India’s Moment: An Examination of Student Mobility from and to a Key Player

Indian students are exploring educational opportunities worldwide, with growing interest in both traditional and emerging study destinations.

With about 1.3 million students abroad, India is the second-largest sending country after only China. Outbound student mobility from India has grown tremendously in recent years, particularly benefiting the so-called “Big Four” destinations, all predominantly Anglophone: Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. But Indian students are increasingly studying around the world, and many countries and institutions have taken notice of this dynamic group of talented young people. As an example, India is now the top country of focus for recruitment at both the undergraduate and graduate levels among U.S. institutions, according to the Institute of International Education’s (IIE) 2024 Snapshot on International Student Enrollment, or Fall 2024 Snapshot, for short.

This article examines the current state of global student mobility in regard to India. I examine first why so many students leave the country for educational opportunities abroad. Then, I look at outbound Indian mobility trends, with a particular focus on recent major changes in the Big Four. Lastly, I look at India as a possible educational destination in its own right and how the Indian government is shaping such efforts.

The Context: Why So Many Indian Students Go Abroad

Enrollment in India’s higher education system has increased substantially in the last few decades. In 1995, the gross enrollment ratio for tertiary education in India was only 6 percent. In 2023, it was 33 percent, according to data from the World Bank. India recently overtook the U.S. to become the second-largest higher education system after China. This has been the natural outgrowth in gains at the primary and secondary school levels. Gross enrollment at the secondary school level went from 46 percent in 1995 to 79 percent in 2023, a reflection of major investment from the Indian government. The growth in higher education has also paralleled strong economic growth. The GDP per capita has gone from US$375.2 in 1995 to US$2,480.8 in 2023. Greater income among more Indians means that many families can more readily afford to send their children to a university or college.

Of course, higher education growth ultimately reflects demographics. India’s total population has grown about 50 percent since the mid-1990s to about 1.4 billion, recently surpassing China to become the most populous country in the world. There is an enormous youth dividend. But two major challenges, in particular, prompt many of India’s most talented students to go abroad: lack of seats in quality institutions and programs and problems securing gainful employment after graduation.

Lack of seats in quality programs

One major challenge is that India’s higher education system has not been able to keep pace with enrollment growth, particularly at the graduate level. While solid data on available spots in Indian institutions relative to demand are lacking, most experts agree that the issue is as much about accessing quality programs as sheer number of seats. As a result, many Indian students with at least some means look to go abroad.

As the sector has massified in recent decades, the quality of new institutions and programs has not kept pace. A 2023 World Bank report sums up the challenges: “Despite its size and growth rate, and the emphasis placed on tertiary education by Indian policymakers in recent times, the system has faced continuous challenges of equitable access, quality, governance, and financing, with the quality of inputs and outputs not keeping pace with the expansion of the sector.” Additionally, as public institutions have lagged behind the growth in enrollment, private institutions have stepped in. Most of these private institutions “are of poor quality and have marginal reputations,” according to Philip Altbach, though a few high-quality nonprofit universities have entered the field.

The problem appears to be particularly acute at the graduate level, as large numbers of students at this level, mostly master’s degree students, seek education elsewhere. Data on Indian students in the U.S. bear this out. Nearly 60 percent were studying at that level in 2023/24. Proportionally, more Indians in the U.S. are studying at the graduate level compared with other major sending countries. This trend has held constant for years. The U.K. records a similar breakdown, as does Australia.

Seats in India’s top institutions are extraordinarily competitive. The original five campuses of the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), considered to be among India’s best universities, are said to have lower acceptance rates than the Ivy League universities. One research study on the IITs provides a good example: “At the undergraduate level, admissions to the IIT system are determined solely based on student performance on the annual Joint Entrance Examination (JEE), a centrally administered exam covering mathematics, chemistry, and physics. The competition is fierce; in 2010, for instance, around 450,000 individuals took the JEE, competing for less than 10,000 IIT places.”

The Indian government has largely recognized the issues of quality within the higher education system and proposed numerous changes via its National Education Policy (NEP) released in 2020. These include ending the “fragmentation” of universities across the country, allowing for more autonomy among both institutions and faculty, revamping curricula, creating a National Research Foundation to boost research and peer-review journal article output, and instituting a “light but tight” regulatory framework under a single regulator. Improvements to the system will take time and significantly more government funding, and in the meantime, many Indian students will choose to attend high-quality institutions abroad.

Problems with Post-Graduation Employability

Equally problematic for students and their families, and for India as a whole, are the employment prospects for graduates. According to a briefing from the Ministry of Labour and Employment, the unemployment rate among higher education graduates stood at around 13.4 percent in 2022-23. By contrast, the rate in the U.S. is around 2.3 percent, and in Canada, it’s about 4.2 percent, in 2023. The International Labour Organization finds the rate in India to be even higher, around 30 percent, according to reporting by The Business Standard. The article further notes that “higher educated young people are more likely to be unemployed than those without any schooling.” Relevant job creation has simply not kept pace with the number of young Indians entering the labor market.

In tandem, there have long been concerns about the employability of the graduates of Indian higher education programs. Much of the reporting on this discusses poor alignment between higher education and the job market. In the recently released India Skills Report 2025, created by a consortium led by Wheebox, an Indian testing company now owned by ETS (Educational Testing Service), only about 55 percent of Indian graduates were deemed employable, though this percentage is an all-time high in the 12-year history of the report. (The report presents an analysis of two datasets: one is a test given to Indian graduates to determine their employability, and the other, a survey of over 1,000 Indian companies related to hiring.) Employability, however, varies by field and credential. MBA holders and those with degrees in computer science and information technology are more employable than those in various engineering fields, according to the report.

These problems with employability originate in the quality concerns found throughout the higher education sector. As N.V. Varghese notes, “The poor quality of higher education results in declining employer confidence in the competencies of graduates.” For example, soft skills – such as collaboration, critical thinking, and ethics – are increasingly deemed very important by Indian employers, but these skills are often not a major part of curricula at many institutions. As a result, many Indian students seek opportunities abroad not only to learn but to gain work experience that will make them more employable. Many use the opportunity to attempt to immigrate permanently.1

The Destinations: Where Indians Choose to Go

The top destinations continue to be the Big Four predominantly Anglophone countries: Canada, the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom, in that order according to the latest available data. Together, they capture at least three-quarters of the total Indian student population abroad.2 Well-reputed higher education institutions, highly developed economies, the English language, post-study work opportunities, and strong Indian migration ties with these four countries will likely continue to drive this trend. However, all four countries have faced recent signs of current or impending decline in the number of Indian students, even after robust post-pandemic growth. The cost of study, visa delays and denials, changes in policies toward international students in terms of both study and work opportunities, changes in the opportunity to stay on longer term, and safety issues all likely play important roles, and to a large extent, all have appeared in all four countries.

Enrollment Trends in the Big Four

Over the last half-decade, the top destination for Indian students has been Canada, passing the U.S. as top host in 2018/19. In recent years, the growth has been phenomenal. In 2023, Indians accounted for more than 40 percent of all study permit holders in the country, at 427,085 students, according to data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). Canada’s success has largely been driven by generous policies for international students, particularly in regard to the opportunity to work after graduation through the post-graduation work permit and opportunities to transition to permanent residence. Compared especially to the U.S., Canada had until recently been seen as a safe, welcoming, and relatively affordable destination. Full data for 2024 have yet to be released, as of this writing, but because of new restrictive policies (among other factors, discussed below), Canada has likely faced a decline of 45 percent in study permit approvals in 2024, based on an analysis by ApplyBoard. The analysis confirms that Indian study permit approvals likely fell noticeably.

Until the 2018/19 academic year, the U.S. had been the top destination for Indian students for many years. Despite losing that distinction, the U.S. has experienced significant growth from India in recent years. In 2023/24, India surpassed China to become the top sending country of international students after more than a decade, according to the Institute of International Education (IIE). (India was previously the top country of origin throughout the first decade of the century.) That year was also an all-time high: 331,602 Indian students. However, this appears to be the peak. For fall 2024, U.S. government data from the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) showed a drop of about 24 percent in Indian enrollment, along with drops in overall international student enrollment.3

Australia is currently the likely third top destination. In 2023/24, there were 163,450 Indian students in the country, according to the Australian Department of Education. Australia has long been a popular destination for Indians. However, it took much longer for the international education sector there to rebound after the COVID-19 pandemic compared with those of other top destinations. This was driven mostly by Australia’s particularly strict pandemic policies, which barred international students and even some Australian citizens who were outside of the country from returning. As a result, the country took a reputational hit, according to many commentators. It took Indians in particular a while to return in pre-pandemic numbers, but that changed in 2023. However, like Canada, Australia has recently introduced limits on international students that will certainly mean a decline in Indian student enrollment.

There is a bit of a lag in data from the U.K., but in 2022/23, there were 126,580 Indian students in the country, according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). Despite the U.K. being likely in fourth place, there has been almost a four-fold increase in Indian students in the country since 2018/19. In fact, compared with the other three countries, the U.K. rode out the COVID-19 pandemic better, with no significant drops in the number of Indians or international students in general, due to more relaxed policies. That said, reporting from The Times of India notes that Indian applications to the U.K. declined by about 20 percent in fall 2024, per Home Office data.

What do globally mobile Indian students study?

There are few concrete international datasets on the level and fields of study of Indian students. However, there are data from some countries from which we can extrapolate. Based on data from the U.S., Australia, and the U.K., the largest number of Indian students abroad are studying at the graduate level. In the U.S., 60 percent of Indian students were studying at the graduate level, mostly in master’s degree programs, in 2023/24, according to IIE Open Doors.

The U.S. is really the only major destination for which we have publicly available national data on fields of study broken down by nationality, thanks to the work of IIE. In 2023/24, about 43 percent of Indian students in the U.S. were studying the group of disciplines labeled “math and computer science.” (Within this grouping, most were likely studying computer science and information technology.) This is proportionately much more than among any of the other top 25 countries of origin. The next most chosen fields of study were engineering (25 percent) and business and management (11 percent). These three fields make up almost 80 percent of all fields of study among Indian students. The trends elsewhere are likely similar.

Another way to approach this topic is by looking at credentials these students hold when applying for education abroad. Credential evaluation data from World Education Services (WES) for those applying for educational pursuits in Canada and the U.S. diverges slightly from overall trends. The top majors evaluated among Indians pursuing education in 2024 were, broadly, Computer Science and Engineering, Business Administration, General Academic, Dentistry, and Electronics and Communication Engineering. The top four credentials evaluated were Bachelor of Technology, Bachelor of Engineering, Bachelor of Science, and Bachelor of Commerce. Most of these prospective students were likely applying to master’s degree programs.

The Big Four: What Are the Factors Driving Declines from India?

As noted, the U.S. and the U.K. have recently registered declines in Indian applications and enrollment according to official sources. Canada is widely expected to experience international enrollment decline this academic year. At the same time, Australia is purposely lowering the number of international students allowed into the country. Policies in these countries have driven many of these drops, but other factors are playing a role, too.

Restrictive International Student Policies

One of the most significant developments has been the rise in proposed and implemented restrictive policies toward international students in the Big Four, in large part a response to souring public sentiment in regard to immigration. In Australia, the U.K., and the U.S., immigration has long been a contentious political issue. Canada has until recently managed to achieve greater consensus around the topic, but it has become a major issue in recent years, with many in the public believing that the large numbers of immigrants coming into the country were driving housing shortages, among other challenges. Australia, Canada, and the U.K. have already implemented at least some policy changes. The U.S. is likely to follow suit under the new administration of President Donald Trump. All such policies aimed at international students will have a particularly strong impact on Indian students, the top international student group in Canada, the U.S., and the U.K. and the second largest in Australia.

In Canada, there have been a flurry of policy changes towards international students, beginning in late 2023. These myriad changes, which we’ve explored in articles in May and November 2024, include strict caps on the number of study permits issued per province, more than doubling the required amount of funds that incoming students are required to demonstrate they have, and stricter limitations on the right of spouses to work while in Canada. These caps and limits come alongside changes in Canada’s overall immigration system, including limits in the number of new immigrants invited to come to the country.

Like Canada, Australia has been in the process of instituting strict policies towards international students. Similarly, the main goal is to reduce overall immigration, with a specific goal of cutting net migration in half by this year. Cost-sensitive Indian students have been particularly hard-hit by a significant hike in the visa application fee, now considered to be the most expensive in the world. The government also introduced international student caps: In 2025, international students will be capped at 270,000, with some exceptions.

The U.K., under the previous government, introduced a ban on most international students bringing dependents – spouses or children – that went into effect at the beginning of 2024. It has been credited with causing the decrease in student visa applications in fall 2024, at least partly. Meanwhile, in the U.S., there was relatively little change in international student policy under the administration of President Joe Biden. The new Trump administration, however, is more likely to rethink international student and related policies as part of a tougher stance on immigration more broadly. The administration could be partly inspired by efforts in places like Australia and Canada.

Few policies so far target Indians specifically. However, in 2023, several universities across the Australian states of New South Wales and Victoria began banning student recruitment in the Indian states and union territories of Punjab, Haryana, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand, and Uttar Pradesh over allegations of visa fraud. Across the Indian media, there are numerous analyses of changes to these policies and how they will impact students. The sum total of these policies will likely depress Indian enrollment in these countries for some time.

Narrowing Opportunities for Post-Graduation Employment and Permanent Residence

Opportunities to work, particularly after graduation, are a major pull factor to any host country and institution for Indian students. Likewise, for a smaller number of Indian students, opportunities to transition to permanent residence can make a destination particularly popular. Traditionally, the Big Four have offered some opportunities for both to varying degrees. On the more generous end in recent years has been Canada, which has historically provided more opportunities for international students to obtain permanent status in the country. The most recent iteration of the Canadian Bureau for International Education’s (CBIE) International Student Survey in 2023 found that 68 percent of Indian students wanted to obtain a post-graduation work permit to work in the country after graduation. Forty percent wished to eventually apply for permanent residence in Canada.

By contrast, the U.S. has been one of the more restrictive destinations. Depending on their visa, field of study, and level of study, students can stay and work full-time in the U.S. after graduation for anywhere from one to three years. The opportunities to stay on permanently, however, narrow considerably after that. The main way to do so is through the H-1B visa, a temporary work visa that, with some important exceptions, requires employers to sponsor the worker and which is drawn through a lottery system due to ceilings instituted by the president. From there, some H-1B visa holders may be able to obtain a green card (permanent residence). (More than 70 percent of H-1B visa holders are Indian, by far the most of any country.) Most other pathways are considerably narrower.

The various post-graduation work schemes have always been subject to political considerations, and policies have changed with time and circumstances. Currently, however, all four countries are either considering restrictions on international students in terms of work and permanent residence or they have already enacted such policies. These policies will likely impact the attractiveness of these destinations to Indians, who highly prioritize gaining work experience and, for a smaller number, pathways to immigrate.

In December 2023, Australia announced a return to the original lengths for its Post-Study Work Visa: two years for undergraduates and four for master’s degree students. This ended an extension program that allowed international students to work after graduation in key sectors for up to four years for undergraduates and five for master’s students.

For the moment, work programs in the U.K. and U.S. are remaining in place. The U.K. Government’s Migration Advisory Committee recommended retaining that country’s current program, known as the Graduate Route visa, which gives international students two years to work. The U.K.’s International Education Strategy, released by the previous Conservative Government (led by then Prime Minister (PM) Rishi Sunak), is being reviewed by the current Labour Government (under PM Keir Starmer), as of October 2024.

In the U.S., Optional Practical Training, or OPT, the main form of post-study work authorization for F-1 student visa holders, remains. The future of OPT under the new Trump administration, however, is unclear. Trump and his officials have so far said little, but there were attempts in the first Trump administration (2017–2021) to curtail the program. The administration may choose to do so again. Similarly, the Trump administration is likely to restrict the H-1B visa program, despite a comment that then candidate Trump made in summer 2024 that international graduates of U.S. institutions should automatically receive a green card.

Visa Delays and Denials

All four countries have struggled with delays in processing student visas in the last year or so as demand has bounced back heavily. This can delay the start term for some students, and some may be frustrated enough to abandon the process. In some cases, Indians are particularly affected.

As part of its goal of drastically reducing migration, Australia has significantly increased its visa refusal rate, and processing times are now significantly longer, according to reporting from The Guardian. In general, the government is attempting to crack down on “backdoor visas”—individuals applying for a student visa with the intention of working or immigrating instead. To accomplish this, there is a tiered system of Australian universities from 1 to 3; those labeled 1 are considered “low-risk,” for which visas are processed faster. Recently, nine universities were downgraded from level 1 to 2, and two others were downgraded to level 3. Institutions in levels 2 and 3 are reported to be facing significant financial hardships due to the increased delays and refusals. It’s believed that the university recruiting ban on certain Indian states is largely a result of this system. In July, Times Higher Education reported that one in three Indian student visa applications to Australia was rejected, and one in five applications overall was refused. Additionally, processing times had tripled.

In the U.S., visa denials and delays among international students writ large have been well-known. U.S. institutions cited it as the top reason for any decreases in international enrollment at their institution in fall 2024, according to IIE’s Fall 2024 Snapshot. A recent analysis conducted by Shorelight and the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration found that visa refusals were a major problem particularly for students from Africa and to a certain extent South Asia, as well as a few select other locales. An article from Inside Higher Ed also reported that Indian students were disproportionately affected by visa processing delays in 2024.

Canada recently ended its Student Direct Stream program, which expedited processing of visas for Indian students and some others, slowing down the process for many applicants. Processing of Indian applications to Canada has also slowed due to reduced staff levels in Canadian diplomatic posts in India following recent bilateral tensions (discussed below).

Affordability Challenges

In many surveys of prospective Indian international students, finances are the chief concern. For example, in QS’s (Quacquarelli Symonds) From India to the World report, based on results from its International Student Survey 2024, the cost of living was, by far, the biggest concern among Indian students, at 70 percent. The next two concerns were also related to finances: employment and availability of scholarships. When selecting the location of the study, the cost was second only to safety, according to the report.

The funding challenges for international students, and specifically Indian students, have long been known. In the U.S., while some recent reporting has suggested that the actual cost of college attendance (as opposed to the stated price) has actually leveled off or fallen in recent years, international students typically contend with higher fees relative to what many of their domestic counterparts pay. Those who attend a public institution, which most Indian students attend, as out-of-state students, are required to pay double or triple the in-state tuition price. They are unable to access the same funding opportunities as U.S. domestic students from the federal or state governments and even from many private lenders. The cost of living is often as big a challenge. In IIE’s Fall 2024 Snapshot, the cost of attendance was the second biggest factor driving enrollment declines at individual institutions, after visa delays and denials. It may also be a prime factor in why less expensive Texas beats out California and New York, the top two states for international students overall, to be the top hosting U.S. state for Indian students.

The relative weakness of the rupee, India’s currency, against major destination currencies and the lower income of most Indian households makes affording an education in a place like Canada or Australia daunting. Reports from the Indian media show many families applying for loans at a higher rate and considering cheaper destinations. Inflation, the strengthening of currencies such as the U.S. dollar, and the higher cost of living, particularly in major metro areas where international students study in large numbers, add to the affordability challenges for Indian families.

Overall, Indian students and their families are savvy consumers when it comes to international education, given the high cost. As QS notes, “With the increased cost of living and studying in major destination markets like the UK, US, Canada and Australia, universities must show how a degree results in a strong return on investment – especially when trying to appeal to Indian students, who are clearly cost sensitive.”

Safety Concerns and Perceptions about Being Welcomed

Safety has long been a top concern of Indian students and their families. In QS’s recent From India to the World report, nearly half of all Indian respondents cited safety as a top consideration in choosing a study location. The Indian media frequently report about individual deaths of or attacks on Indian students in other countries, and these appear to be having an impact. For example, a spate of attacks on Indian students in Australia, mostly in Melbourne, around 2009 and 2010 was partly credited for a drop in Indian students coming to the country shortly after. That decline lasted for several years.

It’s not apparent that there have been dramatic changes in the safety of Indian students in the Big Four. However, there has been significant reporting in the Indian media following a number of deaths and violent attacks on Indian students abroad by the Ministry of External Affairs. Most deaths of Indian students abroad appear to be from medical problems or accidents, but deaths from attacks are reported as a separate category. Even Canada, long known as one of the safest destinations, has undergone more scrutiny recently, as the largest number of deaths from attacks occurred in that country according to the government’s report. (The fact that Canada has the most Indian students of any country is, of course, a factor.)

Highly related to safety is the need to simply feel welcome in a destination. Among many Indian students, perceptions around this change with time. Canada, usually seen as one of the most welcoming countries, has perhaps suffered a setback among Indian students due to a diplomatic row between the two countries. The most recent troubles started in late 2023, when a Sikh separatist leader, a Canadian citizen, was assassinated in British Columbia. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau blamed the death on the Indian government. Since then, both countries have recalled their own diplomats and expelled those of the other. This has increased the perception that Canada is a less than welcoming place for Indians, at least in some reporting from the Indian media.

Other Destinations

Most current surveys of prospective Indian students show that the Big Four continue to be the top destinations of interest. And despite drops in numbers in these countries recently, the numbers of Indians going are still significant. That said, it’s also fairly evident that increasing numbers of Indians are looking to other destinations, driven mostly by the issues cited above.

To be clear, Indian students have been going to other destinations for some time. For example, prior to the Russian invasion in 2022, there were approximately 18,500 Indian students studying in Ukraine, making it one of the top destinations. Most were studying medicine. Most were evacuated at the beginning of the war, and about 1,100 have since returned, as of 2023.

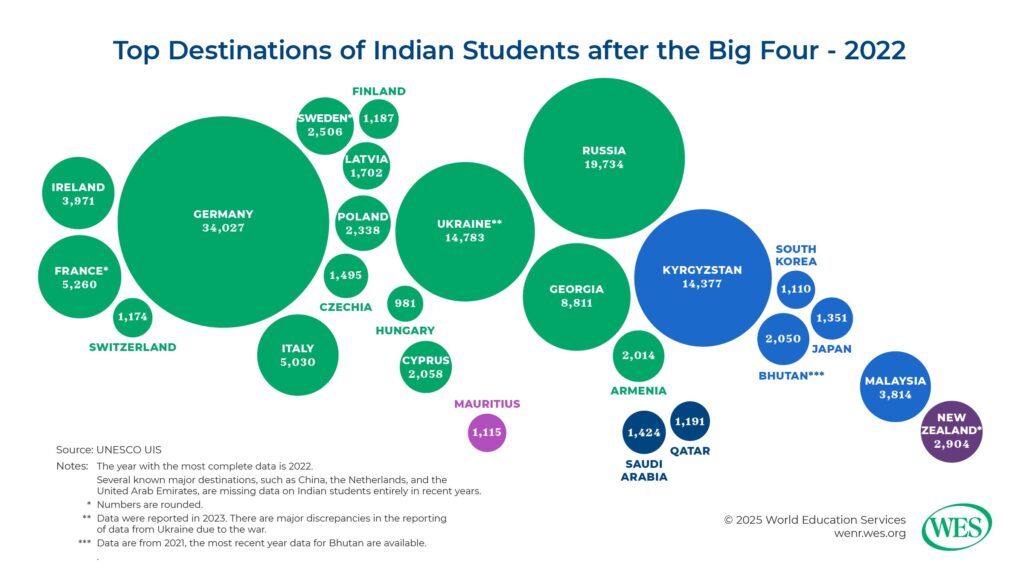

Currently, outside of the Big Four, Indian students are spread across Europe, the Asia-Pacific region, and the Gulf States mostly. According to UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the top destinations after the Big Four in 2022 (the year with the most complete data available) were Germany, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Georgia, France, and Italy. However, several known top destinations – including China, the Netherlands, the Philippines, and the United Arab Emirates – were missing data for that year. Various reports from across the international education sector and the Indian media tout various destinations that Indians are turning to, many of which are experiencing record growth. These destinations are typically more affordable, are often considered welcoming of international students, and offer a good quality education, increasingly in English. As the Big Four become more expensive and more restrictive, they may lose market share to these emerging destinations.

Destination India: Toward Becoming a Major Host of Students

India itself has sought to become a major destination for international students from around the world. There are clear benefits to a nation hosting students from other countries. These can include the income resulting from international students paying fees and living expenses, institutional and national prestige (including advancement in international university rankings), and the soft power that often accrues when students spend a significant amount of time in a country and develop ties to and affection for it. There are also internationalization benefits, including exposing domestic students to different cultures, languages, and perspectives. For India in particular, the main impetus is to increase its soft power and global stature, according to N.V. Varghese and Eldho Mathews.

Currently, India is not a major destination. According to an analysis of available data from UNESCO Institute for Statistics, India is only roughly the 32nd top host, sandwiched between Portugal and Hungary, significantly smaller countries. (The data, however, are very imprecise, and several important countries are missing data.) The Ministry of Education’s All India Survey on Higher Education, 2021-22 (AISHE) listed the number of foreign students in the country at 46,878. Since about 2015/16, this number has hovered around 45,000–47,000 students, according to the annual AISHE reports, indicating little growth.

The AISHE report for 2021/22 notes that international students came from about 170 countries. All but two of the top 10 countries, which collectively account for about 65 percent of international students, were neighboring South Asian countries or in sub-Saharan Africa: Nepal (which accounts for over one-quarter of all international students in the country), Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nigeria, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Sudan. Students from these countries are likely attracted to India for the low cost of receiving a good education, and for South Asian students, the geographic and cultural proximity also certainly play important roles.

The other two countries in the top 10 are the United States and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). These two wealthy countries are the top migration destinations for Indians overall, such as temporary workers and those pursuing permanent residence. Among U.S. students, a significant portion are likely short-term “study abroad” students who are earning credit back at a U.S. college or university. According to IIE’s Open Doors data, 1,355 U.S. students were studying as part of short-term programs in India in in 2022/23. Another segment of the U.S. population could be Indian Americans returning to study in the country of their heritage, though little data or research exists. (There has been a trend of return migration among younger Indian Americans in particular.)

India has made extended efforts to attract international students at least as early as 2018, when the Study in India initiative was launched. In addition to web portal and recruitment efforts, the initiative aimed at making India an attractive study destination through such efforts as tuition waivers for students with certain SAT scores and scholarships. The Indian government has made more recent changes designed to facilitate more internationalization and inbound student mobility. In January 2025, a set of new student visas was announced, with the intention of streamlining and simplifying the process for incoming international students. Also, the 2023 decision by the University Grants Commission (UGC) to allow in branch campuses of international universities may incentivize more international students to study in India, as well as keep some Indian students at home.

Currently, about three-quarters of all international students pursue studies at the undergraduate level, while conversely, most Indian students who go abroad do so at the graduate level (master’s or doctoral levels). There currently may be adequate capacity for international students, particularly at the undergraduate level. But one potential challenge, especially as domestic enrollment grows, is the same that incentivizes many Indian students to go abroad for education: the number of seats in quality programs available. In fact, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has stated that not only does he want to provide more incentives for Indian students to stay and study at home but also to attract more students from abroad, according to reporting from The PIE News. Part of the response to this challenge from Modi’s government is to set aside seats specifically for international students, though it’s unclear how this will impact domestic enrollment.

Probably the more fundamental challenge is the prestige factor. None of India’s institutions appear on the top lists of the most prominent world university rankings, such as the Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings or the QS World University Rankings. For example, in the THE World University Rankings 2025, the top-ranked Indian institution, the Indian Institute of Science, ranks only in the 201-250 category. The next set of institutions does not appear until the 401-500 category. (By contrast, two Chinese universities now appear on the Top 25 list.) Global university rankings are an imperfect way to gauge prestige. But in general, to attract more international students, India will need to make its institutions household names globally and its higher education system overall top of mind for those seeking higher education outside their home country.

That said, India certainly has a value proposition, at least to certain segments of students. While it does not currently have any institutions in the top echelons of the major international university rankings, there are still some Indian institutions that are reasonably well ranked and highly regarded, notably the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs). Certain fields of study, such as information technology, computer science, and business, would be of particular interest to some students from abroad. More students from lower-income countries, particularly from around Asia and Africa, and from lower income brackets could be more attracted to India due to its low-cost, high-quality (at least among some) institutions that teach primarily in English. India could also become an attractive destination for short-term, study abroad programs, particularly for students from wealthier countries, as India becomes a growing player on the world stage. Furthermore, members of the substantial Indian diaspora, such as Indian Canadians and Indian Americans, and even other South Asian diasporas, could be drawn back to the country, in large part because of family and cultural ties.

Overall, if India is able to overcome some of the basic challenges that push many of its own citizens to pursue studies abroad, it could become a major destination for international students.

Looking Ahead

In the 2020 National Education Policy, India aims to bolster gross enrollment in its higher education institutions to 50 percent, up from about 33 percent currently. This is a massive undertaking, even though the growth of the youth population in India is set to slow. If the country is indeed able to increase the number of seats, specifically in high-demand fields such as technology and medicine, and increase the quality of institutions and programs, it may slow the outflow of students from the country. India could potentially harness expertise in artificial intelligence (AI), cybersecurity, and other increasingly in-demand fields to become a destination for study in those areas. The main marker of quality will be the ability of students to find good jobs commensurate with the education they receive.

In the meantime, large numbers of young Indians will look for opportunities for higher education abroad, and a subset of those will look to stay permanently. Countries in the Global North, including the Big Four, ultimately need international students, some of whom can become immigrants, to benefit their own higher education systems and economies. Politics is often what gets in the way.

The potential of India – on all fronts – is tremendous. It has a youthful, highly talented population ready to work and contribute. The opportunity for a good quality higher education, whether at home or abroad, is the key factor for many.

1. See Mehra, A., & Kaur, T. (2022). Flight for greener pastures: a look into international migration of Indian students. International Journal of Economic Policy in Emerging Economies, 15(2-4), 164-174.

2. This is based on a rough calculation of national data sources and the figure of 1.3 million cited by India’s Ministry of External Affairs, as reported by The PIE News.

3. SEVIS data is released in monthly batches. This analysis compared November 2023 and November 2024 as proxies for Fall 2023 and Fall 2024 respectively. Numbers from month to month within a given term generally change little.