International Branch Campuses Part Two: China and the United Arab Emirates

Chris Mackie, Research Associate, WES

Previously, in Transnational Education and Globalization: A Look into the Complex Environment of International Branch Campuses, we examined trends and push factors surrounding international branch campuses (IBCs) worldwide. In this article we continue our exploration by looking at two of the more prominent IBC host countries, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and China.

Host Country Motivations and Resulting IBC Type

The choice to establish an international branch campus is largely made by the sending institution in the exporting country. Although the home country government may provide some support, and home country accrediting agencies typically supervise the activities of IBCs established by institutions under their jurisdiction, the choice to establish branches overseas remains almost exclusively in the hands of the home institution’s governing body. Conversely, host country governments are intimately involved in the regulation of foreign education providers, both as multinational commercial ventures subject to regulations on international trade, and as higher education providers subject to some degree of quality assurance.

The policies and regulatory mechanisms adopted by the host government play an important role in shaping the structure and form taken by IBCs. In turn, these policies are shaped by historical circumstances and political, demographic, socioeconomic, geographical, and cultural factors. A close examination of national policies and rationales in both the UAE and China will help illuminate why IBCs in these two countries have flourished in two widely differing configurations.

United Arab Emirates

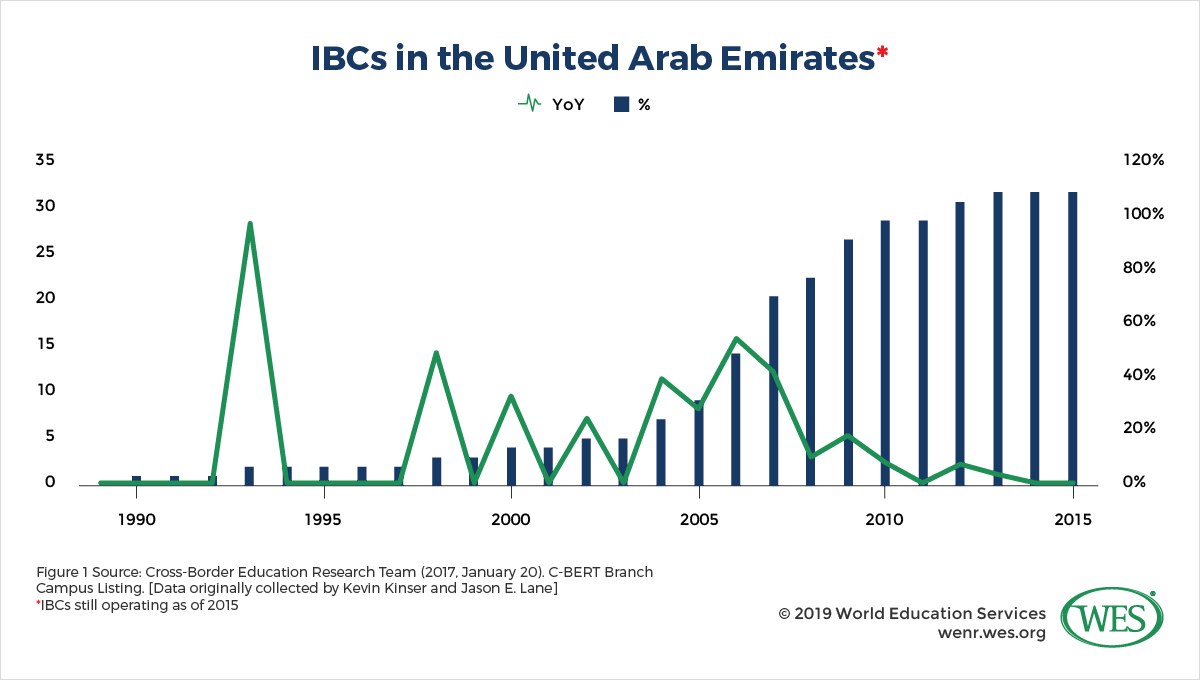

The UAE has been highly successful in its efforts to attract foreign higher education providers to its soil. Since the early 2000s, the number of IBCs hosted in-country has expanded rapidly, growing from just 4 in 2000, to 31 in 2015 (see Figure 1). Although recently surpassed by China as the top IBC host country, the UAE, with a land mass over 100 times smaller, currently hosts the largest concentration of IBCs in the world. IBCs are spread through three of the nation’s seven emirates, Dubai (24), Abu Dhabi (5), and Ras Al Khaimah (2).

Historical Context: Economics and International Relations

The UAE’s recent development—especially in the economic and political spheres since the mid-20th century—profoundly shaped the form of the nation’s IBCs. It also provides a useful context for understanding IBC proliferation in the UAE.

Prior to the discovery of commercial quantities of oil in the mid-20th century, the UAE’s importance in international affairs and the world market was marginal. Although conditions varied between emirates, in general the population was small and semi-nomadic, with exports concentrated in the pearl diving, seafaring, and fishing industries. Individual business enterprises were small, often tribal or familial affairs in which traditional techniques predominated—in some cases to the explicit exclusion of modern technology. Under these business conditions, extensive specialized training and managerial expertise were largely unnecessary.

However, the region’s central location on the oceanic trade routes connecting Europe, the Middle East, and the Far East, and its location on the southern shore of the strategically important Strait of Hormuz, increasingly attracted the attention and ambitions of the world’s great powers. In the early 15th century, the Strait of Hormuz drew the famous Ming dynasty navigator Zheng He. But increasingly it was Western European nations, and England in particular, that showed interest; until the UAE’s independence in 1971, the United Kingdom was the dominant colonial power in the region. This relationship was codified in a series of bilateral agreements between the UK and individual emirates, culminating in the 1892 “exclusive agreement.” In exchange for a promise of British naval protection for the coast and military assistance in the event of an attack by land, the emirates agreed to cede to the UK extensive control over their foreign affairs and exclusive rights to any future territorial concessions made by any of the individual emirates. Nearly half a century later, the 1939 Abu Dhabi concession agreement would similarly cede rights to foreign powers. In this case, the then ruler of Abu Dhabi granted oil exploration rights to a consortium of foreign oil companies for a period of 75 years.

The discovery and large-scale export of oil (the UAE holds the world’s seventh-largest proved oil reserves) fundamentally changed the country’s economy and society. Following the first export of crude oil in 1962, economic growth exploded, filling government coffers and funding extensive infrastructure improvements and generous welfare programs. Population growth followed, rising from 112,472 in 1962, to 3,154,925 in 2000, to 9,400,145 in 2017. Even with this rapid increase in population, and despite large fluctuations associated with oil prices and economic recessions, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita has remained among the highest in the world.

The economic takeoff also spurred the growth—or importation—of modern, large-scale, international business enterprises, the most prominent of which were the various foreign oil companies and their brokers, specialized merchants, shippers, financiers, and insurers. The massive size and highly technical nature of the industry required extensive technical expertise and managerial skills of a kind not necessary for the small-scale personal businesses that had long predominated in the region. This demand for specialized skills was reflected in the country’s rapidly rising tertiary enrollment numbers, which grew from just 519 in 1978 to 159,553 in 2016.

However, the UAE’s small, low-skilled domestic population could not meet the labor demands of the rapidly growing economy. The country began importing foreign labor, both low- and high-skilled. In fact, as recently as 2013, immigrants held more than 90 percent of the jobs in the country’s private sector. In the same year, immigrants made up over 80 percent of the population, or 7.8 million out of a total population of 9.2 million.1

Economic dependence on the export of a single, nonrenewable commodity carries obvious risks. Long-standing policy planning at the federal and emirate level has aimed at reducing those risks through the encouragement of economic diversification in order to “reduce reliance on oil and transform its economy from a conventional, labor-intensive economy to one based on knowledge, technology and skilled labor.” These policies have helped to establish the UAE as one of the most open economies in the world, designed to attract the international investment capital and sophisticated firms necessary to keep the economy rolling. This openness to international trade and the outside world also conforms to the UAE’s—and to Dubai’s in particular—historical understanding of itself as a trading nation and people.

The federal structure of governance in the UAE affords the individual emirates wide discretion in setting policies and regulations. This leeway extends to the higher education sector—making generalization at the federal level difficult. For this reason, the following discussion will focus on Dubai, the leading host emirate for IBCs.

Free Zones (FZs) and Education Hubs

Dubai’s establishment of Free Zones (FZs) is a key component of its economic policy. FZs are special economic zones which seek to attract foreign investment and commerce through the offer of financial incentives and tax and customs exemptions. In order to facilitate business opportunities, FZs are delimited geographically, each catering to a specific industry. Among the industries served by FZs is the education sector—the largest of which is the Dubai International Academic City (DIAC). To attract foreign higher education providers, DIAC offers an extremely generous incentive package and a light regulatory touch, including the allowance of full foreign ownership, full repatriation of profits, and total exemption from taxes and customs duties.

DIAC is managed by TECOM Group, a unit of Dubai Holding, the emirate’s sovereign investment vehicle; the majority shareholder is Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the current ruler of Dubai. Dubai Holding aims at creating “an innovation driven knowledge-based economy.” The establishment of DIAC is therefore a direct result of the policy objectives of Dubai’s leadership. It is both an investment promising rent revenues driven by a growing education tourism industry (IBCs in DIAC rent their campus space), as well as an investment intended to train and develop a skilled foreign and domestic workforce.

While FZs are used to attract foreign investment in many sectors of the UAE economy, similar zones specializing in higher education, often referred to as education hubs, are found throughout the world. C-BERT defines an education hub as “a designated region intended to attract foreign investment, retain local students, build a regional reputation by providing access to high-quality education and training for both international and domestic students, and create a knowledge-based economy.” Ideally, education hubs provide opportunities for inter-institutional collaborations and synergistic partnerships. Education hubs, in their specialized seclusion and critical mass of students, may facilitate the reproduction of a part of the institutional ethos and campus feel of the home institution, as examples from other countries illustrate.

Characteristics of the United Arab Emirates’ IBCs

The majority of education providers established in Dubai’s FZs are offshore institutions. In DIAC, 21 out of the 27 higher education institutions (HEIs) are from outside the UAE. Furthermore, foreign providers in Dubai rarely operate outside of FZs; as of 2011 only two providers were established outside of FZs.

International Focus

Not only are the institutions international, but the students themselves are predominantly citizens of other countries. In 2015/16, 37,692 of the 60,310 students (63 percent) enrolled in Dubai’s HEIs were expatriates. One year later, Dubai’s HEIs enrolled students from 167 countries around the world. The preponderance of foreign institutions and students reflects the composition of the country’s private workforce and population. In this connection, it is interesting to note that the UAE possesses a highly segmented education market, a situation which largely mirrors the composition of its labor force. Most UAE citizens work in the public sector and study at state or federal institutions, while foreign workers and students fill the vast majority of positions in the private sector and seats in private HEIs.

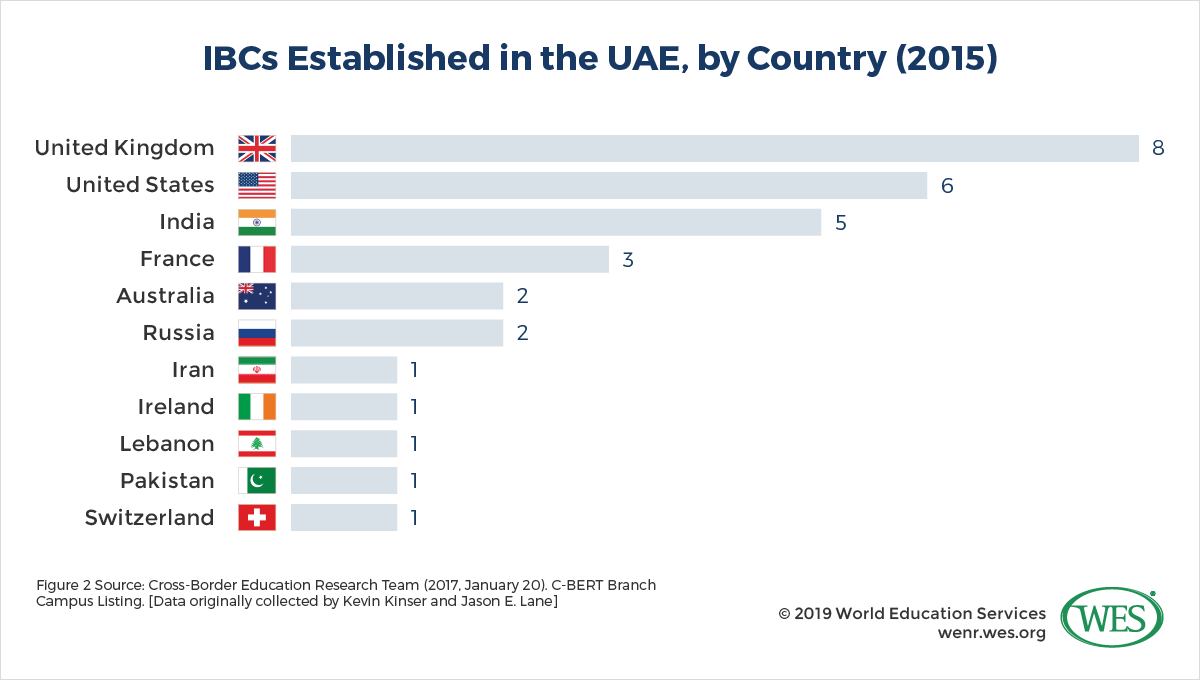

Importantly, the UAE hosts IBCs from India and Pakistan, two countries exporting very few IBCs worldwide—five of the total of seven Indian IBCs, and also the only Pakistani IBC in the world (see Figure 2). The presence of Indian and Pakistani IBCs in the UAE reflects the large proportion of citizens from these two countries in the nation’s total private workforce and population. In fact, in 2015, Indians made up 35 percent and Pakistanis nearly 10 percent of the UAE’s total population.

Market Focus

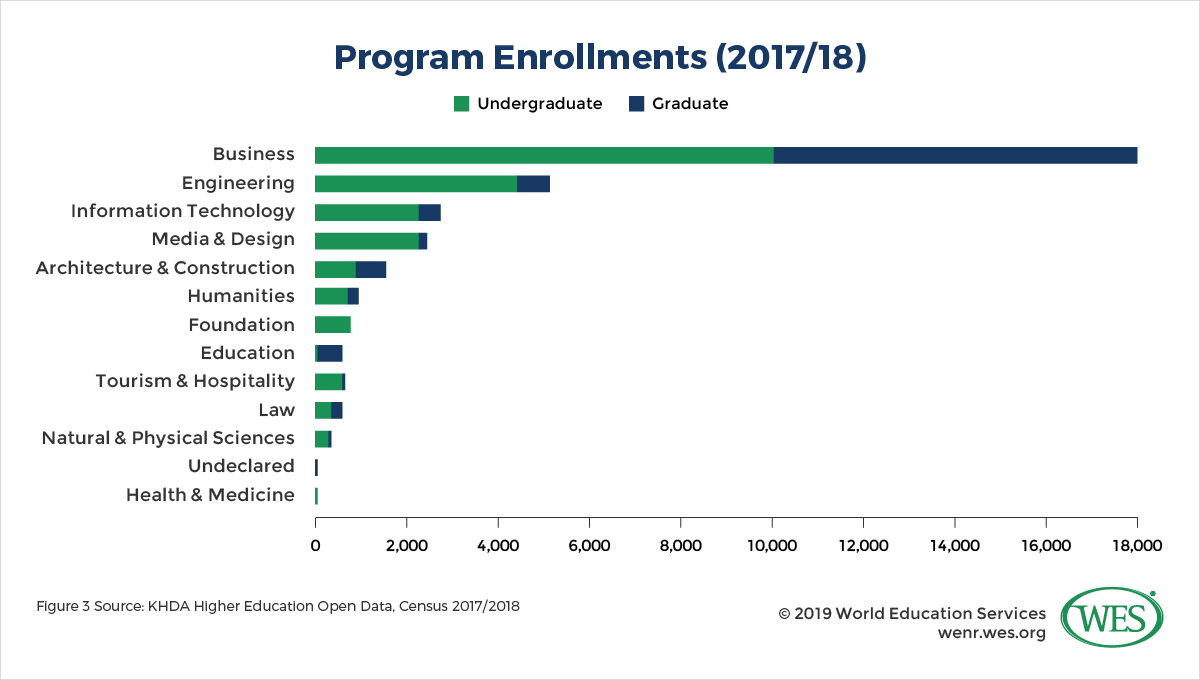

High enrollment numbers in market-oriented specializations indicate the extent to which the focus and proliferation of IBCs reflect the demands of the private labor market. Dr. Warren Fox, Chief of Higher Education at the Knowledge and Human Development Authority (KHDA), a government agency established in 2006 to supervise the development of Dubai’s private higher education, ties IBCs explicitly to market needs. He is quoted as saying, “We need more branch campuses and we need more variety.… The UAE has had a record of importing educated talent, but Dubai is diversifying its economy. It’s building a knowledge-driven economy. There are areas, such as trade, logistics and construction, where large numbers of graduates are needed.”

According to KHDA data, in the 2017/18 school year, business was the most popular specialization at all academic levels. Students enrolled in business specializations made up more than half of all enrolled students. Other market-oriented specializations, such as engineering, information technology, media and design, and architecture and construction, are also popular. These fields are critical to a region largely dependent on oil extraction and marketing. They also support the emirate’s goal of developing a workforce capable of managing modern, large-scale enterprises.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

Policies and procedures designed to regulate and guarantee the quality of IBCs vary between the different emirates. In Dubai, IBCs located within the FZs fall under the authority of the KHDA, which requires that all institutions receive academic authorization prior to opening, and that each of the institution’s academic programs be registered with the KHDA. To facilitate these operations, the KHDA established an internal quality assurance body, the University Quality Assurance International Board (UQAIB).

In line with the UAE’s open approach to foreign education providers, UQAIB itself relies heavily on the quality assurance and accreditation mechanisms of each institution, stating in its Quality Assurance Manual that,

“In order not to burden foreign HEPs [Higher Education Providers] unduly and duplicate QA processes to which such HEPs have already been subjected, UQAIB will, in the first instance, take account of existing QA reports on the quality of provision of foreign HEPs as well as the effectiveness of the QA systems and procedures in place at those institutions, as long as such reports are fairly recent.”

This model of quality assurance, known as a validation model, seeks to guarantee, with minimal intervention, that the IBC offers programs of a quality equivalent to that offered by the home institution. Among its requirements is that the IBC provide “the same accredited program taught at the institution’s home campus.”2 The stipulation that IBCs exactly replicate the programs of the home campus, removes a great deal of curricular flexibility from the hands of the IBC. But it also signals to prospective students that the programs offered at IBCs throughout the emirate are identical in both quality and content to those taught at the oftentimes prestigious foreign institutions—and thereby helps to protect the quality and reputation of Dubai’s higher education export sector.

Conclusion—Dubai, United Arab Emirates

All of these trends are in line with what a recent report of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education identifies as Dubai’s “main rationale for importing TNE provision,” namely “to allow students—primarily expats and other international students—to access undiluted quality foreign provision.” This rationale is aligned with the UAE’s strategic goals of economic diversification—through the development of its educational export sector—and the training of a high-skilled workforce for an increasingly knowledge-based economy. Recent changes made in the UAE’s visa policies are also evidence of the significance of these goals as motivating factors. In early 2019, the UAE introduced generous post-graduation work visas for international students and scholars, awarding five-year residency visas to high-performing students and 10-year visas to top specialists and researchers.

The nation’s strategic objectives have also directly shaped the form taken by its IBCs. They have promoted a market-oriented TNE or transnational education sector with educational provision taking place within internationally owned and operated IBCs—to the exclusion of nearly all other common TNE models. The UAE’s laissez-faire approach to foreign institutions, combined with its natural resources and central location in a politically pivotal part of the world, is one reason why this small nation proved so attractive as a location for IBCs.

China

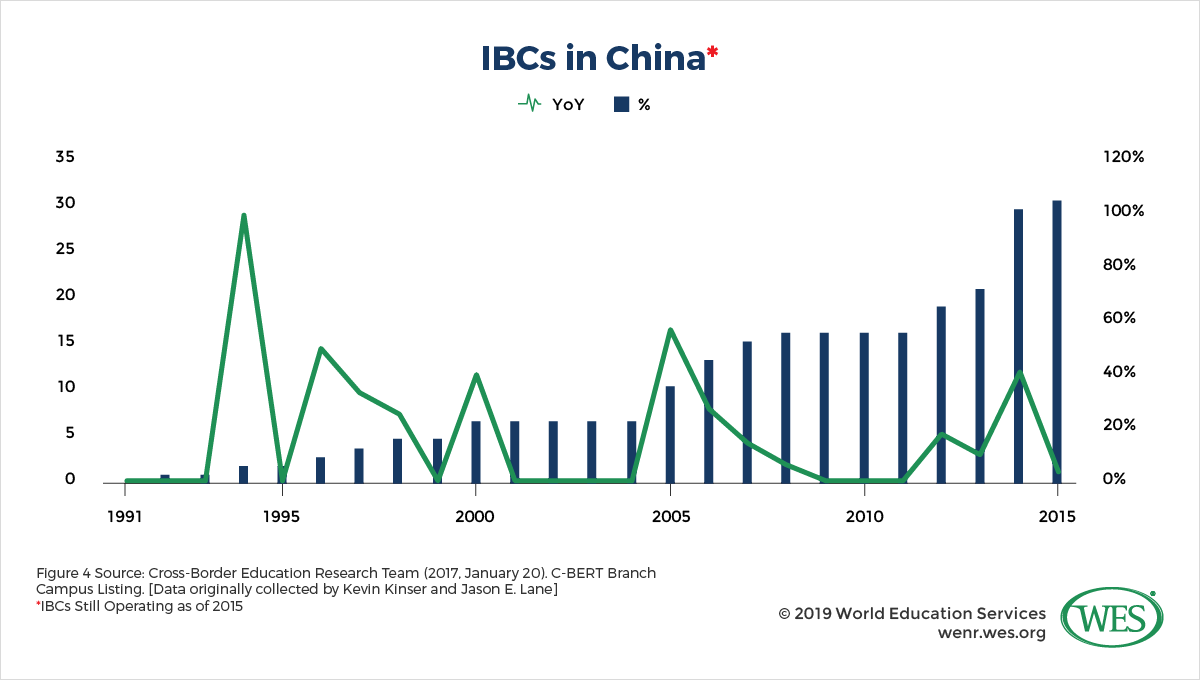

China currently hosts the largest number of IBCs in the world, recently surpassing the UAE as the top host country. Growth began in the early 1990s, although it has been far from steady. Spurts of quick expansion have been interspersed with years of stagnation (see Figure 4), a direct result of the nation’s ongoing regulatory deliberations, the specifics of which are discussed below.

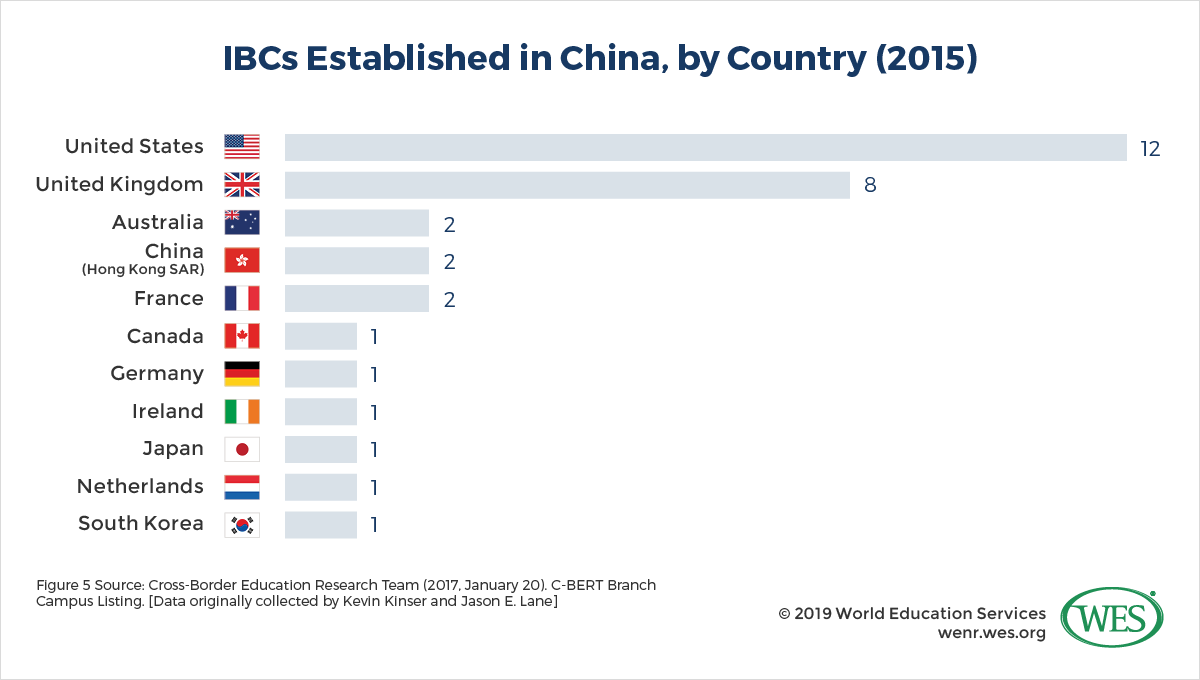

In 2015, China hosted IBCs from 11 different countries. The United States (12) and the UK (8) together accounted for 63 percent of the total. Institutions from Western countries and from industrialized Asian neighbors—Hong Kong, Japan, and South Korea—make up the remainder (see Figure 5).

Despite this recent expansion, IBCs still account for an exceedingly small portion of total Chinese HEIs and enrollments. China, with well over 40 million students enrolled in tertiary education in 2015 and only 180,000 in IBCs worldwide, barely makes a dent in meeting student demand for higher education access even with the added capacity provided by IBCs.

Historical Context: Economic and International Relations

The growing international prominence of China since the 2000s is obvious. Economically, China has become a key player in the international marketplace. In 2017, the World Bank estimated China’s GDP at USD$12.238 trillion, a more than ninefold increase since 2000. Its current annual growth rate stands at 6.9 percent, and its GDP per capita reached approximately USD$8,827 in 2017, a more than eightfold increase from its 2000 level. In 2010, China’s economy surpassed that of its main regional rival, Japan, to become the world’s second-largest economy, after the United States. It currently accounts for around 15 percent of world GDP. By 2050, although by some measures even today, it is projected to be the world’s largest economy. These developments have been accompanied by a gradual shift of the nation’s economy away from industry and manufacturing, which decreased its share of the economy from 46 percent in 2004 to 40 percent in 2017, towards services, which increased from 41 percent to more than 50 percent during the same period.

China is also increasingly looking to leverage its economic clout to expand its international political influence. A growing tendency to disregard international law in pursuit of an aggressive foreign policy is coupled with a desire to establish international institutions intended as alternatives to Western-led organizations (such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)). Most significantly, its colossal Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aims to “improve regional cooperation and connectivity on a transcontinental scale” by strengthening “infrastructure, trade, and investment links between China and some 65 other countries.”

In practice, BRI is likely to facilitate the further integration of regional neighbors into production chains—in both goods and services—centered on China, the world’s largest market. Although BRI is billed as an initiative to boost regional investment and integration, skeptics argue that it is indicative of China’s increasing reliance on “sharp power,” and that China seeks to leverage economic largesse and access to its immense market as a means of coercing regional states into alignment with its foreign policy goals. BRI is likely to have a significant impact on China’s goal to internationalize its higher education sector—as a number of its initiatives include projects and funds aimed at developing mobility and partnership programs with the country’s close regional neighbors.

China’s Higher Education Landscape

Accompanying these economic and political shifts is one of the most dramatic educational transformations of the postwar era. After the total dismantling of China’s Soviet-style higher education system during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the Chinese higher education system has expanded at breakneck speed. The country currently enrolls more students at the tertiary level than any other country in the world. The expansion of its education system truly took off in the 1990s, at the same time that the country’s economy began its incredible upward trajectory. The tertiary gross enrollment ratio increased from just 3 percent in 1990, to more than 17 percent in 2004, to over 50 percent in 2017. Over that period, gross enrollment in tertiary education grew more than 10-fold, from under 4 million to more than 44 million.

Over the past three decades, in line with its transition from a manufacturing to a service-based economy—as well as its wider political ambitions—China has devoted substantial attention to reforming and improving its domestic higher education system. In the 1990s, the country provided significant financial support to a handful of universities under its 211 and 985 initiatives, which sought to raise research capabilities and support the development of world-class universities. More recently, under the National Plan for Medium and Long-Term Education Reform and Development 2010–20 and the 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China, policy goals have included the following:

- Increasing overall spending on education

- Raising gross enrollment in tertiary education

- Improving the higher education sector in the country’s developing central and western regions

- Continuing development of world-class universities and academic programs

- Internationalizing the nation’s higher education system

The massive infusion of funds into a handful of top universities as part of these programs has yielded impressive results. However, system-wide problems remain. China’s universities are highly stratified by both function and funding, with top universities receiving a disproportionate share of government support and producing the vast majority of the nation’s advanced research. Meanwhile, the much more numerous mid- and low-tier institutions often employ unqualified faculty and offer a lower level of academic quality.

Furthermore, as the economy and middle-class has grown, demand for quality education has increased dramatically, even as available seats at top universities have failed to keep pace. This scarcity has made China’s elite universities among the world’s most selective. Although admission rates are not typically publicized, Peking University, one of China’s most prestigious institutions, likely had admission rates as low as 0.5 percent in 2012—by comparison, Harvard had a 5.8 percent admission rate for its 2017 undergraduate class.

Characteristics of China’s IBCs

It is under these conditions of increasing demand for quality higher education and expanding international ambitions that China first began to allow foreign education providers to operate within its borders. Expansion began in the mid-1990s, with a handful of IBCs established between 1991 and 2000. However, the growth of TNE and IBCs in China really took off in the mid-2000s (see Figure 4), when the current regulatory framework governing IBCs was codified in the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Chinese-foreign Cooperative Education. Significantly, this document was issued by the State Council in 2003 in the wake of commitments made by China to open its economy upon accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001.

Legal Framework

Many across the globe viewed the accession of China to the WTO as a landmark event. It seemed to promise the full integration of China’s rapidly growing economy into the rules-based international trading system. U.S. President Bill Clinton even predicted that it would have “a profound impact on human rights and political liberty.”

Although membership in the WTO and the signing of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) required liberalization of the nation’s service sector, China still retained measures designed to protect domestic industries to varying degrees throughout its economy. The opening of the education sector was no different. Full liberalization of the higher education sector was constrained by measures designed to protect China’s HEIs and support the nation’s strategic and development objectives. These intentions are clear in the wording of the 2003 regulations, which specifically stipulate that

“Sino-foreign cooperative education must be in conformity with Chinese laws, implement Chinese education policies, comply with Chinese public ethics, and may not impair the state sovereignty, security, or public interest.

Sino-foreign cooperative education shall meet the needs of the development of Chinese education undertakings, guarantee the education quality, and commit to foster a variety of talents for the socialist construction cause of China.”

The implementation of these regulations, as guided by the Implementation Measures for the Regulation of the People’s Republic of China on Chinese-foreign Cooperative Education issued the following year, implied the same overriding concerns. The measures accord special importance to both the modernization of the nation’s higher education sector and the development of the nation’s human capital by encouraging “cooperative education activities relating to the subjects, specialties and fields that are new and badly demanded in China.”

The passage of time has only strengthened China’s emphasis on protecting and developing the nation’s higher education infrastructure and national workforce. As China moved from a capacity-building phase of higher education expansion that was focused on the expansion of university seats, to an enrichment phase that emphasized the quality of higher education, it began strengthening regulations aimed at improving the quality of TNE provision in the country.

In 2007, the Ministry of Education expressed concern over what it saw as the prioritization by TNE providers of economic profit over local and national development needs. It also publicly aired its worries about a system-wide lack of regulation and quality assurance for foreign qualifications and institutions. These apprehensions led to the suspension of approvals for new foreign programs and institutions until 2010, when new regulations designed to better guarantee institutional and program quality were implemented. Regulatory oversight has continued, with the Ministry of Education announcing the closure of more than 200 Chinese-foreign partnership programs and institutions as recently as 2018.3

This emphasis on quality is also reflected in China’s increasing focus on importing only the highest ranked foreign institutions. Again, the 2003 regulations are explicit: “The state encourages the Chinese-foreign cooperative education that introduces high-quality foreign education resources.” Already, China’s most prestigious universities have almost exclusively established partnerships with top research universities worldwide, including member institutions of the elite UK Russell Group of research-intensive universities. The Ministry of Education also requires that the “curriculum, learning outcomes, and degrees awarded meet home campus standards,” as stated in a recent study of IBCs in four Asian countries, which included those in China. The results of these measures seem to be positive. That same study found that “learning outcomes assessment and measures [at IBCs in China] were usually the same as the home campus, in order to assist graduates to be highly competitive in [the] global job market.”

Partnership Model: Developing Domestic Capacity

The key to China’s protective policy is the requirement that all providers of TNE, including IBCs, partner with a local organization. This requirement leaves room for the establishment of a wide range of TNE arrangements, including joint programs, articulation agreements, and distance education. Some of these TNE arrangements, known as “joint venture institutions,” are classified as IBCs by C-BERT. Joint venture institutions are autonomous legal entities owned and operated in partnership between a Chinese and a foreign higher education provider. China’s Ministry of Education refers to them as China-Foreign Cooperation in Running Schools (CFCRS) institutions. Successful completion of study at a CFCRS institution typically leads to the awarding of two degrees—one from the foreign partner institution, and one from the independent CFCRS institution. The degree awarded by the foreign institution to IBC graduates is identical to that awarded to students studying at the institution’s main campus. The degree awarded by the China-based CFCRS institution is identical to a standard Chinese “diploma of graduation.” The degrees awarded in each country are recognized by the relevant domestic accrediting agencies.

CFCRS institutions are subject to many of the same regulations pertaining to China’s rapidly growing private higher education sector. Government regulation of tuition fees, which must be reviewed and approved by the relevant local bureaus, is among the most consequential for foreign institutions intent on establishing branches in China. While this regulation in theory sets a ceiling on the amount IBCs can charge, in practice, IBCs and TNE programs are often given permission to charge fees that are higher than their local counterparts.

Partnership Ideal

The operating ideal of these joint venture institutions is that of a partnership of equals. The 2004 CFCRS implementation measures mentioned above stipulate that “Chinese and foreign cooperators who intend to carry out Chinese-foreign cooperative education shall enter into cooperative agreements on the basis of equality and negotiation.” In practice, this ideal translates into greater participation on the part of host country actors—whether institutional or governmental—than what is seen in many other IBCs throughout the world. For example, according to QAA’s 2012 Review of UK Transnational Education in China, the Ministry of Education’s CFCRS policy encourages both the “merging of Chinese and foreign courses” and the collaborative development of new courses by both partner institutions, as opposed to the wholesale replication of the foreign institution’s curriculum.

The partnership model is not without its critics. The requirement that foreign education providers partner with domestic Chinese institutions was among the barriers to trade which the U.S. requested be removed in the early stages of the Doha round of GATS negotiations. Furthermore, the practice of awarding dual degrees for the completion of a single course of study has long been a source of controversy throughout the world, with critics alleging that it effectively double counts academic work and may consequentially dilute the perceived value of all academic degrees.

Course Offerings as a Reflection of National Priorities

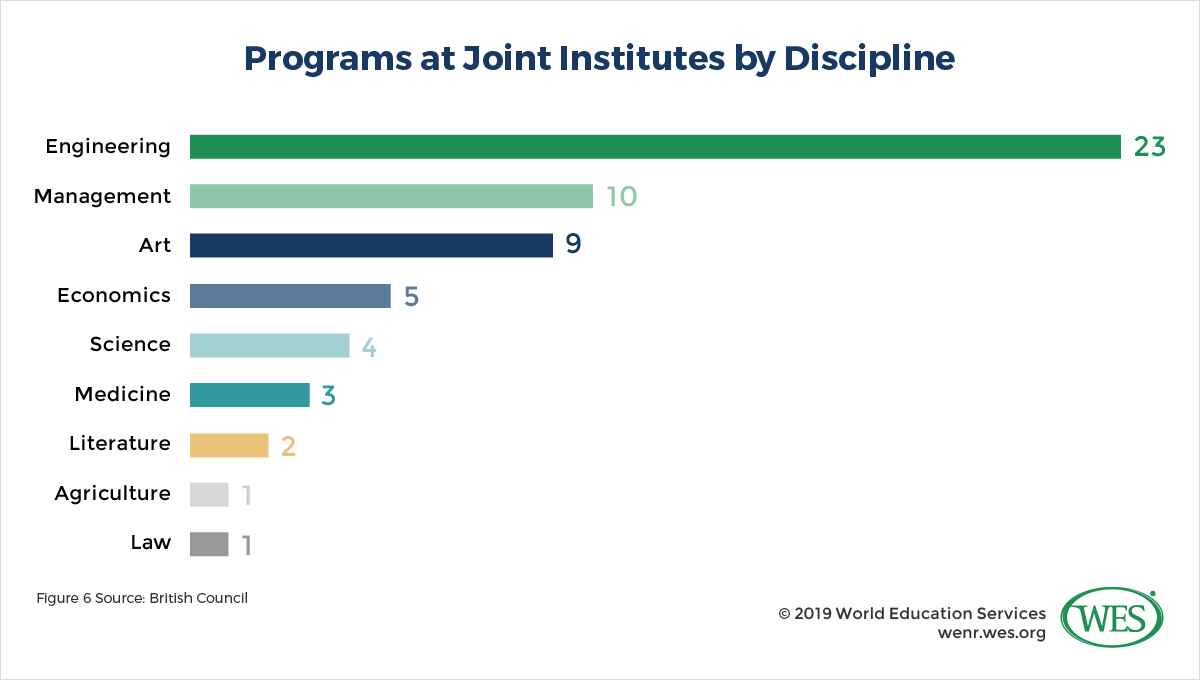

When considering approval of CFCRS institutions or programs, the Ministry of Education favors subject areas of especial importance to provincial and national development needs, while discouraging the establishment of programs in oversaturated subject areas, such as business and management. The results of that guidance are visible in the relative prevalence of different subjects taught at China’s IBCs. According to a 2017 British Council report of 17 UK joint institutes4 operating in China, engineering was the most commonly offered subject. Business programs, such as management and economics, which were by far the most popular subjects offered in the UAE’s IBCs, made up only a quarter of the total in China (see Figure 6).

The University of Nottingham Ningbo China (UNNC)’s decision to open the Centre for Sustainable Energy Technologies (CSET) further exemplifies this emphasis on subject areas of relevance to national and provincial needs. Established in 2008, CSET seeks to research “new and renewable energy systems and components for both domestic (housing) and non-domestic (commercial and public) buildings.” This field is vitally important to China’s long-booming construction industry and renewable energy priorities.

Student Recruitment and Brain Drain

Unlike in the UAE, local students predominate at China’s IBCs. The study of IBCs in four Asian countries mentioned previously also found that local students far outnumber international students in China’s IBCs. It cites an example of one IBC where more than 90 percent of enrolled students were Chinese citizens. The preponderance of local students in IBCs largely reflects China’s migration context as a whole, which still sees rural to urban internal migration sufficient to support its fast-growing, city-based economy. This trend is not likely to last forever, as China’s aging population and increased regional integration have already begun to reverse its long-standing negative net migration rate.

However, just as many Chinese civilians are moving from the countryside to the cities in search of better employment opportunities, many Chinese students are moving overseas in search of better educational opportunities—and the greater earning potential foreign credentials promise. In fact, Chinese students currently account for 17 percent of all international students, with 399,155 (46 percent) of them enrolled in the U.S. or UK. More significant still, many Chinese students who study internationally in developing countries choose not to return home after graduation. For example, 83 percent of Chinese international students receiving doctoral degrees from a U.S. institution in 2017 indicated that they intended to remain in the U.S. after completing their studies. The establishment of branch campuses is intended to put a dent in that outbound mobility and stem China’s brain drain to the West.

Conclusion—China

China’s desire to develop its domestic higher education capacity and quality in a direction best suited to fulfill its wide-ranging political and economic ambitions has shaped both the form and rapid growth of China’s IBCs. An exception for international universities written into China’s new foreign NGO law illustrates the circumstances under which China views IBCs and TNE partnerships as beneficial to the country’s interests. The exceptions or “carve outs” exempt foreign universities from the law’s most draconian demands only to the extent that the universities are engaged in activities of “exchange and cooperation” with their Chinese partners. As pointed out above, this protectionist attitude has resulted in various barriers to market access and a movement toward ever tighter domestic oversight of institution and program quality.

It is important to point out that this protectionist attitude and the resulting restrictions placed on IBCs do not appear to have diminished the appeal of the Chinese market to foreign institutions. The advantages of establishing an academic presence in the world’s largest higher education market, and the benefit of partnering with institutions in a country increasingly willing and able to invest in advanced research are reasons enough for many institutions to forgo some aspects of institutional autonomy.

Conclusion

As mentioned in our previous article, reaching a consensus on the definition of IBC has proved difficult. That difficulty reflects the variety of forms IBCs have taken throughout the world, as the examples of IBCs in the UAE and China illustrate. That diversity also extends to the motivations of the host institution. A number of considerations—the most prominent of which are revenue, reputation, and academics—drive HEIs to look beyond the borders of their home country for new markets. But the most significant cause of IBC variety can be found in the host country, whose regulatory environment—fiscal, academic, or otherwise—plays a leading role in shaping the structure of IBCs within its borders. Molding these regulations are the host country’s political, economic, and social realities and objectives, all of which are inseparable from increasing globalization.

That globalization will continue seems certain—whether its promised benefits will be spread evenly across the world remains an open question. However, in the case of IBCs, global change is already under way. Countries throughout the world, from Indonesia and Vietnam to Egypt and Saudi Arabia, are taking a second look at branch campuses, and crafting legislation to ease their entry through their borders. Others, like China, long a net importer of IBCs, are planning to export their own.

Competition can be a spur to innovation—among its inventions are many of the communications and transportation technologies that have made IBCs possible. But competition can also spur imitation, as the global spread of goods and ideas as varied as reality TV shows and Western higher education systems illustrates. With competition for internationally mobile students and institutions intensifying globally, IBCs will need to incorporate both innovation and imitation into their institutional strategies. Success in this competitive market will require an awareness of the many successful examples of IBCs throughout the world.

It will also demand an awareness of the circumstances in which they thrived. Such an understanding not only allows institutions to pick and choose the most fruitful features of earlier IBCs, it also provides the contextual information necessary for an honest evaluation of the viability of their own plans. A comprehensive understanding of past successes and failures also lays a solid foundation for the success of future innovations, which will undoubtedly arise as home and host institutions and societies continue to look for ways to fully realize the promise of transnational education.

1. Despite the UAE’s reliance on foreign labor, its naturalization requirements are prohibitively restrictive, permitting applications for citizenship only from Arabic-speaking expats who have resided in the UAE for at least 30 years.

2. Emphasis added.

3. According to Michael Gow, a senior research fellow at the University of Nottingham’s China Policy Institute quoted in the article, only 104 programs were closed between 2016 and 2018, 125 between 2006 and 2015.

4. Note that C-BERT recognizes only eight UK IBCs operating in China, and 32 total Chinese IBCs, while the Chinese Ministry of Education recognizes 70 joint institutions. Under C-BERT’s definition of IBCs, all IBCs are joint institutions, while not all MoE-recognized joint institutions are IBCs.