Addressing the U.S. Global Partnership Lag

Ian Wright, Director of Partnerships, WES

In an era of declining public investment in higher education and increasing global competition for students, a comprehensive internationalization strategy is non-negotiable for higher education institutions of every stripe. “The internationalisation of a university is no longer ‘optional’,” Alvaro Romo, secretary general of International Association of University Presidents, recently wrote. “In particular, the need to build and take advantage of real strategic international partnerships that will enhance the quality and reach of the institution should be high on the priority list of any university president.”

However, many U.S. institutions, especially those outside of the top-tier, struggle to identify and forge relationships with best-fit foreign partners. What are the barriers to building these partnerships? How have some innovative institutional leaders found strategic entry points into the international sphere? What are the costs of failing to act? This article examines each of these issues.

Why aren’t international partnerships more common outside the top-tier of American universities?

Two sets of barriers put U.S. HEIs behind the curve on penetration of the global education marketplace. The first set is internal to the institutions themselves. Governance and any mission-driven, organization-wide focus on comprehensive internationalization are often lacking at U.S. HEIs, as are supportive infrastructure and processes.

The second set of limitations is externally imposed: At both the state and government levels, the U.S. has a dearth of government policies or initiatives to promote internationalization of the higher education sector.

Both issues create a situation in which administrators and even institutional leaders often find themselves trying to forge international partnerships without a playbook.

Internal barriers

A pair of surveys in 2014 offer insight into the internal factors that leave admissions personnel and senior staff stymied when it comes to pursuing strategic international partnerships. Together the surveys point to three primary challenges. These include:

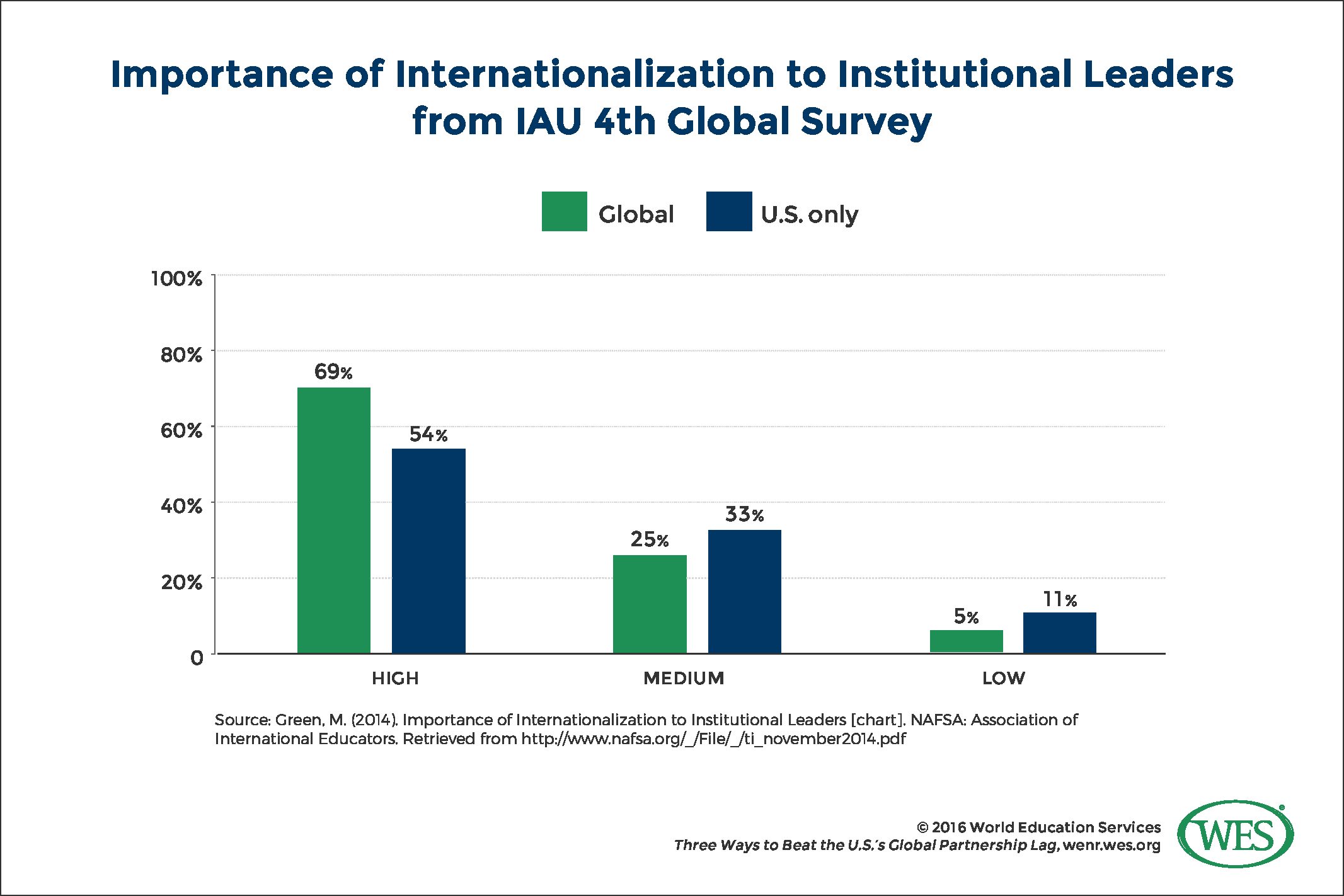

- Lack of leadership: The International Association of Universities’ (IAU) 4th Global Survey on Internationalization of Higher Education, which comprises the largest and most geographically comprehensive collection of primary data on internationalization of higher education available to date, found that U.S. respondents were twice as likely to say that their leadership viewed internationalization as of ‘low importance’ compared to respondents from other regions. Respondents from U.S. HEIs were likewise less likely than their global counterparts to describe internationalization as of ‘high importance’ to their leaders.

- Lack of mission: According to a 2014 survey by AIEA, one third of senior international officers at U.S. HEIs develop campus internationalization goals and identify global partners without any guidance from their campuses’ missions statement. The IAU survey similarly found that U.S. respondents were less likely than all others to indicate that their institution had a strategic plan for internationalization.

- Lack of infrastructure or process. The IAU survey found that many U.S. institutions lack both infrastructure and processes to support comprehensive internationalization programs. Many reported that they lack dedicated offices, budgets and monitoring or evaluation frameworks. Most also operate without explicit goals, or benchmarks for success.

External challenges

Both NAFSA and the American Council of Education’s Center for Internationalization and Global Engagement have long advocated for a federally led initiative to support the internationalization of the U.S. higher education sector. However, efforts have so far failed to coalesce. Given that adoption of their recommendations hinges on collaboration among state and national entities – and a decentralized U.S. higher education system comprised of institutions of every type – such policies are unlikely to emerge anytime soon.

When it comes to internationalization, institutions in most other nations operate within a far more supportive governmental framework. Governments in Canada and Australia, for instance, both have an explicit focus on supporting internationalization of their respective higher ed sectors; both have been gaining ground against the U.S. when it comes to attracting international students and reaping the benefits of the tuition dollars they bring with them. Both are significant destinations for international students –and increasingly competitive compared to the U.S., whose dominance of the global market has decreased by 21 percent since the turn of the century.

Canada’s governmental support of globalization

Although Canada’s provinces control educational policy, its central government actively pursues policies that position the country as an appealing choice for international students. On the one hand is its International Education Strategy, a marketing campaign which has a goal of bringing 450,000 international students and researchers to Canada by 2022. On the other is a commitment to both a skilled immigrant program and a path to permanent residency (and even citizenship) for international students.

Provincial government policies and financial incentives likewise support Canadian higher education institutions seeking to explore foreign partnerships and develop international education marketing programs. This support includes the identification of priority countries and the provision of scholarship funding earmarked for international students, as well as increased funding to maintain a sustainable, high- quality, public higher education system.

Insights from the field

For the foreseeable future, U.S. HEIs seeking to develop an international education strategy are effectively on their own – a situation that’s especially problematic for many institutions that are the furthest behind. The challenge for leaders of these schools is to develop meaningful and sustainable international partnerships with clear goals in mind – for instance, enhancing student experience and satisfaction, improving the overall quality of academic offerings at both partner institutions, building enrollment, and improving institutional reputation.

There’s no roadmap or “one-size-fits-all “ approach to successful internationalization, of course, especially for schools that are 1) are not globally ranked, 2) have limited research grants and endowments, and 3) focus primarily on professional programs and undergraduate teaching. But in terms of the benefits and “right-sized” programs, there are insights to be gleaned from institutions that have taken a scaled, innovative, and student-first approach.

CUNY – College of Staten Island sends its students to Asia Pacific University in Japan, where visiting students from campuses around the world attend classes taught in both Japanese and English. The program radically increases CUNY students’ global exposure by bringing them to a multinational foreign campus, as opposed to one filled only with students from the host country. The program represents a measured approach to establishing an international presence, and helps to improve the institution’s reputation and ability to attract students, both at home and (potentially) abroad.

Texas State University partners with Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education in Mexico to offer a joint study abroad program in which students from both institutions study in a third country. The program benefits students, who have access to the type of academic opportunities more often associated with globally ranked universities, and Texas State, which enjoys a reputational halo effect thanks to a partnership with a high-quality international partner in a neighboring community. The partnership also fills a higher civic goal, helping to foster cultural and intellectual ties across the Texas-Mexico border.

St. Cloud State University in Minnesota has a 20-year partnership with a South African institution, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. The two way partnership encourages under-represented students to participate in global learning experiences. The partnership, which is one of many for St. Cloud, also showcases the institution’s comprehensive internationalization strategy. Among the insights gained over the course of the two decade partnership is the importance of a shared commitment to sustainability. “Both partners … must be willing to contribute equal human and financial resources to ensure success” ideally “from all departments and all levels of the university,” note Nico Jooste and Shahzad Ahmad in a recent examination of the program. Clear communication and adaptability over time – the willingness to shift to changing realities, Jooste and Ahmad observe, are also critical to lasting mutual benefit.

The need to act

Until a well-funded mandate appears from state or federal agencies, U.S. HEIs must be self-motivated to strategically develop their internationalization goals and identify appropriate partners in key and emerging markets. With internationalization now a global gold standard for high quality higher education, institutional leaders need to make informed decisions about best-fit foreign partners and effective early stage program design. The challenge isn’t easy, but it can – and must – be met, and met well. Failure to act will relegate most U.S. HEIs even further back on the wish lists of foreign institutions – an outcome that serves no one.