The Gaokao: History, Reform, and Rising International Significance of China’s National College Entrance Examination

Mini Gu, Area Specialist, and Jessica Magaziner, Research Associate

For around 9.5 million rising high school graduates across China, three days in June represent a critical turning point. That’s when the gaokao, China’s high-stakes standardized college entrance exam, is administered.

The exam was long the only admission requirement for higher education in China. Good results considerably enhance chances of admission to a handful of top-tier universities (and have a profound impact on students’ lifelong social and economic status). Poor results put students on a far less promising track.

Recent reforms have sought to diminish the importance of the exam, but it remains the primary gateway for students seeking admission to higher education institutions – especially top-tier institutions – in China. The test has also begun to gain international relevance, with up to a reported 1,000 institutions in 14 nations now accepting gaokao results for consideration in the undergraduate admissions process.

It is with an eye toward the dominance of China’s presence as a supplier of students to the global education market that this article offers an overview of the gaokao, including:

- Its role within the Chinese education system

- The history and structure of the exam

- An overview of recent reforms

- Increasing international recognition of the exam

Snapshot: Higher education in China – Few top spots, enormous demand.

China’s higher education system includes three tiers: At the top is a handful of top-tier institutions that receive billions of dollars in funding under two government programs. The programs, “Project 211” and “Project 985,” are explicitly intended to increase the institutions’ research capacity and raise their global standing. Below top-tier institutions are thousands of lower quality tier-two and –three schools.

Higher education’s role as a path to social status and employment has created a yawning demand among Chinese youth, especially for positions at top schools. One in five tertiary students in the world is Chinese, and new higher education institutions or equivalents open almost weekly to serve them.

Students are under enormous pressure to do well on China’s high-stakes college entrance exam, the gaokao, but many fail to earn the scores needed to earn top spots. Moreover, no set score acts as a “magic ticket” to the best schools. Minimum admission scores vary across institutional tiers, schools, provinces, and even across specific streams of study. Students who do not earn slots at top schools in China look to top and even mid-tier institutions abroad for opportunities to obtain prestigious degrees. Seeking to increase enrollments among these potentially full-fee paying students, many institutions in the U.S., Australia, Canada, Italy, France and across Asia have begun to accept the gaokao for admissions.

For an overview of China’s educational system at the basic, secondary and higher education levels, please see our March 2016 Country Spotlight, Education in China.

Admission to Higher Education: High Scores, High Stakes

Each year, the sheer number of students who take the gaokao, also known as the National College Entrance Examination, is stunning. In 2015, almost 9.5 million students trooped into exam centers to sit for the three-day ordeal. For students from all walks of life, the stakes couldn’t be higher: A high score is seen as a key to success in Chinese society, and for decades, gaokao scores have long been the deciding factor for admission into any institution in any tier of China’s highly stratified higher-education system. Admission to top-tier institutions is critical to students’ long-term prospects.

“Getting into a good college, such as the country’s equivalents of Oxbridge, Beijing’s Tsinghua, or Peking University, can lead to jobs with western corporations or to elite civil service positions,” journalist Lu-Hai Liang wrote in The Guardian in 2010. “The ones who miss out will find spots in provincial universities or enroll in one of China’s less selective private institutions.” Graduates of top institutions have the ability to pursue postgraduate study in China or abroad, and to obtain high-level employment.

The consequences of being tracked into lower tier institutions can be harsh. Enrollees at “most of the ‘demand-absorbing’ …institutions at the bottom of the system” obtain a low quality education, noted researcher and international higher education expert Philip G. Altbach in a piece published earlier this year. They graduate “ill-prepared for the labor force and, subsequently, cannot find jobs.”

In other words, although the gaokao is positioned as a way to equalize opportunity and access to higher education across all economic levels, it can have the opposite effect. The result is extreme pressure to test well, often by any means necessary. Both exhaustive cramming and cheating can be routes to success. To curtail the latter, exam centers deploy tight security measures and “defensive mechanisms.” One 2015 report noted that officials in Henan Province went so far as to employ drones to derail cheaters.

The pendulum: Localization to standardization

Beginning in the 1980s, localized versions of the gaokao became common. Shanghai was the first city to customize the examination in 1985, followed by several provinces, including Guangdong, Beijing, Tianjin, Jinagsu, and Zheijiang. Until 2014, when a series of reforms introduced a standardized version of the gaokao, 16 provinces and municipalities offered customized examinations.

The standardized version of the gaokao examination is now being been out in regions throughout China. The Jiangxi, Liaoning, and Shandong provinces adopted the new version in 2015. The standardized examination will be offered in 25 provinces and municipalities in 2016. This standardization will ensure that individual gaokao results are comparable, no matter where a student sat for the test. It will also allow foreign institutions to have a better understanding of what scores mean.

The Gaokao’s Roots

For all the fervor that conversations about standardized tests generate in the U.S. educational sector, nothing holds a candle to the frenzy surrounding the gaokao. Why?

The simplest explanation is, of course, the gaokao’s overriding importance in higher education admissions. But there’s another, much deeper history at play.

As a merit-based test, the gaokao builds on the centuries-long tradition of the Keju, a civil service exam used to vet the eligibility of academicians to serve as officials in imperial China. The Keju was abolished in 1905. It successor, the gaokao was introduced as a meritocratic route to academic and social advancement in 1952, three years after the Communist People’s Republic of China came into existence.

Some 14 years later, the exam was suspended, a casualty of the Cultural Revolution, which saw the systematic closure of universities, and the marginalization and persecution of the country’s intellectual elite over the course of a decade. In 1977, the gaokao was reintroduced.

The event signaled the revival of opportunity for millions of suppressed youth in China. It also represented a commitment to evaluating students based on their academic merit rather than their political affiliations, an investment in development of a qualified workforce, and an intent to foster economic development and modernization. Millions of people signed up to sit for the exam. Only 220,000 university seats were available that year. Although the test itself has changed, it remains a gateway to opportunity for millions.

The Test Itself: Structure and Administration

The exam is administered from the 7th and 9th of June every year, and results are released by the end of the month. Test takers are typically high school students in their final year of study, but there no age restrictions.

In the cities where these tests are being administered, the entire area will be impacted. Arrangements are made to ensure that nothing disturbs test takers, including banning “noisy construction within 500 meters” of testing centers and putting all traffic police on-duty to make certain that students arrive on time. Upon arriving, students face extremely strict security measures. Fears of “wireless cheating devices” and the prevalence of “hired guns,”or professional test takers have led testing centers to go so far as using fingerprint identification. Photographs of the gaokao exam in progress show a seemingly endless sea of students, crowded into testing centers.

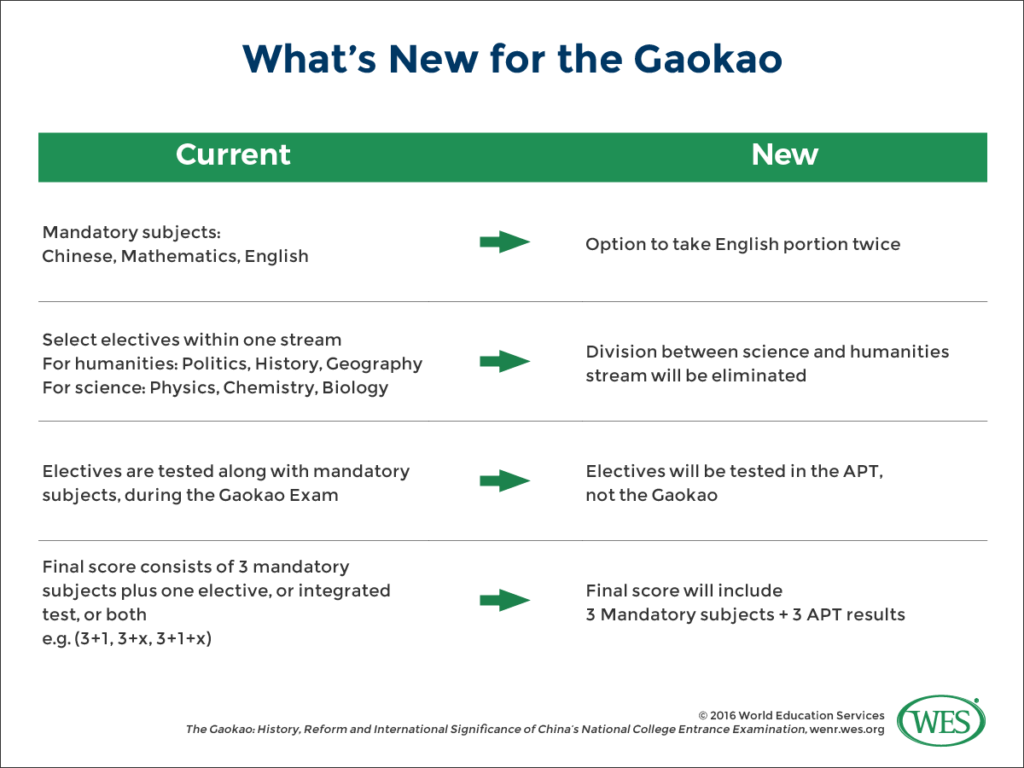

The structure of the gaokao is typically described as “3+X.” The three refers to the three required subjects: Chinese, mathematics, and English language. The “X” stands for a flexible elective component. “X” typically includes some combination of science subjects (such as biology, chemistry and physics), or humanities subjects (such as geography, history and politics.) Each province is responsible for determining the “X” components available to the students who sit for the exams locally.

2014 Higher Education Reforms

In 2014, the Ministry of Education published a series of guidelines aimed at system-wide reforms of the higher education admissions process. The guidelines encourage institutions to take a more comprehensive approach towards student admissions. They have also been framed as a way to decrease the gaokao-related stress on students applying to university. Relevant reforms include:

- A provision that allows students to take the English language portion of the gaokao twice (once in January and once in June), and to use higher score for consideration in admission.

- Removal of the requirement that students choose between the humanities and science streams in high school, and implementation of a curriculum of both humanities and science subjects. This has allowed students some flexibility in developing their secondary curriculum and the ability to take gaokao exam subjects in more than one stream.

- Removal of the requirement that electives be tested as part of the gaokao. Students may instead submit the results of the Academic Proficiency Test (APT) for electives. (The APT is administered prior to high school graduation, and has traditionally been viewed as less rigorous than the gaokao.)

- Latitude for universities to consider admissions criteria – and award ‘bonus points’ – beyond an applicant’s gaokao Such criteria include:

- awards and honors

- evidence of good citizenship, morality and ethics

- athletics

- high school grades

- teacher recommendations

The three compulsory subjects (Chinese, mathematics, and English) will continue to be a requirement of the gaokao.

International Acceptance of the Gaokao

As the dominant supplier of students to the global education market, China has a firm hold on the imaginations of international higher ed recruiters and admissions personnel globally. The millions of Chinese students who sit for the gaokao examination every year, but fail to gain admission to the nation’s top universities, present an especially interesting case: Such students are academically capable and eager for opportunity. Shut out of China’s elite schools, many may look abroad for placement. The Ministry of Education in China is also working to increase the recognition status of the gaokao in foreign education systems.

Institutions around the globe have begun to seek out such students, and to recognize gaokao scores as a valid part of an international student’s application packet. One 2015 report noted that the gaokao, was accepted by up to 1000 universities in 14 countries and regions scores as proof of academic eligibility. (Universities that accept the gaokao scores typically have additional language proficiency requirements, including interviews or additional language assessments prior to admission.)

International Gaokao Recognition: Benefits and challenges for students

Chinese students who are admitted to foreign universities on the basis of the gaokao save time and money by skipping the year of preparatory study that students planning to enroll abroad typically pursue. They also save the expense of country-specific entrance examinations, and avoid the stigma of attending lower-quality universities at home. However, Chinese students who decide to pursue education abroad only late in their educational careers may face unexpected challenges upon arrival on campus, and may require additional supports in order to succeed. Language skills are a particular area of concern.

Asia

A number of Asian HEIs accept the gaokao for admission. These include:

- All eight universities in Hong Kong and six in Macao

- 135 Taiwanese universities (as of 2014)

- At least ten public universities in Singapore, and three institutions in South Korea.

Australia and New Zealand

Up to 60 percent of the colleges and universities in Australia now accept the results of the gaokao for undergraduate admissions. This trend has grown swiftly since the University of Sydney began accepting the scores in 2012.

Europe

Italy and France’s acceptance of these scores have helped to distinguish them as welcoming countries for Chinese students. All of the higher education institutions in France now accept gaokao scores, which totals more than 180 universities and colleges.

Italian institutions have developed “bilateral education programs” through the Marco Polo Project and the Turandot Program that allow Chinese students to apply to 206 different schools.

Another 50 institutions in Spain accept gaokao scores. Many officially recognized universities in Germany are accepting these scores, though they often require additional Chinese undergraduate study before admission.

North America

Nine Canadian universities accept gaokao scores, most notably the well-regarded University of British Columbia.

Institutions in the United States have been slower to adopt the gaokao, and most U.S. bound students from China already sit for the SAT. However, in 2015, the University of San Francisco announced a pilot program to accept applicants on the basis of their gaokao results with no additional test results required. Only a tiny handful of others – including Suffolk University in Boston, St. Thomas University in Florida, and Brigham Young University in Utah – have adopted a similar approach.

Whether or not the gaokao will be widely adopted as a valid admissions test for institutions around the globe remains to be seen. Some experts say that while test results are a good barometer of student skill, the timing of the results, as well as other factors, limit applicability. “The biggest challenges don’t include finding students with good gaokao scores,” said one U.S.-based expert. Instead, major challenges include finding English-language-proficient students who opt to consider attending U.S. rather than top-tier Chinese schools based on their scores. “Finding students whose English is of a high enough standard to go straight into [undergraduate] study without extensive English classes beforehand” is a tough task,” he continued.

To learn more about the importance of the gaokao examination for Chinese students, listen to our recent webinar, “The Gaokao: Gateway to Higher Education in China.”