Better Career Services for International Students = Better Retention and Recruitment

Bryce Loo, Research Associate, WES

Career prospects are a top concern for international students studying at U.S. colleges and universities. A 2015 WES report on how master’s students choose U.S. institutions found that career prospects are, overall, the top factor that sway graduate students toward one institution instead of another. A second report produced by NAFSA and WES, Bridging the Gap, cited access to career opportunities as one of the biggest areas of dissatisfaction for undergraduate international students at U.S. higher education institutions. The report explored “what we think we know about the reasons international undergraduates enroll at a particular campus, why they stay, or why they transfer.” Good career services emerged as the third most cited practice by students for institutions to have in place in order to help international students.

Taken together, these findings highlight a troubling disconnect between international students and the higher education institutions that host them: On the one hand, career prospects are a major pull factor for international students who come to the U.S. On the other, the career services available are often a significant disappointment.

Understanding Barriers, Identifying Remedies

In 2016, WES conducted exploratory research into practices at institutions that provide strong career services to international students. Our objective was twofold: to understand the barriers that thwart international students from obtaining work, and to document established and effective practices at effective institutions.

Our research was conducted in three phases and involved multiple types of sources: a review of the literature; an exploratory survey of institutional officers with firsthand knowledge of providing career services to international students; and interviews with select career services officers who rated their office’s efforts as ‘very effective’.

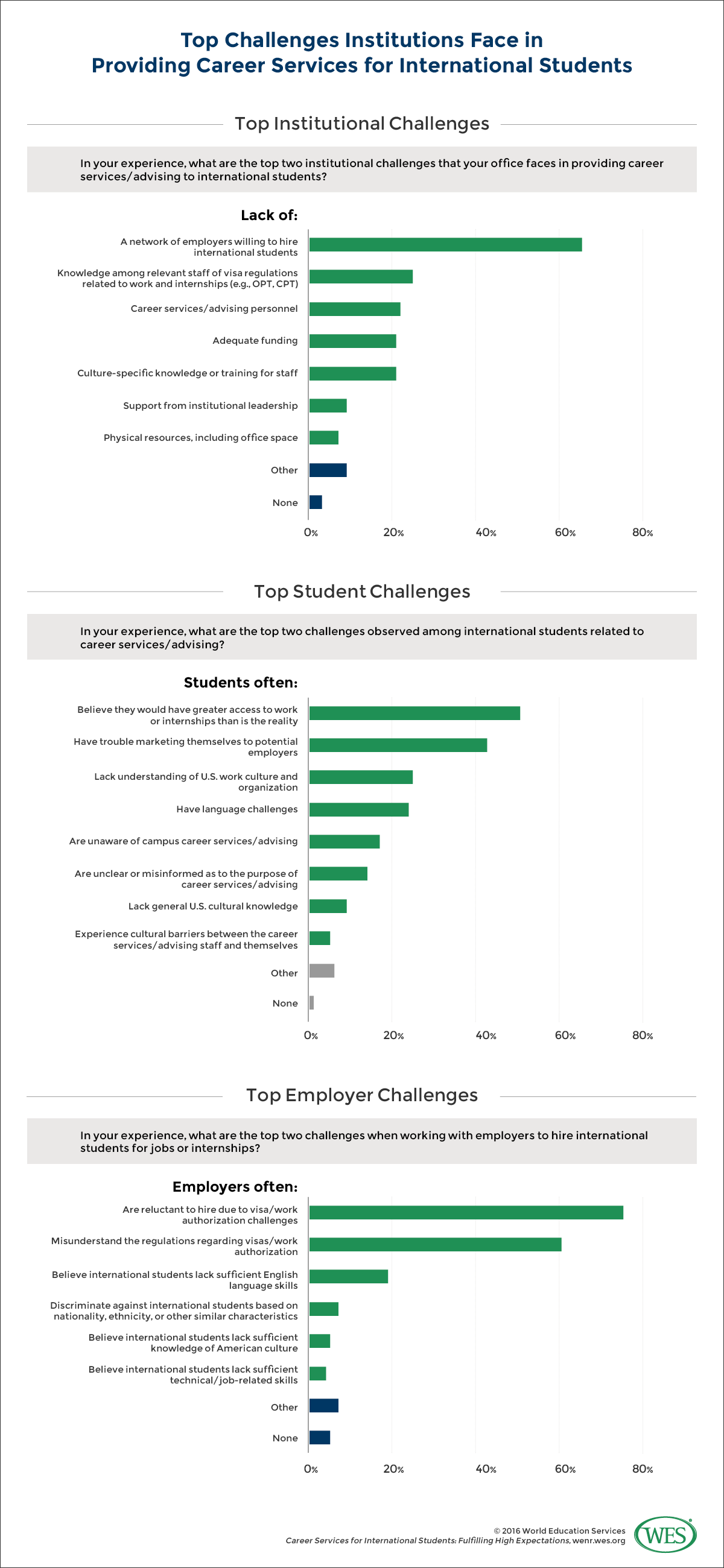

Overall, we discovered barriers specific to institutions, barriers specific to employers, and barriers specific to students. For instance, 85 percent of institutions cited failure to have an established network of employers to turn to as a major challenge. Familiarity with relevant visa regulations was also a significant barrier for both institutions and employers. Students, meanwhile, suffered from an array of challenges including overblown employment expectations, linguistic skills, and culturally loaded challenges around marketing themselves and their skills to American employers.

International Student Visas: A Quick Primer

Employers, career services professionals and volunteers, and international students all benefit from a basic understanding of the visa programs that enable foreign students to work in the U.S. Short-term work authorization options include:

- The Curricular Practical Training (CPT) Program covers F-1 students seeking work or internship related to their field of study during coursework. CPT participants may work either part-time (usually during the school year) or full-time (usually during the summer.) After 12 months of full-time CPT, the student is not eligible for OPT.

- The Optional Practical Training (OPT) Program covers F-1 students pursuing part- or full-time work, paid or unpaid, related to the field of study for 12 months immediately after the end of their program.

- The STEM Extension for OPT applies to F-1 students in certain STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) fields can receive a 24-month extension of the 12-month OPT, for a total of 36 months.

- Academic Training (AT) Programs apply to J-1 students working or interning in positions related to their fields of study. AT programs apply during or immediately after program completion. The length of AT depends on the length of the program of study. During coursework, students can work less than 20 hours a week, but following end of coursework, students must work at least 20 hours a week.

Longer-term work authorization options include:

- H1-B visas are temporary, three-year work authorization permits for employees with employer sponsorship. They are renewable for a three-year extension. There is an annual quota on H1-B visas; however, employees of some organizations such as nonprofits, and research and educational institutions are exempt.

Source: University of California, Berkeley

Effective Practices are Intentional and Strategic

What we learned about how ‘effective’ institutions approach these challenges is that they are intentional and strategic. These institutions tend to know (and to work to address) the needs and challenges of international students at a level that extends far beyond predictable issues such as visa requirements. They are adept at identifying the ways in which international students’ career services needs are both similar to and different from those of domestic students, and savvy about communicating across departments and channels to reach international students with the right information at the right time.

Importantly, they are also savvy about working with potential employers off campus, both to break down common misconceptions about the challenges of hiring international students and to create durable and informed networks of employers to whom they can refer their job-seeking international students.

Effective institutions typically adopted at least some of the following strategies, each of which can be adapted by other institutions seeking to better address international students’ career and employment prospects:

- They engage a network of external employers willing to hire international students: Institutions seeking to improve career services for international students should develop a reliable network of potential employers, educate them on perceived barriers such as work authorization, and develop networks of those willing to hire international students.

- They understand and address international students’ distinctive needs: Beyond visa issues, most international students have job-related needs – for instance, language skills and culturally specific resume writing skills – that domestic students do not. Institutions should determine how best to address those needs, whether through additional services or a discrete international career services group.

- They educate students early: Our research indicates that a large factor in dissatisfaction with career services may stem from misplaced expectations about how readily available job opportunities may be once students arrive on campus. Outreach early in the recruitment process can help set expectations and maintain student satisfaction. Effective institutions also provide international students with career training and education almost as soon as they arrive on campus, with a particular focus on how to communicate with potential employers about work authorization.

- They help students to develop soft skills: Our research indicated that opportunities to obtain culturally appropriate soft skills were available through low-pressure, on-campus jobs and internships. Participation in job fairs can also help international students hone their communication and networking skills, while also offering employers the chance to observe students’ potential merits first-hand.

- They help students who return home once their studies in the U.S. are complete: Many international students do not stay in the U.S. beyond OPT or Academic Training, and some may even return home immediately. Effective institutions consider these possibilities and develop practices for helping students to network and find employment pathways back home or in other countries.

- They ensure cross-institutional communication among relevant administrative offices: Multiple administrators have insight into the barriers that may prevent international students from making their first inroads into professional environments. Regular meetings between the Career Services and International Student Services and others facilitate communication, collaboration and better outcomes for students.

- They use the right channels to communicate with students: Social media has created new ways to reach a large number of students cost effectively. Our research indicates that effective institutions have begun to rely on these channels to provide students with career services information, concentrating on those where students tend to congregate and disregarding others.

Student Choices, Student Benefits

International students have become increasingly important to U.S. colleges and universities, particularly as funding has dwindled and domestic enrollment has declined. In order to continue attracting international students over the long term (rather than just getting the next year’s crop through the door), institutions need to be mindful of the multiple factors – including career aspirations – that lead students to select one institution over another. International students need to leave knowing that the cost of their education will pay dividends in terms of their careers. It is not an area that can simply be left to chance.

Detailed findings, and an overview of participants in the survey and interviews are available in the full version of the report, available for download here.