Decline and Recovery in Challenging Times

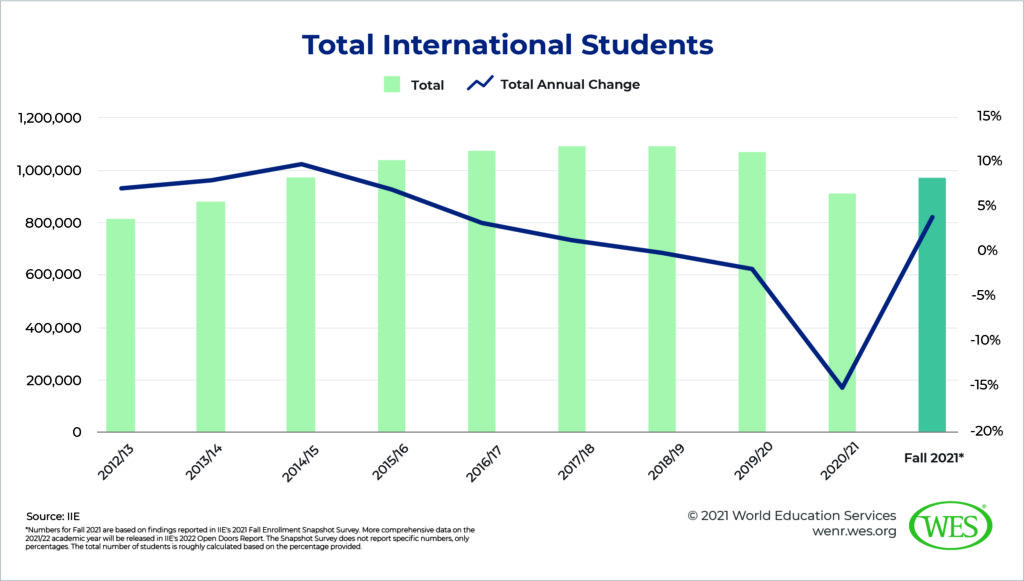

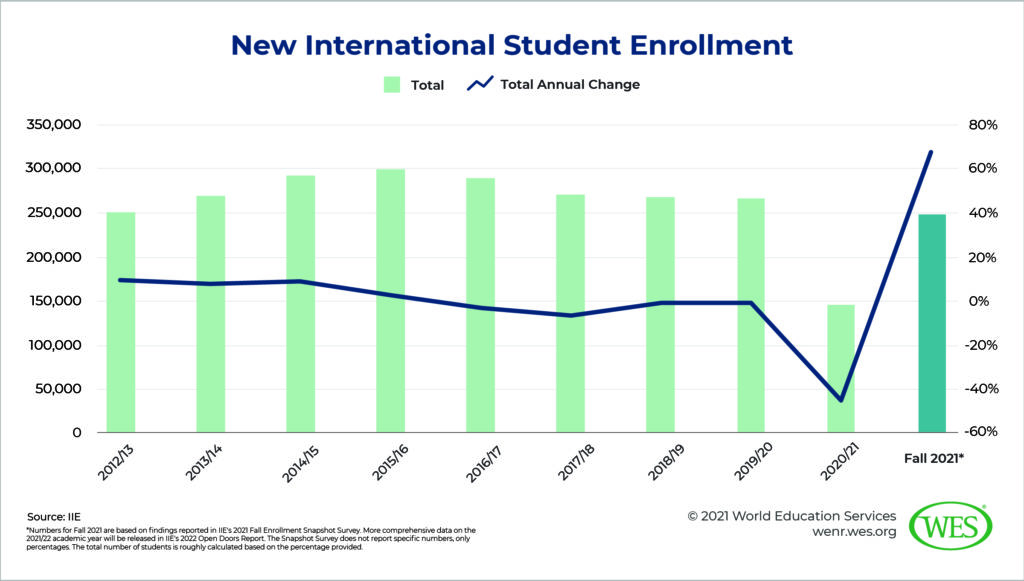

The recently released 2021 Open Doors Report on International Education Exchange (Open Doors, for short) from the Institute of International Education (IIE) revealed the toll that the COVID-19 pandemic took on international student enrollment in the United States. It prompted a staggering 15 percent decline in international students in the 2020/21 academic year, the first full academic year impacted by the pandemic. However, there is good news for the 2021/22 academic year, courtesy of IIE’s annual Fall Enrollment Snapshot Survey: International enrollment began to rebound this fall. The total number of international students in fall 2021 increased by 4 percent, and new student enrollment grew by an astounding 68 percent.

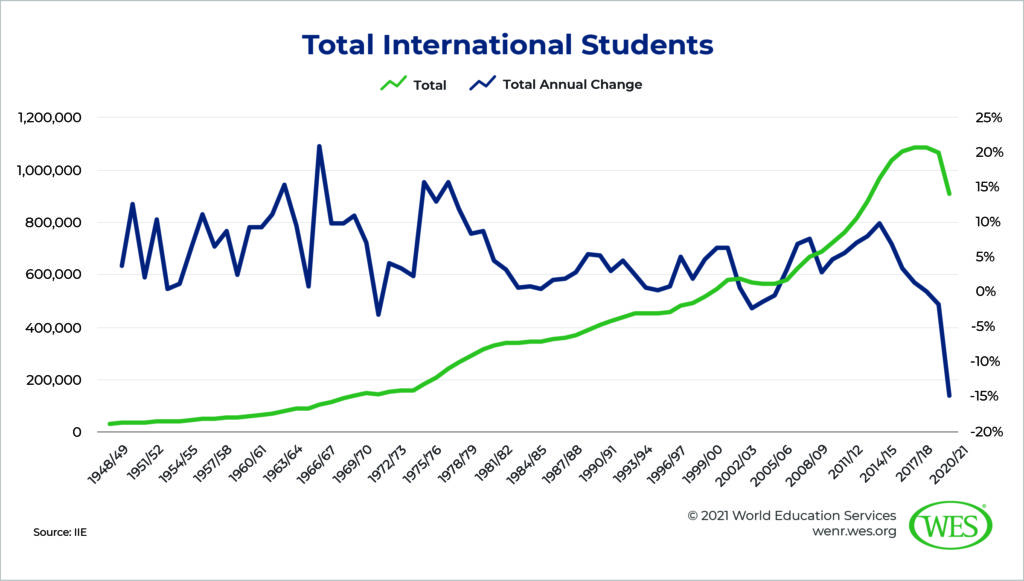

These numbers clearly illustrate the unprecedented challenges brought on by the pandemic. They also signal the start of a recovery, sparked by the widespread distribution of vaccines and the loosening of virus restrictions. While the pandemic dominates the story now, other factors also impact the flows of students into the U.S., some of which have been in play for much longer. It is important to view these new numbers not just against the background of the pandemic and the budding recovery but also within the context of these longer-term trends.

A Tumultuous Year and a Half

The number of international students in the U.S. dropped from over one million in 2019/20 to 914,095 in 2020/21, according to the latest Open Doors report. This is the steepest year-over-year decline, by a significant margin, since IIE began tracking data in 1948. Even more staggering: New student enrollment declined 45.6 percent, from 267,712 the previous year to 145,528.

Naturally, most of this huge decline can be attributed to the health crisis. COVID-19 was first declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020, and massive disruptions to all aspects of life worldwide, including to higher education and travel, began around the same time. Yet, the 2020/21 academic year was the first full year impacted by the pandemic. From last March until November 8 of this year—when the Biden Administration lifted travel restrictions on international travelers vaccinated against COVID-19—nationals of many countries were banned from entering the U.S. These banned countries included major international student source countries, such as Brazil, China, India, Iran, and the United Kingdom, as well as the entire Schengen Area of Europe. Additionally, in July 2020, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) announced that it would not allow international students enrolled exclusively in online courses to travel to or remain in the U.S. for the fall semester. This resulted in many students in countries like China and India attending online classes in the middle of the night due to time zone differences. And a large number of students—about 40,000, according to the 2020 Fall Enrollment Snapshot Survey—deferred enrollment to a future semester or year.

In addition to the pandemic, 2020 and early 2021 were eventful for other reasons, notably when it comes to the socio-political environment. There were the Black Lives Matter protests that began in June 2020 following the high-profile brutal killings of George Floyd and other Black Americans. At the same time, there were protests, at times armed, against many of the pandemic restrictions imposed by various state and local governments across the country. Then came the rancorous 2020 presidential election and, on January 6, 2021, the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, an unprecedented breach of one of the main symbols of American democracy. While the extent of the impact of specific events and movements on international students is hard to determine, WES research suggests that the overall socio-political environment has an impact on international student decision-making. Forty percent of prospective international students surveyed in August 2020 said that they were less interested in studying in the U.S. because of this environment, an increase of 5 percent from June.

The good news is that it appears that international enrollment made at least a partial recovery this fall. In the U.S. and many other countries around the world, COVID-19 vaccines are readily available (although vaccine inequity, particularly between wealthier and poorer countries, remains a major concern). And restrictions designed to slow the spread of the virus have been gradually relaxed across the U.S. Furthermore, the Biden Administration introduced a National Interest Exemption for students from countries impacted by pandemic-related travel bans, which went into effect in August 2021, allowing more students to travel. According to the Fall Snapshot Survey, almost all institutions (about 99 percent) have resumed at least some in-person classes, with hybrid models (a mixture of in-person and online) being the predominant modes of instruction.

The Fall Snapshot Survey shows that total international student enrollment is up about 4 percent, showing a slight but not full recovery from the 15 percent decline in 2020/21. More hopefully, new enrollment has shot up 68 percent, indicating a strong recovery. Still, questions remain about when and whether a full recovery will occur. This will, in large part, depend on the remaining course of the pandemic. The very recent emergence of the Omicron variant throws more uncertainty into the picture, raising the possibility that more lockdowns and travel bans will be introduced.

The Longer View

The COVID-19 pandemic has been front of mind for a seemingly long time now, but there are significant questions about longer-term trends. It’s impossible to predict the future. But there are clues to what the future (as the pandemic eventually comes to an end) may portend in the broader context, when stepping back and viewing not just through the lens of the pandemic.

For one, international student enrollment in the U.S. was slowing and beginning to decline even before COVID-19 arrived. Per Open Doors data, enrollment peaked in 2018/19 at 1,095,299 before declining slightly in 2019/20, the year preceding the outbreak of the pandemic. The growth rate, however, had begun to slow several years before. The annual growth rate itself peaked most recently in 2014/15, at 10 percent. (Higher growth rates had not been seen since the 1970s.)

This slowdown mirrors an earlier decline in new international student enrollment. Since peaking at over 300,000 students in 2015/16—the last full academic year under the Obama Administration—first-time international student enrollment has declined steadily. While the number of continuing students buoyed overall enrollment for a few years more, this steady decrease in new students finally led to overall declines in 2019/20. And last year, in 2020/21, for the first time since the immediate post-September 11th era, the number of students on OPT (Optional Practical Training) declined, the final effect of the decrease in new student enrollment that began about five years ago. It is, however, likely that many OPT-eligible students chose to return home due to the pandemic, causing a more dramatic decrease than would have been seen otherwise.

These declines in new and total international student enrollment coincide with the years of the Trump Administration. While the impact of the policies and rhetoric of that administration is difficult to ascertain exactly, they undoubtedly played a role in these declines.

Trends Among Top Sending Countries

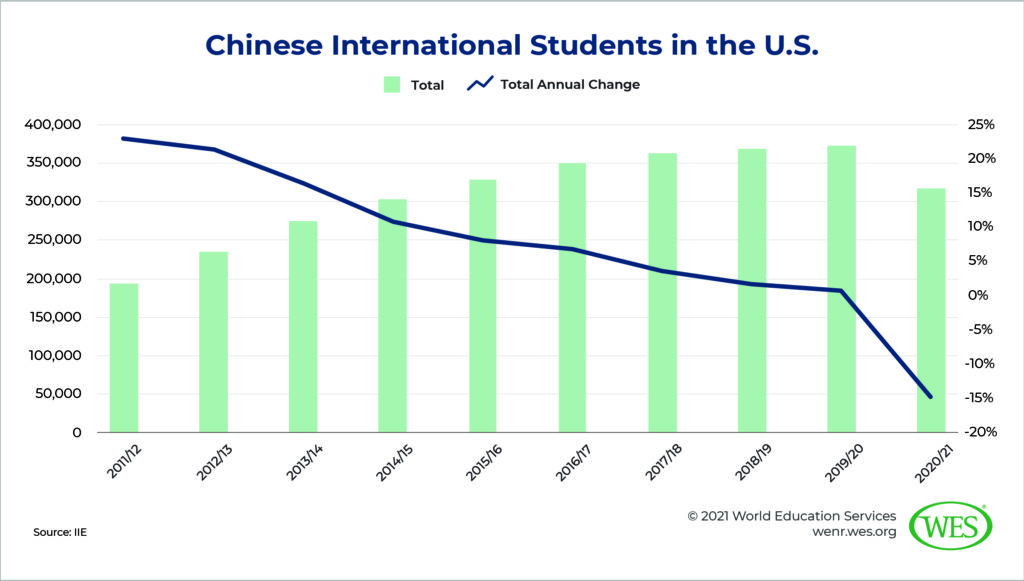

U.S. policies and politics are likely front and center for many international students. At the same time, external and more systemic factors have also heavily shaped international student flows. These factors have impacted various sending countries and regions differently. Perhaps the best example of the interplay between U.S. policies and longer-term external trends—recently complicated by the pandemic—involves Chinese international students. In 2020/21, Chinese enrollment decreased by nearly 15 percent, somewhat on par with other major sending countries. However, even before that, Chinese enrollment growth had begun to slow precipitously. After years of phenomenal expansion starting in the mid-2000s, enrollment growth had slowed to less than 1 percent by 2019/20.

Certain Trump Administration policies, several of which the Biden Administration has continued, may have discouraged some Chinese students from coming to the U.S. In 2018, the Trump Administration reduced the duration of student visas for Chinese graduate students in certain fields from five years to one. Additionally, on a number of occasions, the Trump Administration accused some Chinese students of espionage and barred those believed to have ties with the Chinese military from coming to the U.S. Once the pandemic became a full crisis in the U.S., President Trump frequently blamed China for the outbreak, referring to the coronavirus as the “China virus,” a term deemed xenophobic by many. And Chinese nationals were among those banned from entering the U.S. early in the pandemic. All of this led to a sense of unease among many Chinese students who were already in the U.S.

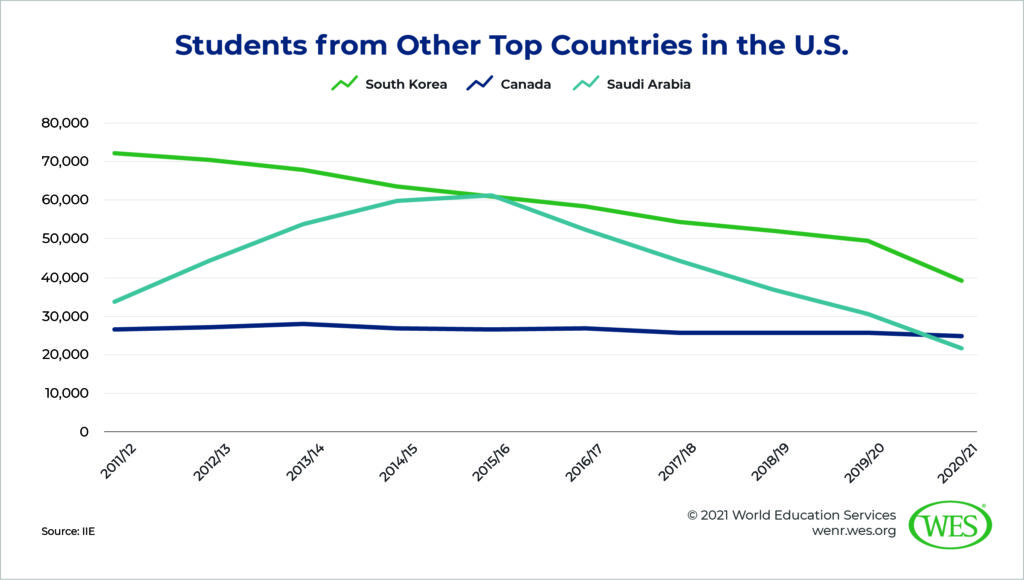

In addition to political developments in the U.S., factors within China itself have also likely driven the enrollment slowdown. The country has dramatically improved access and quality within its own higher education sector. Furthermore, many Chinese students who have returned from studying overseas have faced employment challenges, with their U.S. degree no longer giving them an advantage on the Chinese job market. These factors have likely influenced the decisions of many prospective Chinese international students on whether to go abroad (and, if so, where) or stay home. A similar phenomenon in South Korea is widely recognized as a factor behind the long, slow decline of international students from that country enrolled in the U.S.

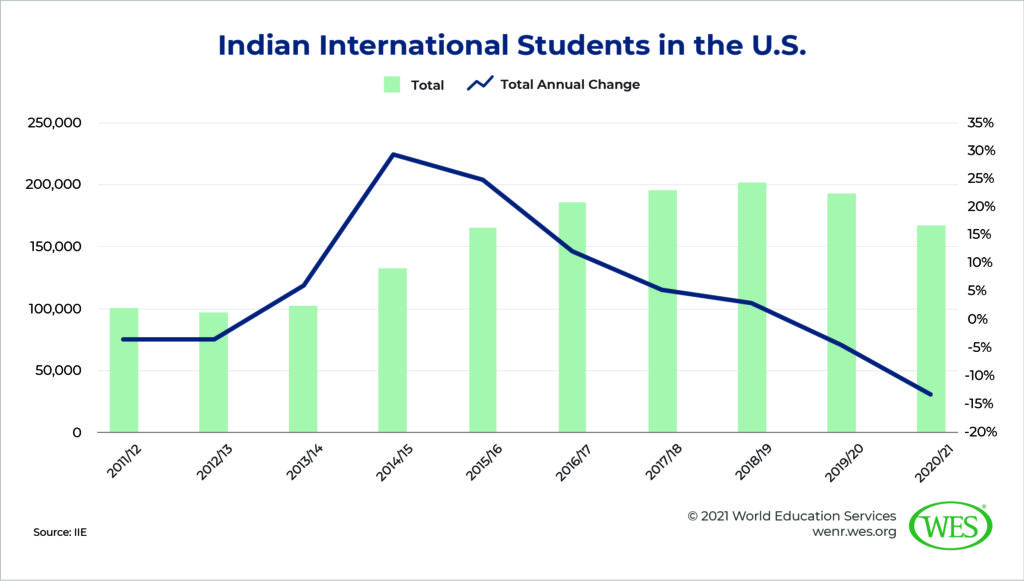

Indian students, the second largest group, witnessed phenomenal, double-digit growth from 2013/14 to 2016/17, before slowing significantly and eventually declining in 2019/20, a year before the start of the pandemic. In 2019/20, enrollment declined by 4.4 percent, and it decreased by 13.2 percent in 2020/21. In particular, Indian students have been attracted to the U.S. by the opportunity to work and potentially gain permanent residency. Indian nationals hold, by far, the largest number of H-1B visas. Evidence suggests that the Trump Administration’s moves to scale back OPT and the H-1B visa programs may have dampened the enthusiasm of Indian students to study in the U.S. At the same time, other countries have become more attractive for Indian students because of their more generous work and immigration policies. Canada, in particular, has seen impressive gains in Indian students (pandemic aside), likely due to its immigration policies, which allow international students to work after completing their studies and open pathways to permanent residency.

In this year’s Open Doors report, the top five sending countries remained the same as in recent years, although Saudi Arabia dropped to fifth place behind Canada. Over the past several years, there has been a steady and fairly swift decline in the number of Saudi students enrolled in the U.S. This decline is largely due to major changes in the King Abdullah Scholarship Program (KASP), the principal driver of the phenomenal growth of Saudi students in the U.S. that started in the mid-2000s. (The recent fate of KASP and Brazil’s now defunct Science Without Borders scholarship program, which drove a huge expansion in the number of Brazilian international students for several years, shows the volatility of such large-scale, government-funded scholarship programs and their susceptibility to both political and economic pressures.)

Canada, by contrast, tends to remain relatively steady as a sending country to the U.S., with slight increases some years and slight decreases others. This year, Canadian international student numbers declined by only 3.3 percent, the least of any top sending country. Geographic proximity, strong economic and cultural integration, and the ease of travel between the two countries certainly play a role in this stability. That said, there has been a slight decline in the number of Canadian students in the U.S. from a high of almost 30,000 in 2008/09.

Looking Forward

There is no doubt that the pandemic is the leading factor shaping international student mobility in the U.S. and elsewhere today. With large numbers of people worldwide still unvaccinated and new variants of the virus continuing to emerge, it is unlikely that the health crisis will fully subside anytime soon. But, eventually, it will come to an end. When it does, other factors—within the U.S., in sending countries, and in other competitive host countries—will again assume a major role in shaping student mobility flows. Given their current and future importance, these other factors should not be overlooked.

While some of these trends were worrisome prior to the pandemic, the fate of international higher education in the U.S. is far from sealed. The U.S. is still the top destination for international students worldwide by a significant margin and will likely continue to be so for a long time. Academic institutions—as well as the federal and state governments—should continue to highlight the value and openness of the U.S. higher education system to international students from around the world.