$39.4 Billion: The Money We Miss by Under-Employing College-Educated Immigrants

Mia Nacamulli, Global Talent Bridge, WES

At a time when America is actively wrestling with how best to address skilled immigration and worker visa policy, it’s worth assessing the value (or rather, the missing value) of skilled immigrants already in our midst. The numbers at play are eye-opening.

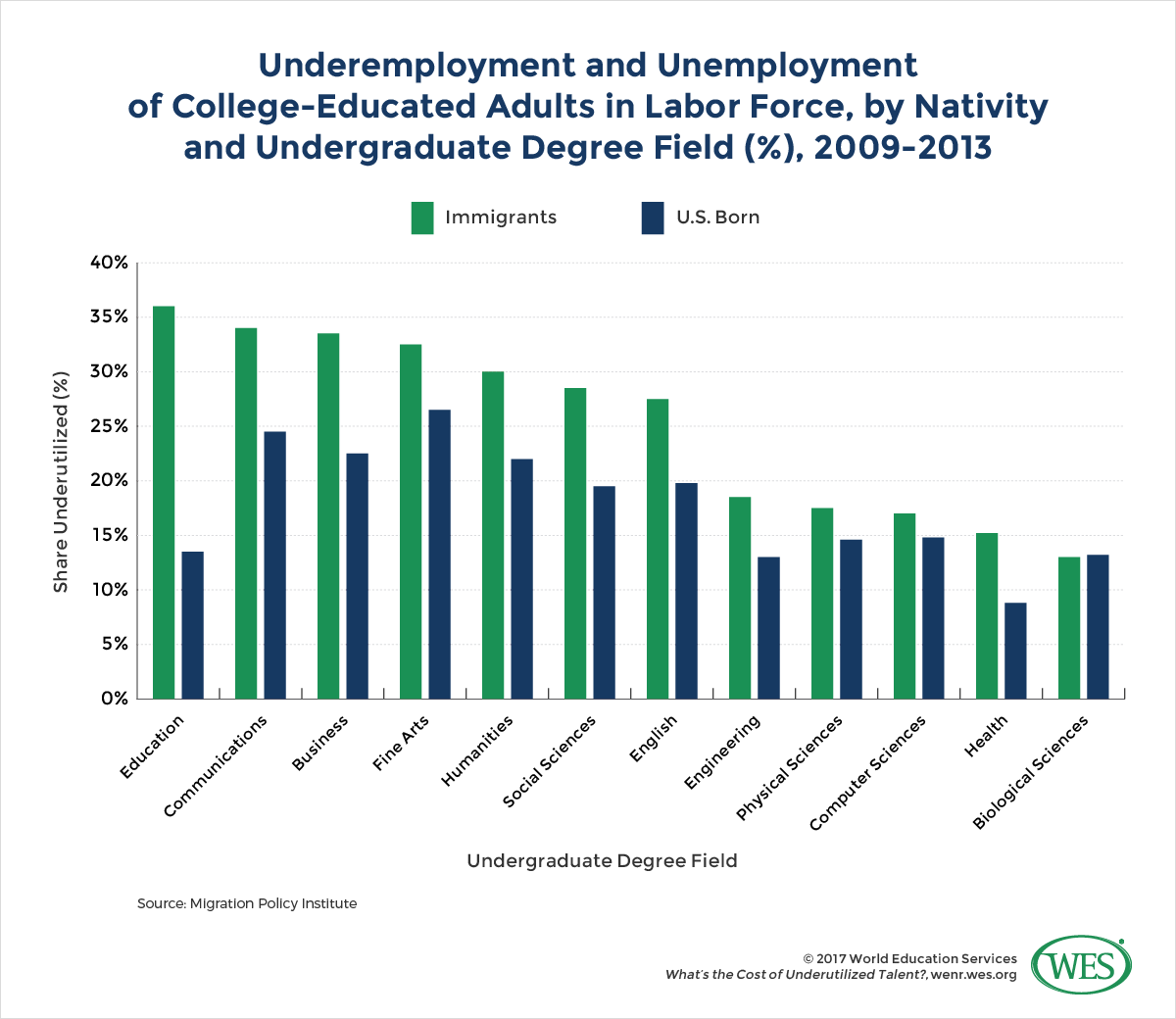

For the five years spanning 2009 to 2013, one quarter of the 7.6 million college-educated immigrants in the U.S. were either unemployed, or working at unskilled jobs well below their skill levels – a phenomenon known as brain waste. Among those were almost 470,000 immigrants with training in engineering, biological and other sciences, technology, engineering and math – a group that could, with minimal support, help employers hire for many of the chronically hard-to-fill STEM positions.

Employed at their skill levels, these underemployed immigrants, 1.9 million of them in total, could have generated about USD $39.4 billion in earnings each year. They also could have contributed an estimated USD $10.2 billion in taxes back to their communities each year.[1]Untapped Talent: The Costs of Brain Waste Among Highly Skilled Immigrants in the United States was produced by WES, New American Economy (NAE), and Migration Policy Institute (MPI).

Neither has happened thanks to underemployment — or more colloquially, to “brain waste.”

In December, WES, the Migration Policy Institute, and New American Economy released a report called Untapped Talent: The Costs of Brain Waste Among Highly Skilled Immigrants in the United States. The report is the first of its kind to put a price tag the contributions that highly skilled immigrants could contribute to our economy if they weren’t drastically underemployed.

The findings, which address the issue of employment among skilled immigrants, are highly relevant at this time. The short term context is uncertainty over the H1-B visa program, the flight of highly skilled foreign workers to Canada, and lingering questions about other programs that provide a pathway to work for college graduates from other countries. The larger frame of reference is an increase in the percentage of skilled immigrants among recent U.S. arrivals.

Between 2011 and 2015, for instance, fully 48 percent “of immigrant adults who entered the United States were college graduates,” as the authors of Untapped Talent note. This percentage represents “a sharp rise” over pre-1990 figures, when just over a quarter (27 percent) were college educated. It’s also a notable increase over pre-recession rates, when about a third of all immigrants to the U.S. (33 percent) were college-educated. Given expectations that the trend will continue, we face even greater potential losses unless we take corrective action, and help these skilled immigrants find a way to put their skills to work.

Background

What is brain waste? At its most basic, the term refers to a mismatch between skills and training, and employment. The classic example is a trained doctor who cannot find work in her field, but instead works as cashier or taxi driver. Ditto the engineer who busses tables, or the computer scientist who works as a janitor.

The authors of Untapped Talent further narrow their definition, noting that brain waste (or “skill underutilization”) comprises two “unfavorable labor market outcomes”:

- Unemployment, which “occurs when a person who is actively searching for employment is unable to find work”

- Underemployment, which “refers to work by the highly skilled in low skilled jobs [which typically require a high school diploma or less],… e.g., home health aides, personal-care aides, maids and housekeepers, taxi and truck drivers, and cashiers.”

The analysis in Untapped Talent focuses only on those who are severely “underemployed in positions substantially below their level of training.” Although it addresses brain waste among both immigrants and underemployed native-born Americans, the bulk of the report focuses on the challenges facing immigrants, the costs of failing to integrate them into the workforce, and finally, on potential solutions.

Causes of Under-Employment

Why are skilled immigrants unable to find work that matches their capabilities? Untapped Talent identifies several critical factors. Among them are:

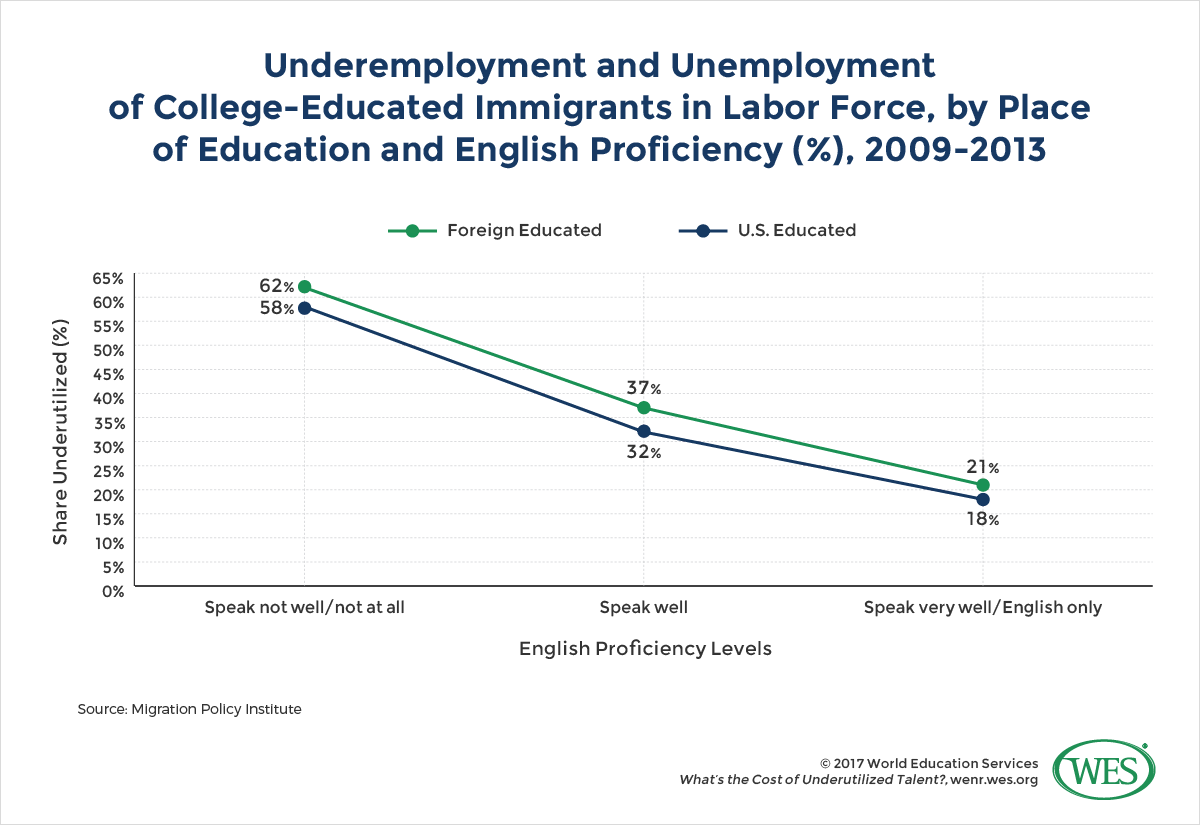

- Language skills – Low English proficiency is perhaps the most critical barrier to employment in the United States. Skilled immigrants who “reported speaking English ‘not well’ or ‘not at all’ were five times as likely to be in low skilled jobs, as compared to English-only speakers. Even those who reported speaking English “well” were twice as likely to be in low skilled jobs as compared to English-only speakers.

- Place of education – Having a foreign degree instead of a U.S. degree decreases the chances that immigrants will find jobs that match their skill levels – possibly owing to perceptions of the quality of foreign education and transferability of foreign credentials. According to researchers, “immigrants educated abroad accounted for 60 percent (or 1.2 million) of the 1.9 million foreign born who were either unemployed or underemployed” from 2009-2013. About 21 percent – 399,000 – of the remainder of those suffering brain waste were U.S. educated immigrants. The remainder were U.S. educated natives.

- Degree level – The less higher education an immigrant has, the less likely they are to find employment that matches their skill level. “Immigrants with doctoral degrees were 80 percent less likely to work in low-skilled jobs than their Bachelor’s-holding peers. A high degree of subject specialization among advanced degree holders likely increases their employability in more highly skilled jobs.

- Country of origin or ethnicity – College-educated Africans and Latin Americans are far more likely to be in low-skilled jobs than their Asian or white counterparts, according to the report. “Among foreign-educated immigrants, 47 percent of Mexicans, 44 percent of those from the Caribbean, and more than 35 percent of Africans, South Americans, and Filipinos were underemployed or unemployed,” note the authors. Brain waste was lowest, by contrast, among immigrants from Canada, China, the European Union, Australia, and India, whether educated in the United States or abroad, in part because many arrived on temporary employment visas, such as the H1-B, aimed at highly skilled workers.

Remedies

There are some obvious target areas where skilled immigrants, especially those with more advanced training, can be put to work. Consider healthcare. As The Atlantic noted in 2016, “Between 2010 and 2030, the population of senior citizens will increase by 75 percent to 69 million,” meaning one in five Americans will be a senior citizen; in 2050, an estimated 88.5 million people in the U.S. will be aged 65 and older. And as the population ages, demand for health-care services will soar. About 80 percent of older adults have at least one chronic condition, and 68 percent have at least two, according to the National Council on Aging.

Nurses are in chronically short supply in the U.S. Meanwhile, nursing programs are over-subscribed and can’t accommodate applicants. “One main reason,” notes one industry blog, “ is that schools [can’t find] faculty to teach the curriculum. Those who have high enough credentials to teach nursing often opt for higher paying positions [as nurses.] Two-thirds of nursing schools said faculty shortages contributed to them having to turn down qualified applicants, says the [American Association of Critical Care Nurses.]”

The country also needs doctors. In April of last year, the American College of Medical Colleges released findings that “Under every combination of scenarios modeled, the United States will face a shortage of physicians over the next decade… By 2025, the study estimates a shortfall of between 14,900 and 35,600 primary care physicians. Non-primary care specialties are expected to experience a shortfall of between 37,400 and 60,300 physicians.”[2]Association of American Medical Colleges, “New Research Confirms Looming Physician Shortage,” April 5, 2016. https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/458074/2016_workforce_projections_04052016.html, accessed April 2017.

Some parts of the nation are especially affected. The Chicago Council, for instance, noted in a March 2016 policy paper, that “[the] Midwest is particularly plagued by a physician shortage [that] will be exacerbated in the coming years as the healthcare needs of retiring baby boomers strain the system.”[3]Fisher, Nicole. “Midwest Diagnosis: Immigration Reform and the Healthcare Sector,” March 2016, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/sites/default/files/2016-Midwest-Immigration-Reform.pdf. Accessed April, 2017.

“Workforce gaps also extend to lower-skilled, lower-paid healthcare jobs, such as home healthcare aides and technicians, as US-born workers choose more-lucrative positions in other industries” continues the paper. “Foreign-born healthcare workers are well-positioned to fill these gaps in the labor force (and have been doing so for years), [however] the outdated federal immigration system, along with complicated state-level credentialing requirements, pose hurdles.

The authors of Untapped Talent offer examples of programs at the local and state level, programs that address obstacles to employment by offering training, networking, and credential recognition and professional licensing services for skilled immigrants. One key example is the Welcome Back Initiative. Begun in 2001, the initiative includes 11 centers in underserved communities nationwide. These centers seek to enable internationally trained health workers living in the United States to provide “linguistically and culturally competent health services in underserved communities.”

Welcome Back Centers seek to help skilled immigrants find employment in multiple types of jobs related to healthcare: nurses, pharmacists, dental hygienists, respiratory therapists, medical laboratory technologists, psychologists, and social workers. Welcome Back Centers “provide immigrant health professionals [with] assistance in obtaining the necessary credentials and licenses to practice their profession in the U.S., marketing their skills appropriately and effectively, obtaining further education and experience to facilitate their finding of meaningful employment in the health sector, and if necessary, exploring alternative health-related careers,” especially in “community-based clinics, public health clinics, and health service agencies that are often the sole providers of health services for immigrant communities.”

These centers focus on providing the skills and services that their skilled clients need most. The Welcome Back Center in San Francisco, for instance, developed a specialized curriculum in English for health professionals. Other services provided by Welcome Back Centers include counselling for skilled immigrants struggling with loss of professional identity; assistance navigating complex licensure processes; and career counseling to help newly arrived professionals understand the range of roles and health-related professions open to them (and the licensure required for each). Critically, Welcome Back offices ensure that services are available outside of standard business hours, so that professionals who are working “survival jobs” to support their families can access needed services and not become trapped in low-end jobs that barely meet their most basic needs.

Another national organization, Upwardly Global, tackles the other side of the employment equation by pairing corporate volunteers with immigrants to help them practice soft skills that make a difference in job interviews. These volunteers, obtained through partner companies, coach new arrivals in simple practices like maintaining eye contact or forthrightly discussing their skills and talents. They also help immigrants begin to develop professional networks. Upwardly Global also helps immigrants streamline resumes.

Cities including Cincinnati, Detroit, St. Louis, and others have sought to attract and integrate skilled refugees, and states including Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania have “identified immigrant credential recognition and development as policy priorities.” Ohio and Michigan, meanwhile, have established programs to help build an education to work pipeline for international students graduating from state universities.

Why It Matters

Immigrants live and work in every community across the United States. Those communities miss out when residents don’t have income to spend — and the amount that immigrants don’t earn and can’t spend in local grocery stores, restaurants or retail outlets is considerable. A comparison puts it into perspective: “$39.4 billion is equal to the expected net profit of the entire U.S. airline sector in 2016,” as immigration policy analyst Maurice Belanger noted on the Immigration Impact blog.

And what of taxes? The authors of Untapped Talent estimate that, each year from 2009-2013, the federal government alone missed out an USD $7.2 billion in tax revenues. That amount would cover the entire 2017 budget (with hundreds of millions of dollars left to spare) for the U.S. Department of Labor’s Training and Employment services, which funds job training programs and other services to improve the employment prospects of adults, youth, and dislocated workers across America.

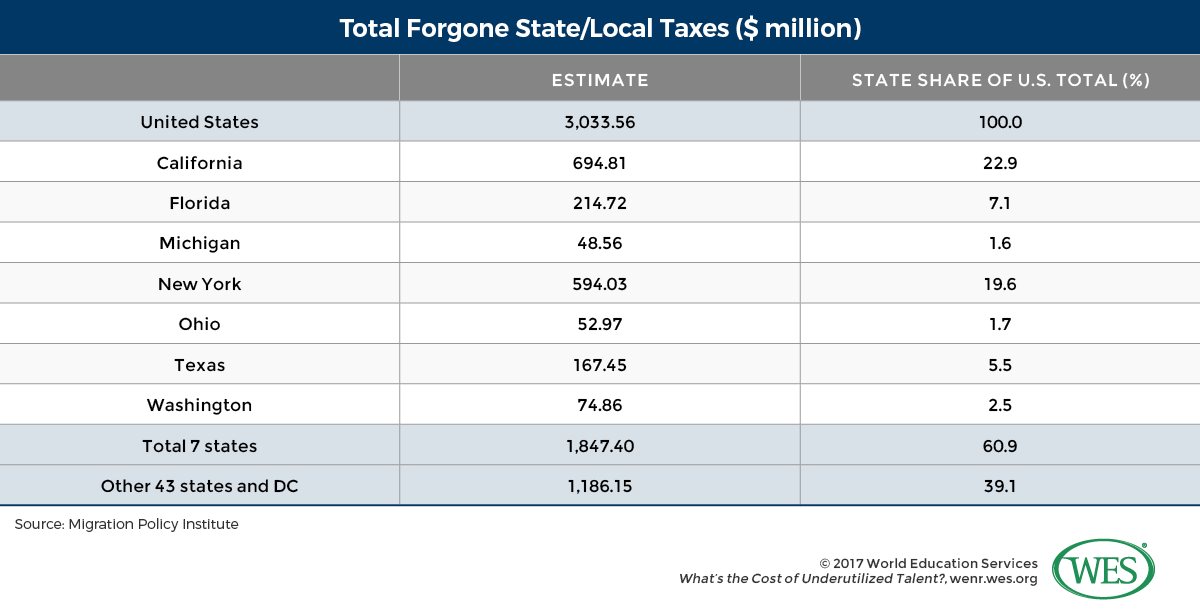

Untapped Talent also estimates that state and local governments forfeited another USD $3 billion annually. At a time when states routinely struggle to balance budgets – and to find the funds to support state higher education institutions that provide local residents with the skills needed to succeed in the workforce – such dollars are surely in need.

The implications of this brain waste extend far beyond economic impact, of course. Skills decline over time if underused, and education and experience lose relevance and marketability as they become less current. Under- or unemployment adversely affects the following generation, too – children of highly skilled immigrants have a greater chance of success if their parents gain adequate wages with proper employment.

Finding solutions to the challenge of brain-waste among skilled immigrants – whether via government policy, community organizations, or deeper insight into the value and meaning of foreign credentials – makes sense. It’s a way to take advantage of the rich human capital already here. To learn more about the issue, and download the full report, Untapped Talent: The Costs of Brain Waste Among Highly Skilled Immigrants in the United States.

The World Education Services (WES) Global Talent Bridge program conducts outreach and provides training, tools, and resources designed to ensure the successful integration of immigrant professionals. WES also hosts IMPRINT, a national coalition of nonprofit organizations that identifies and promotes best practices, and advocates for policies that facilitate the integration of immigrant professionals into the US. economy. IMPRINT can be reached via contact@imprintproject.org.

References

| ↑1 | Untapped Talent: The Costs of Brain Waste Among Highly Skilled Immigrants in the United States was produced by WES, New American Economy (NAE), and Migration Policy Institute (MPI). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Association of American Medical Colleges, “New Research Confirms Looming Physician Shortage,” April 5, 2016. https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/458074/2016_workforce_projections_04052016.html, accessed April 2017. |

| ↑3 | Fisher, Nicole. “Midwest Diagnosis: Immigration Reform and the Healthcare Sector,” March 2016, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/sites/default/files/2016-Midwest-Immigration-Reform.pdf. Accessed April, 2017. |