (API). SFTP is a secure and automated way of transferring files between the sender and the recipient. SFTP encrypts commands and data, protecting sensitive data and user login credentials from being intercepted by third parties. API is also a mode of automated document transmission which ensures that data are encrypted and unmodified. As APIs require sending and receiving institutions to establish and maintain necessary digital technology, they are often not as easy to implement as SFTPs. Direct channels of transmission between the recipient and sender offer a number of benefits over other delivery methods. They not only minimize the risk of credential fraud, they also decrease the manpower required to access and download documents. They can also help strengthen relationships between sending and receiving institutions.

Online Platforms. Online platforms, which are document depositories hosted by universities or authorized third-party providers, are another trusted means of transmitting digital credentials. They also grant learners a high degree of control over their academic credentials. After creating an account on an online platform, learners have lifetime access to their educational credentials which they can then share anytime with anyone.

The process of transferring documents from online platforms to recipients, unlike with direct transmission channels, is not automated. Learners and recipients each have a part to play in initiating and concluding the transfer. Although the process varies by awarding institution and online platform, learners typically initiate the process by creating an account, often called a digital wallet, on the platform used by the institution they attended. The institution uses the platform to store some or all of its academic records. Learners can then use the platform to share their documents with whomsoever they desire. After the learner selects a recipient, the platform or the university automatically sends an email with a document access link to the recipient. Once credential evaluators receive the email with the document access link, they log in to the platform with their own login credentials to download or print the document.

Since this process is not automated, there are a few issues that can delay the evaluation of documents shared via online platforms. Evaluators will need to thoroughly research new platforms to ensure that they are secure and trusted sources. After verifying the platform, evaluators will need to create an account, understand the platform’s document-sharing options, and investigate whether and how documents can be downloaded, saved, printed, and verified. When evaluators encounter a new platform, this process can take some time.

Confusion on the learner’s end can also delay evaluations. Learners may accidentally restrict document access to the account holder (themselves), inadvertently requiring recipients to use the learner’s personal username and password to view the credentials. By using a learner’s username and password to log in to the platform, credential evaluators can gain unwarranted access to the learner’s personal information, a clear violation of most data protection and privacy regulations. In these cases, evaluators will need to request that learners select the appropriate document access settings and reshare their documents.

Learners may also download their academic records from the platform and send them as email attachments from their personal email addresses. In this case, credential evaluators would need to treat the received documents as unverified, and request that the learners resend their credentials through the platform’s established channels. Only documents shared directly by the university or through a third-party platform are guaranteed to have been verified by the issuing institution or by an authorized third-party platform and not to have been altered.

Email. Today, online platforms and direct transmission channels are the safest, most secure methods of sharing documents electronically. They are also among the most expensive: Institutions must pay to subscribe to online platforms or to develop and maintain their own. Some choose instead to send documents via email. For evaluators, ensuring the authenticity of documents received via email can be challenging. Without a digital signature or password, the contents of academic credentials sent as pdf files can easily be altered, as can the sender’s email address. Email spoofing, which manipulates an email message so that it displays a false sender address, can make it appear that forged academic documents were sent from an official source.

Despite these hurdles, institutions can take a number of steps to ensure that documents received over email are secure and authentic. These include:

- Establishing stringent anti-spoofing authenticity controls and security checks for all incoming emails, and training evaluators in how to detect spoofed email addresses. Often the easiest way to do this is to invest in one of the many anti-spoofing security options offered by email management or computer security companies.

- Thoroughly verifying the email addresses from which documents are received by checking the institution’s website or its official publications, such as university brochures and handbooks, or by directly contacting previously verified institutional authorities. Recipients also need to confirm that the sender is authorized by the awarding institution to issue and send academic records. While the authorized sender often varies by country and institution, some common examples include the Office of the Registrar; the Controller of Examinations; the Exams, Awards and Graduation Department; the Department of Student Services; and the Office of Academic Records.

- Scrutinizing documents closely for any discrepancies in content or layout. If any discrepancies are noted, these documents should be returned to the issuing institution for verification.

- Advising institutions to encrypt or password protect attached pdf files if they are unable to use digital signatures. Academic institutions must pay to obtain a digital ID or to use the services of a company that has a digital ID.

- Encouraging institutions to use direct digital delivery options whenever possible. Credential evaluators should consider promoting the benefits of these options to issuing institutions. For example, sending documents via SFTP is as easy as sending documents via email. However, SFTP offers far more transparency and security.

Document Authentication and Verification

The process of authenticating digital credentials aims to answer the same two questions as the process of authenticating paper-based credentials: Were the documents sent directly from the issuing institution? And, if they were, were they handled, and potentially altered, by anyone other than an authorized person at the institution that issued them?

As the discussion above reveals, digital credentials can provide conclusive answers to those questions, provided credential evaluators take the necessary precautions. To ensure that digital documents are received directly from the issuing institution, credential evaluators will need to research and validate each source, whether digital platform or institutional email address, before initiating the document exchange. This process will likely require close contact and coordination with awarding institutions and may involve multiple email exchanges, phone calls, and virtual meetings with different staff members before a new source can be approved and cleared for use.

Evaluators will also need to work to ensure that the mode of transmission used is secure and tamperproof. Establishing direct digital transmission channels can take time and effort, but once they are set up it is nearly impossible for third parties to intercept and alter transmitted documents. Digital portals may require extensive training and disruptive adjustments to evaluation procedures, but their use of cryptography, electronic signatures, and multifactor authentication provides a high level of document protection. Even emails, which are among the least secure of all transmission methods, can be safeguarded by rigorous vetting practices and protocols that define how data should be exchanged.

But once digital credentials are integrated into the credential evaluation workflow, they can greatly accelerate authentication and verification processes. To verify the contents of a paper document, credential evaluators need to send a copy of the document by mail or email to the awarding institution, which then checks the document received against its records and sends a response. This process can take anywhere from a few days to a few months. While the way in which digital documents are verified varies according to their format and the method by which they were shared, in many cases verification can be done instantaneously.

How does the instant verification of electronic transcripts work? One of the most common examples is the verification that is inbuilt within digitally signed pdf files, as explained above. For some documents that are not digitally signed, online portals and platforms can enable evaluators to verify their authenticity by either comparing the received document with the copy available in the online database (for example, University College Dublin, Universidad de la República in Uruguay, and Lovely Professional University in India) or uploading the files for document verification (New Zealand Record of Achievement Document Verification and Singapore Management University).

Instant verification does more than reduce the likelihood of fraud. It also accelerates the credential evaluation process, and, ultimately, has a positive impact on learner mobility. Spared a potentially lengthy credential verification process, learners can transition more smoothly from one academic institution to another, or from university to employment or life in another country.

Digitization and the Future of Credential Evaluation

Electronic documents are transforming the credential evaluation workflow, prompting evaluators to continually adjust, develop, and reconsider their existing processes. Given that electronic academic records expedite the credential evaluation process, it seems likely that they will be used more widely over time. Two developments in particular are likely to have a significant impact on the digitization of academic documents and the future of credential evaluation: a growing recognition of the importance of learner agency, and a drive to increase the automation of credential evaluation processes.

A growing number of institutions are beginning to recognize “learner agency” as a key principle of equitable teaching and educational administrative practices. With respect to academic records, the ideal of learner agency calls for institutions to transfer control over how, when, and with whom academic documents are shared to the students themselves. Transferring credential ownership to learners expands their ability to act on their own initiative, allowing them to use their verified, hard-earned credentials as they see fit. Given this growing awareness, it seems likely that issuing institutions and third-party platforms will develop new learner-focused digital credentials, and that credential evaluators will increasingly receive digital credentials shared directly from learners’ email addresses or their personal digital wallets.

While the direct, digital transmission of documents has automated the initial phase of the credential evaluation workflow (receiving the documents), there is still room for digitization to streamline later phases of the process. Currently a large percentage of documents—both those received on paper and those received via email or online platforms—require manual processing. Even digitally signed pdfs, which do much to accelerate processing times and reduce opportunities for fraud, must still be manually downloaded from an online platform or an email attachment and uploaded into the database by credential evaluators. Evaluators then still need to enter relevant credential information from the pdf file—such as the institution attended, the qualification received, and the grades earned—in their database.

But that could change as well. Sharing structured, machine-readable data promises to enhance interoperability, or the ability of different computer systems or networks to work together to exchange and make use of data. Instead of storing images of academic records, issuing institutions often already collect and organize information from transcripts or degrees in electronic databases as structured data. Working together, or partnering with third-party providers, sending and receiving institutions could exchange this structured data directly, allowing it to be more easily read and organized by the receiving institution’s computer system. A credential evaluator would not have to, for example, manually enter the names of all the courses, but instead this data would automatically be transferred from the issuing institution’s database.

Developments in that direction already appear to be gaining momentum. A 2020 white paper published by Nuffic, the Dutch organization for internationalization in education, explored the topic in depth. Titled Digital Student Data and Recognition, the paper categorized digital document formats by their data maturity level, or their level of machine readability and potential for automation; it ranked pdf files—the most common digital credential format—with the lowest digital data maturity level. But it also highlighted the potential that sharing and receiving digital student data with higher maturity levels, such as structured data, has to further digitize and expedite the credential evaluation process.

Europass Digital Credentials Infrastructure, for instance, uses Extensible Markup Language (XML), which is both a human- and machine-readable data format. XML facilitates the direct exchange of credential information from the issuer’s to the recipient’s electronic database. Sharing structured data will not only save time, money, and the computer storage space needed to store the files, it will also reduce transcription errors as evaluators will no longer be required to enter data manually. With digital credentials becoming more prevalent, it is likely that evaluators will be confronted with a growing variety of digital file formats containing unstructured and, increasingly, structured data.

The changes within the credential evaluation workflow brought about by the digitization of academic records have the potential to enable faster, more accurate, and more equitable evaluation processing. Understanding the basic principles and future trajectory of digital credentials can help credential evaluators leverage these new technologies and facilitate, for learners, greater and more cohesive access to further study, job opportunities, or life in another country.

1. Although the use of digital documents has grown rapidly in recent years, their history extends decades into the past. In 1998, more than 30 years ago, the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO) established the Standardization of Postsecondary Education Electronic Data Exchange (SPEEDE) committee, which is active in “developing and promoting the implementation of standards for electronic exchange of student education data.” More recent initiatives include the Groningen Declaration Network which, by “bringing together stakeholders in the digital student data ecosystem,” has been a major driver of the digitization and portability of student data since it was established in 2012.

2. A considerable proportion of academic credentials transmitted electronically are simply scanned images of paper credentials. As these credentials differ little from printed photocopies of paper credentials and lack many of the security protections of digital documents, such as encrypted data, they are not discussed in this article.